Contents

- 1. Translating “I miss you” directly

- 2. Saying “ma amie” instead of “mon amie”

- 3. Mixing up rencontrer and retrouver

- 4. Using pour to describe periods of time

- 5. Confusing c’est and il/elle est

- 6. Using penser de instead of penser à

- 7. Misplacing adjectives

- 8. Using visiter to talk about paying someone a visit

- 9. Using attendre for “to attend”

- 10. Saying c’est chaud and c’est froid for the weather

- 11. Using the verb être (to be) to talk about age

- 12. Using the incorrect prepositions with countries

- 13. Mixing gender agreement between nouns and articles

- And One More Thing...

13 Common French Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

No one likes to get caught in an embarrassing language blunder. Mixing up words that sound alike, confusing your tenses, losing your accent…we’ve all been there!

Although there’s no need to panic if this happens, familiarizing yourself with some of the most common mistakes can help you perfect your French and avoid social awkwardness. Check out these 13 common mistakes made by French learners so you can avoid them and speak French more confidently.

We also cover some of these mistakes in the FluentU French YouTube video below:

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

1. Translating “I miss you” directly

The verb manquer (to miss) uses a different sentence construction in French, and saying “Je te manque” actually means “you miss me” rather than “I miss you.”

To our English-language minds, manquer messes with the word order in a sentence. It switches around the subject and the speaker. If you want to say “I miss you” in French, you would say “Tu me manques.”

While getting to grips with the word order can be difficult, there’s an easy way to remember this: “Tu me manques” can be translated as “You are missing to me,” which puts the speaker and the subject in the correct positions.

2. Saying “ma amie” instead of “mon amie”

To describe a male friend in French, you might say “mon ami” (my friend). It would therefore make sense to use the feminine possessive adjective ma (my) when describing a female friend, but that’s not the case.

In order to flow when spoken aloud, feminine nouns that start with a vowel actually take the masculine possessive adjective (mon) to avoid running two vowel sounds together.

So to talk about a female friend (amie), you would say “mon amie,” running the final consonant sound into the first vowel. The masculine possessive mon creates a liaison between the words when they’re spoken aloud.

Learn more about French gender rules here.

3. Mixing up rencontrer and retrouver

The verb rencontrer (to meet) might seem simple enough, but in fact, it’s used only in very specific circumstances. While you might be tempted to use it in all examples of “meetings,” it specifically describes bumping into someone on the street, meeting someone by chance or meeting them for the first time.

If you want to talk about meeting up with your friends on purpose, then you must use the verb retrouver (to find).

Think of it like this: when you make your way out to meet your friends, you must find them in the crowd and pinpoint their location. Reunited, you can have your meeting or appointment!

4. Using pour to describe periods of time

In English, we typically describe periods of time using the word “for.” For example, we’ll say “I’ve lived here for five years.” But in French, we use the word pendant (during) to describe periods of time, rather than pour (for). For example:

J’ai étudié le français pendant six mois. (I studied French for six months.)

While pendant can be used to describe the majority of time frames, there’s one crucial anomaly: If you want to refer to a future time frame, you can use pour. For example:

Je pars pour trois semaines. (I’m leaving for three weeks.)

Learn more about this common mistake in the video below:

5. Confusing c’est and il/elle est

Both c’est and il est or elle est can be used to say “it is” or “he/she is,” but are applied in very different circumstances.

Typically, c’est can be used in the following two situations:

- Before masculine adjectives to describe general conditions (how something looks or feels). For example: “C’est beau ici” (It’s beautiful here).

- Before articles like un (a/an) or le (the). For example: “C’est un bon professeur de français” (He’s a good French teacher) or “C’est une bonne amie à moi” (She’s a good friend to me).

On the other hand, il and elle can be used when there’s no article in the sentence. For example: “Elle est belle” (She’s beautiful) or “Il est en panne” (It’s broken).

6. Using penser de instead of penser à

Saying that you’re thinking about someone in French can be a really touching thing to do, but unless you get your grammar right, you could be making a big mistake.

While in English, we would say “I’m thinking of you,” the French language doesn’t work in the same way. In order to express the same sentiment, you would need to say “Je pense à toi” (Literally: I’m thinking at you).

On the other hand, if you wish to ask what somebody thinks about you, you can ask, “Qu’est-ce que tu penses de moi?” (What do you think of me?)

7. Misplacing adjectives

One of the first things we learn in French is that unlike in English, French adjectives go after the nouns they modify. While this is mostly true, there are a number of French adjectives that appear before the noun they modify.

The most common adjectives that come before the noun are:

Bon

— good

Mauvais

— bad

Petit

— small

Grand

— big

Joli

— pretty

To describe a pretty girl, for example, you would say “la jolie fille.”

While these are exceptions rather than the rule, it’s important to remember which adjectives come before a noun. As soon as you see one in a text, or hear one spoken out loud, try to make a note of it and remember it for the future.

8. Using visiter to talk about paying someone a visit

Visiter can only be used in specific circumstances, such as when you’re visiting a place or attraction, rather than a person.

While you might be tempted to say “Je vais visiter ma grand-mère” for “I’m going to visit my grandma,” this is incorrect.

Instead, you should use rendre visit à (to pay a visit to) when talking about visiting a person. For example:

Je vais rendre visite à ma grand-mère. (I’m going to visit my grandma.)

9. Using attendre for “to attend”

While it might sound similar to the English word, in French, attendre is actually a false friend that means “to wait.” Faux amis, or false friends, are words that look like a word in English but actually have completely different meanings.

If you want to say that you attended something, you must use the verb assister. For example:

“J’ai assisté à une conférence sur le changement climatique à Pairs. (I attended a conference on climate change in Paris.)

Confusing false friends is common among French learners, and there are many to look out for, such as monnaie (change), librairie (bookshop) and coin (corner). You’ll pick up on the majority of these over time, so don’t worry if you make a mistake earlier on!

10. Saying c’est chaud and c’est froid for the weather

Another common mistake happens when describing the weather in French. Many learners will try to translate the phrases “It’s hot” or “It’s cold” literally, saying “C’est chaud” and “C’est froid” to talk about the temperature outside.

This is incorrect. To say it’s hot or cold out in French, we use “il fait.” So “It’s hot” is “Il fait chaud” and “It’s cold” is “Il fait froid.”

Although French people will be able to understand what you’re saying either way, learning differences like these at an early stage can really pay off and make the language much easier down the line.

11. Using the verb être (to be) to talk about age

This common mistake stems from a larger mistake that many English speakers learning French often make. That is, trying to translate from English to French.

Direct translations from English to French work from time to time, but more often than not, they can end up sounding clunky or sometimes just plain incorrect to French natives.

For example, while French and English use the verbs avoir (to have) and être (to be) in many similar cases, there are some that differ.

One common mixup happens when talking about age. You can say “I’m 30 years old” in English. But in French, you would say “J’ai 30 ans” (Literally: I have 30 years).

12. Using the incorrect prepositions with countries

French learners often mistakenly use the preposition à with countries. However, you should generally use the prepositions en, au, or aux, depending on the gender and singular/plural form of the country’s name:

- En: Use en with feminine countries or those that begin with a vowel sound. For example: “J’habite en France” (I live in France).

- Au: Use au with masculine countries that don’t begin with a vowel sound. For example: “Il voyage au Canada” (He’s traveling to Canada).

- Aux: Use aux with plural countries, regardless of gender. For example: “Ils vont aux États-Unis” (They’re going to the United States).

13. Mixing gender agreement between nouns and articles

French differs greatly from English in its use of gendered nouns and articles, which means that many mistakes are made in this area. For that reason, it deserves its own section and a bit longer of an explanation.

The masculine indefinite article un (a/an) is used before masculine nouns while the feminine indefinite une (a/an) presents feminine nouns. For example:

• un livre

(a book)

• une pomme

(an apple)

In addition, possessive adjectives like “my,” “your” and “his/her” have a gender that must agree with the nouns they modify. In the masculine form, these are written as mon/ton/son (my/your/his), and in the feminine form as ma/ta/sa (my/your/her).

The masculine, feminine and plural forms of nouns are most easily detected when they’re written down. Take the noun “cousin,” for example:

• mon cousin

— my (male) cousin

• ma cousine

— my (female) cousin

• mes cousins

— my cousins

These rules generally apply to most French nouns and articles, but there are some exceptions, as we saw in #2 on the list with mon amie.

Usually, when a feminine word starts with a vowel, it will take the masculine article or adjective to avoid the clash of vowel sounds. For example, un heure (an hour) is a feminine noun preceded by a masculine article.

Making a mistake in French might seem like the end of the world, but when it comes to your comprehension, it can be incredibly useful.

Embarrassing conversational blunders can stick with us for much longer than the best French lessons, reminding us to pay attention to specific parts of the language.

So while taking note of the above will definitely help you get your French right, it’s also important to remember that everyone slips up from time to time.

The best thing is to correct yourself, pick yourself back up and get back on that language-learning road!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you like learning French at your own pace and from the comfort of your device, I have to tell you about FluentU.

FluentU makes it easier (and way more fun) to learn French by making real content like movies and series accessible to learners. You can check out FluentU's curated video library, or bring our learning tools directly to Netflix or YouTube with the FluentU Chrome extension.

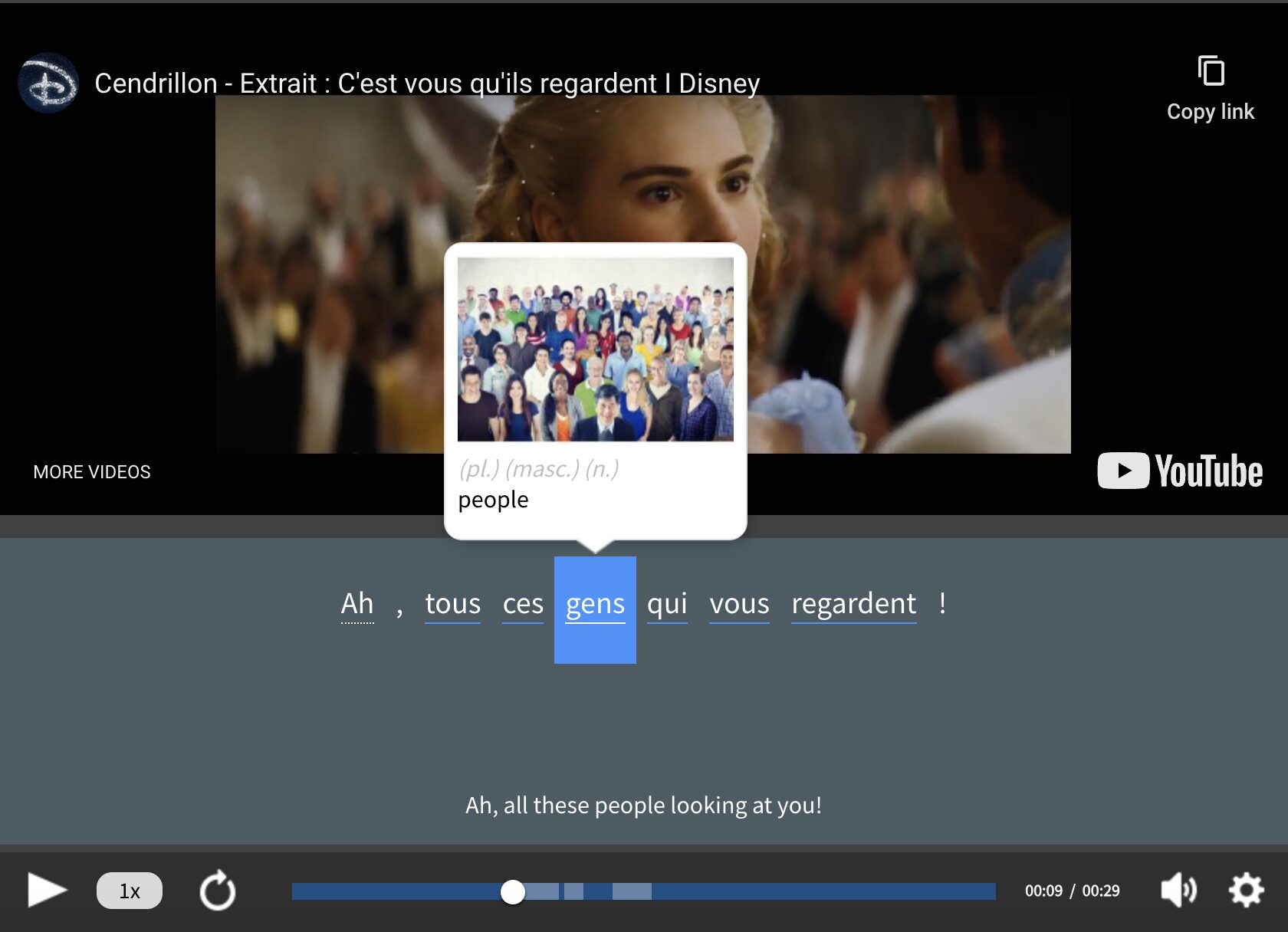

One of the features I find most helpful is the interactive captions—you can tap on any word to see its meaning, an image, pronunciation, and other examples from different contexts. It’s a great way to pick up French vocab without having to pause and look things up separately.

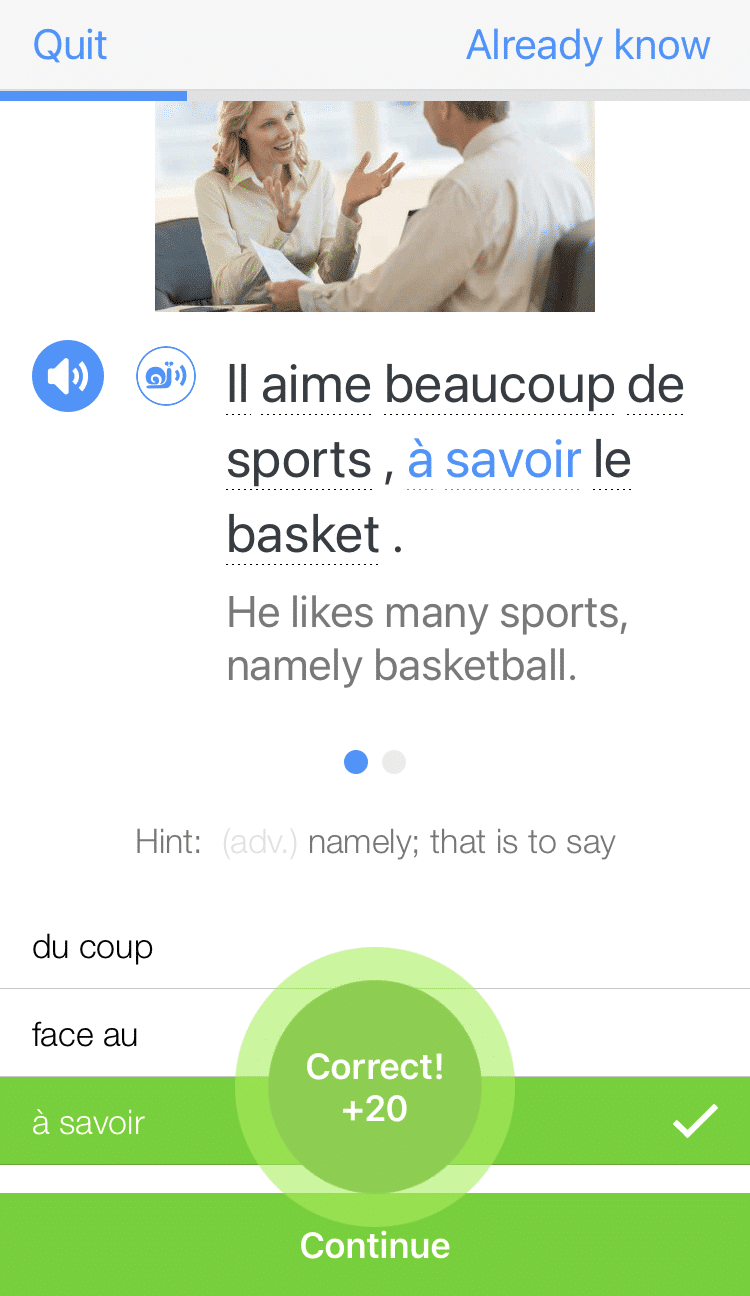

FluentU also helps reinforce what you’ve learned with personalized quizzes. You can swipe through extra examples and complete engaging exercises that adapt to your progress. You'll get extra practice with the words you find more challenging and even be reminded you when it’s time to review!

You can use FluentU on your computer, tablet, or phone with our app for Apple or Android devices. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)