The Dr. And Mrs. Vandertramp Verbs for Using “Avoir” or “Être”

One of the trickiest—but most important—exceptions in French grammar involves the verbs that pair with être instead of avoir in the passé composé. These are commonly remembered using the mnemonic “Dr. and Mrs. Vandertramp,” a tool designed to make an essential grammar rule more accessible.

We’ll break down this mnemonic, explain its quirks and share memory strategies to help you conquer this aspect of French grammar.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Are Vandertramp Verbs

First off, let’s get one thing straight: if you ask any French person about Vandertramp verbs, they’ll probably look at you quite quizzically.

The Dr. Mrs. Vandertramp mnemonic is used exclusively by foreign language learners to remember an essential French grammar exception. But to understand the exception, you must first understand the rule.

Dr. Mrs. Vandertramp verbs apply to the passé composé , a French verb tense used to talk about the past.

As its name (which translates to “composed past”) suggests, the passé composé is made up of two parts: the auxiliary verb and the past participle of the lexical verb.

Too much grammar-ese? Let’s break it down further.

The auxiliary verb is also sometimes known as the “helping” verb in English. It’s a verb that doesn’t have any lexical meaning but rather performs a grammatical function. In the case of the passé composé, its presence lets the listener know that the verb phrase is in the past. The lexical verb, on the other hand, is the verb that brings actual meaning to the sentence.

For example:

J’ai parlé avec ma mère. (I spoke with my mother.)

In this sentence, the auxiliary verb is avoir (to have)—the one conjugated in the simple present tense. The lexical verb is parler (to speak) and the past participle of the lexical verb ( parlé ) is used.

Past Participle Overview

Past participles generally follow a simple rule. For verbs ending in -er, -ir and -re, the past participle is made by adding the suffix -é, -i and -u to the root, respectively.

For example:

| French Verbs | Past Participle Form |

|---|---|

| parler (to speak) | parlé (spoken) |

| dessiner (to draw) | dessiné (drawn) |

| tomber (to fall) | tombé (fallen) |

| choisir (to choose) | choisi (chosen) |

| finir (to finish) | fini (finished) |

| pâlir (to become pale) | pâli (paled) |

| descendre (to go down) | descendu (went down) |

| rendre (to return) | rendu (returned) |

| fendre (to split) | fendu (split) |

There are, of course, exceptions to this. Here are a few of the most common irregular past participles:

| French Verbs | Irregular Past Participle Form |

|---|---|

| devoir (to have to) | dû (should) |

| avoir (to have) | eu (had) |

| pouvoir (to be able to) | pu (could) |

| faire (to do/make) | fait (did) |

| savoir (to know) | su (known) |

| connaître (to know) | connu (known) |

| voir (to see) | vu (seen) |

| boire (to drink) | bu (drank) |

| vouloir (to want) | voulu (wanted) |

Auxiliary Verbs

In most cases, the auxiliary verb used in the passé composé is avoir. The verb is conjugated in the present according to the subject pronoun being used. However, in certain exceptional cases être (to be) is used—and that’s where our friends the Vandertramps come in.

Dr. Mrs. Vandertramp as a Mnemonic Device

Dr. Mrs. Vandertramp is a mnemonic device used to remember which verbs are conjugated with être as opposed to avoir in the passé composé. These are the verbs associated with the mnemonic:

| Dr. Mrs. Vandertramp Verbs | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Devenir | to become |

| Revenir | to come back |

| Monter | to go up |

| Retourner | to return |

| Sortir | to go out |

| Venir | to come |

| Aller | to go |

| Naître | to be born |

| Descendre | to go down |

| Entrer | to enter |

| Rentrer | to go home/to return |

| Tomber | to fall |

| Rester | to remain |

| Arriver | to arrive |

| Mourir | to die |

| Partir | to leave |

A lot of these verbs are similar in meaning. This video from our YouTube channel should help clear up any confusion between some of the verbs.

For many, the easiest way to learn these verbs is to simply memorize the phrase, filling each verb in next to the appropriate letter and using the mnemonic as a guide.

However, there are other ways to memorize these verbs that you may prefer.

The House Mnemonic

This is a different mnemonic device used to remember the Dr. Mrs. Vandertramp verbs that involves drawing a house. Draw a house with a door, stairs and windows, then label it with the être verbs. This becomes a circuit.

First, someone arrives at the house (arriver). He has come (venir) to the house. Then he enters (entrer) the house and goes up the stairs (monter). Then he goes downstairs (descendre). Then he returns upstairs (retourner) and falls down the stairs (tomber). He remains in the house for a bit (rester) before deciding to leave (partir). He tries the door, but sees that it’s locked, so he goes out (sortir) the window. And then he goes (aller) on his way.

This mnemonic also includes one verb that doesn’t feature in the Vandertramp mnemonic, passer par (pass by).

When passer (to pass) is used without the preposition par (by), it uses avoir. However, when par is added, passer takes être, and the same is true with other prepositions.

For example:

| Passer With Avoir | Passer With Être |

|---|---|

| J’ai passé un bon moment hier soir. (I had a good time last night.) | Je suis passé par la petite rue derrière chez toi. (I passed by/via the little road behind your house.) |

| J’ai passé la compote de pommes dans une passoire. (I passed the applesauce through a strainer.) | Je suis passé devant la bibliothèque. (I passed by the library.) |

| J’ai passé le pain à Hervé. (I passed the bread to Hervé.) | Je suis passé au supermarché. (I went to the supermarket.) |

While the mnemonic doesn’t include all of the prepositions, passer par or passer devant is easily inserted into the house circuit (for example, passer devant by the window or passer par in the kitchen). This makes it easy to remember that every time passer is used with a preposition, it becomes one of the members of the house verbs.

With this mnemonic, the derivatives (devenir, revenir, rentrer) as well as the beginning and end-of-life verbs (naître, mourir) must be memorized and remembered separately. This is the mnemonic preferred by most French mother tongue learners, as it’s a very visual way of learning.

Exceptions to the Vandertramp Rule

It wouldn’t be a French grammar rule without a few exceptions. You’ll see certain Dr. Mrs. Vandertramp verbs used with the auxiliary avoir, and this is not necessarily a mistake—a change in auxiliary can reflect a change in the meaning of the verb.

For example, even though sortir is a Vandertramp verb, you can see the sentence J’ai sorti les poubelles , meaning “I took out the trash.”

Here are a few other such examples:

J’ai monté les courses jusqu’au troisième étage. (I carried the groceries up to the third floor.)

J’ai retourné mon T-shirt. (I turned my T-shirt inside out.)

J’ai sorti le chien. (I took the dog outside.)

J’ai descendu les bouteilles au recyclage. (I took the bottles down to the recycling bin.)

J’ai rentré les données dans le tableau. (I entered the data into the table.)

The reason for these exceptions is a bit complex—you may just want to remember that when the Vandertramp verbs are transitive (i.e., they take a direct object), they are conjugated in the past with avoir instead of être.

Exercise Bank

Of course, the best way to get a handle on these somewhat tricky verbs is to try them out. Here are some of our favorite exercises using the Vandertramp verbs:

- Dr. Mrs. Vandertramp verbs quiz

- A short passé composé quiz

- Avoir or être? A short quiz

- An exercise bank of 7 exercises

- Exercises 17-22 on this page are about the passé composé

Memorizing the Dr. Mrs. Vandertramp Verbs

The handy memory tricks above make Vandertramp verbs a lot easier to remember. But to really stick these verbs in your brain, you should try to immerse yourself in the language as much as possible. This will get you accustomed to all aspects of French and make you internalize all the rules so they come to you more automatically.

This can be done with all kinds of media over the internet or with language learning programs such as FluentU.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

And be aware—these mnemonics aren’t just useful for the passé composé.

Any composed tense, from the plus-que-parfait (pluperfect) to the past conditional, will use the same rule.

Might as well get it mastered now!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you like learning French at your own pace and from the comfort of your device, I have to tell you about FluentU.

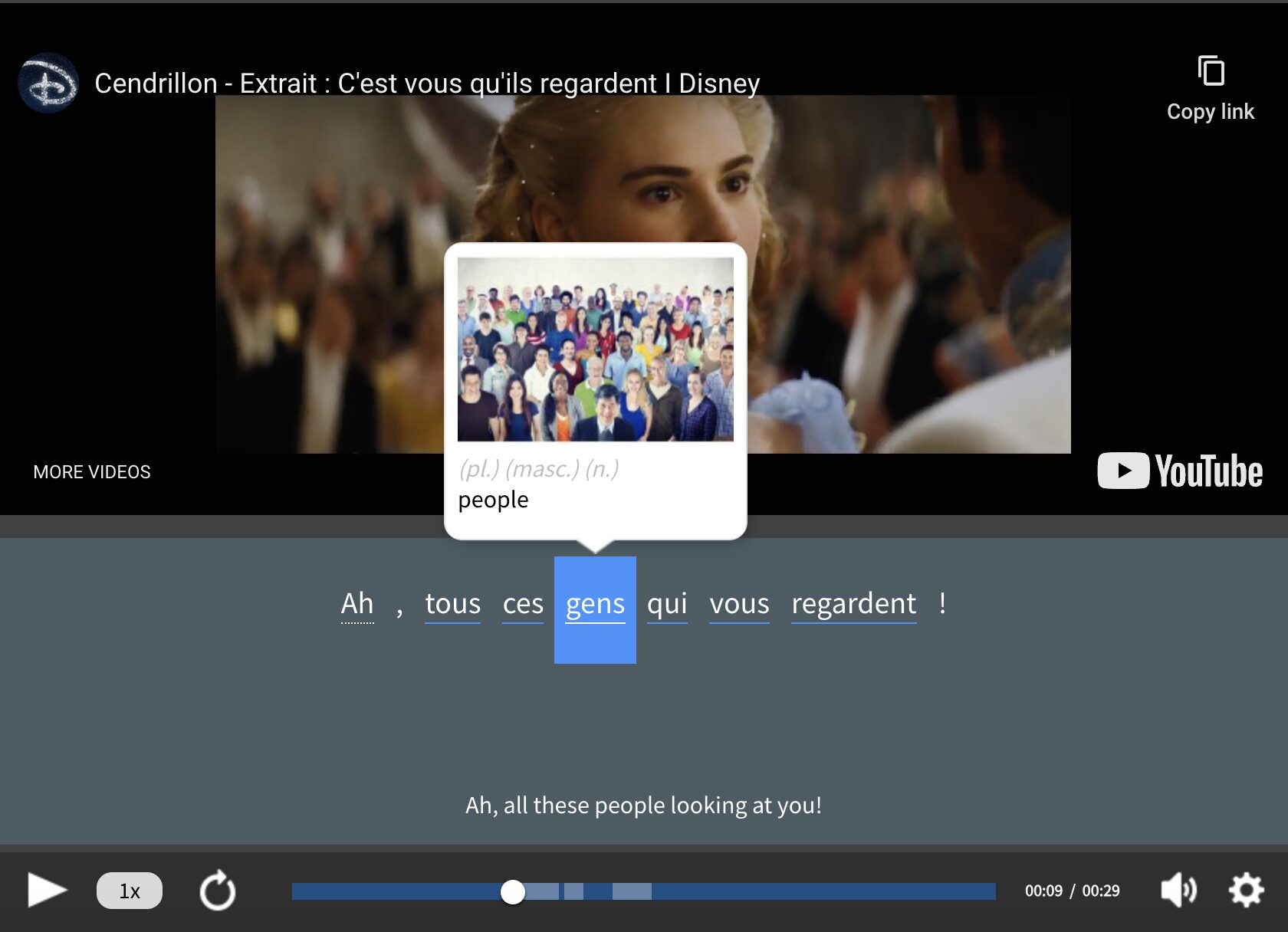

FluentU makes it easier (and way more fun) to learn French by making real content like movies and series accessible to learners. You can check out FluentU's curated video library, or bring our learning tools directly to Netflix or YouTube with the FluentU Chrome extension.

One of the features I find most helpful is the interactive captions—you can tap on any word to see its meaning, an image, pronunciation, and other examples from different contexts. It’s a great way to pick up French vocab without having to pause and look things up separately.

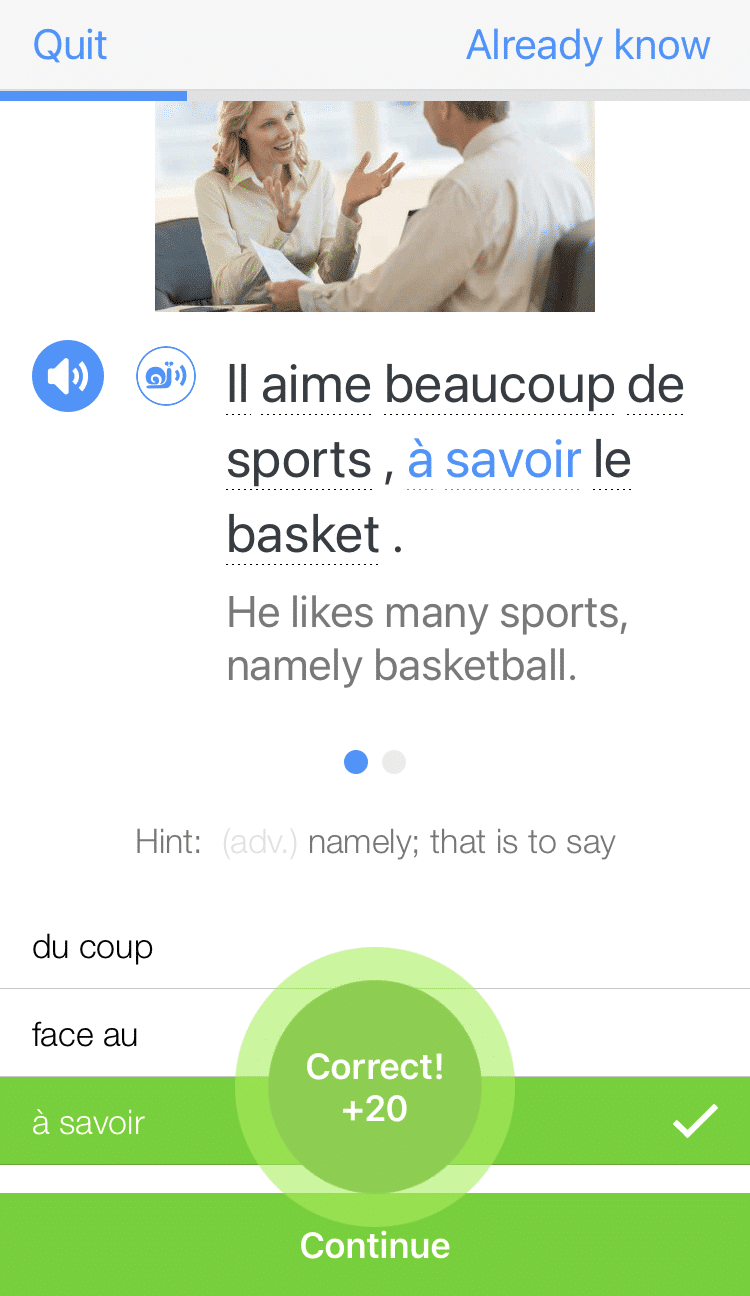

FluentU also helps reinforce what you’ve learned with personalized quizzes. You can swipe through extra examples and complete engaging exercises that adapt to your progress. You'll get extra practice with the words you find more challenging and even be reminded you when it’s time to review!

You can use FluentU on your computer, tablet, or phone with our app for Apple or Android devices. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)