How to Write an Essay in French

When it comes to expressing your thoughts in French, there’s nothing better than the essay. It is, after all, the favorite form of such famed French thinkers as Montaigne, Chateaubriand, Houellebecq and Simone de Beauvoir.

In this post, I’ve outlined the four most common types of essays in French, ranked from easiest to most difficult, to help you get to know this concept better.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Must-have French Phrases for Writing Essays

Before we get to the four main types of essays, here are a few French phrases that will be especially helpful as you delve into essay-writing in French:

Introductory phrases, which help you present new ideas.

| French | English |

|---|---|

| tout d'abord | firstly |

| premièrement | firstly |

Connecting phrases, which help you connect ideas and sections.

| French | English |

|---|---|

| et | and |

| de plus | in addition |

| également | also |

| ensuite | next |

| deuxièmement | secondly |

| or | so |

| ainsi que | as well as |

| lorsque | when, while |

Contrasting phrases, which help you juxtapose two ideas.

| French | English |

|---|---|

| en revanche | on the other hand |

| pourtant | however |

| néanmoins | meanwhile, however |

Concluding phrases, which help you to introduce your conclusion.

| French | English |

|---|---|

| enfin | finally |

| finalement | finally |

| pour conclure | to conclude |

| en conclusion | in conclusion |

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Types of French Essays and How to Write Them

1. Text Summary (Synthèse de texte)

The text summary or synthèse de texte is one of the easiest French writing exercises to get a handle on. It essentially involves reading a text and then summarizing it in an established number of words, while repeating no phrases that are in the original text. No analysis is called for.

A synthèse de texte should follow the same format as the text that is being synthesized. The arguments should be presented in the same way, and no major element of the original text should be left out of the synthèse.

Here is an informative post about writing a synthèse de texte, written for French speakers.

The text summary is a great exercise for exploring the following French language elements:

- Synonyms, as you will need to find other words to describe what is said in the original text.

- Nominalization, which involves turning verbs into nouns and generally cuts down on word count.

- Vocabulary, as the knowledge of more exact terms will allow you to avoid periphrases and cut down on word count.

While beginners may wish to work with only one text, advanced learners can synthesize as many as three texts in one text summary.

Since a text summary is simple in its essence, it’s a great writing exercise that can accompany you through your entire learning process.

2. Text Commentary (Commentaire de texte)

A text commentary or commentaire de texte is the first writing exercise where the student is asked to present an analysis of the materials at hand, not just a summary.

That said, a commentaire de texte is not a reaction piece. It involves a very delicate balance of summary and opinion, the latter of which must be presented as impersonally as possible. This can be done either by using the third person (on) or the general first person plural (nous). The singular first person (je) should never be used in a commentaire de texte.

A commentaire de texte should be written in three parts:

- An introduction, where the text is presented.

- An argument, where the text is analyzed.

- A conclusion, where the analysis is summarized and elevated.

Here is a handy in-depth guide to writing a successful commentaire de texte, written for French speakers.

Unlike with the synthesis, you will not be able to address all elements of a text in a commentary. You should not summarize the text in a commentary, at least not for the sake of summarizing. Every element of the text that you speak about in your commentary must be analyzed.

To successfully analyze a text, you will need to brush up on your figurative language. Here are some great resources to get you started:

- This guide to figurative language presents the different elements in useful categories.

- This guide, intended for high school students preparing for the BAC—the exam all French high school students take, which they’re required to pass to go to university—is great for seeing examples of how to integrate figurative language into your commentaries.

- Speaking of which, here’s an example of a corrected commentary from the BAC, which will help you not only include figurative language but get a head start on writing your own commentaries.

3. Dialectic Dissertation (Thèse, Antithèse, Synthèse)

The French answer to the 5-paragraph essay is known as the dissertation. Like the American 5-paragraph essay, it has an introduction, body paragraphs and a conclusion. The stream of logic, however, is distinct.

There are actually two kinds of dissertation, each of which has its own rules.

The first form of dissertation is the dialectic dissertation, better known as thèse, antithèse, synthèse. In this form, there are actually only two body paragraphs. After the introduction, a thesis is posited. Following the thesis, its opposite, the antithesis, is explored (and hopefully, debunked). The final paragraph, what we know as the conclusion, is the synthesis, which addresses the strengths of the thesis, the strengths and weaknesses of the antithesis, and concludes with the reasons why the original thesis is correct.

For example, imagine that the question was, “Are computers useful to the development of the human brain?” You could begin with a section showing the ways in which computers are useful for the progression of our common intelligence—doing long calculations, creating in-depth models, etc.

Then you would delve into the problems that computers pose to human intelligence, citing examples of the ways in which spelling proficiency has decreased since the invention of spell check, for example. Finally, you would synthesize this information and conclude that the “pro” outweighs the “con.”

The key to success with this format is developing an outline before writing. The thesis must be established, with examples, and the antithesis must be supported as well. When all of the information has been organized in the outline, the writing can begin, supported by the tools you have learned from your mastery of the synthesis and commentary.

Here are a few tools to help you get writing:

- Here’s an example of a plan for a dialectic dissertation, showing you the three parts of the essay as well as things to consider when writing a dialectic dissertation.

4. Progressive Dissertation (Plan progressif)

The progressive dissertation is slightly less common, but no less useful, than the first form.

The progressive form basically consists of examining an idea via multiple points of view—a sort of deepening of the understanding of the notion, starting with a superficial perspective and ending with a deep and profound analysis.

If the dialectic dissertation is like a scale, weighing pros and cons of an idea, the progressive dissertation is like peeling an onion, uncovering more and more layers as you get to the deeper crux of the idea.

Concretely, this means that you will generally follow this layout:

- A first, elementary exploration of the idea.

- A second, more philosophical exploration of the idea.

- A third, more transcendent exploration of the idea.

This format for the dissertation is more commonly used for essays that are written in response to a philosophical question, for example, “What is a person?” or “What is justice?”

Let’s say the question was, “What is war?” In the first part, you would explore dictionary definitions—a basic idea of war, i.e. an armed conflict between two parties, usually nations. You could give examples that back up this definition, and you could narrow down the definition of the subject as much as needed. For example, you might want to make mention that not all conflicts are wars, or you might want to explore whether the “War on Terror” is a war.

In the second part, you would explore a more philosophical look at the topic, using a definition that you provide. You first explain how you plan to analyze the subject, and then you do so. In French, this is known as poser une problématique (establishing a thesis question), and it usually is done by first writing out a question and then exploring it using examples: “Is war a reflection of the base predilection of humans for violence?”

In the third part, you will take a step back and explore this question from a distance, taking the time to construct a natural conclusion and answer for the question.

This form may not be as useful in as many cases as the first type of essay, but it’s a good form to learn, particularly for those interested in philosophy. Here’s an in-depth guide to writing a progressive dissertation.

Why Are French Essays Different?

Writing an essay in French is not the same as those typical 5-paragraph essays you’ve probably written in English.

In fact, there’s a whole other logic that has to be used to ensure that your essay meets French format standards and structure. It’s not merely writing your ideas in another language.

And that’s because the French use Cartesian logic (also known as Cartesian doubt), developed by René Descartes, which requires a writer to begin with what is known and then lead the reader through to the logical conclusion: a paragraph that contains the thesis. Through the essay, the writer will reject all that is not certain or all that is subjective in his or her quest to find the objective truth.

As you progress in French and become more and more comfortable with writing, try your hand at each of these types of writing exercises, and even with other forms of the dissertation. You’ll soon be a pro at everything from a synthèse de texte to a dissertation!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you like learning French at your own pace and from the comfort of your device, I have to tell you about FluentU.

FluentU makes it easier (and way more fun) to learn French by making real content like movies and series accessible to learners. You can check out FluentU's curated video library, or bring our learning tools directly to Netflix or YouTube with the FluentU Chrome extension.

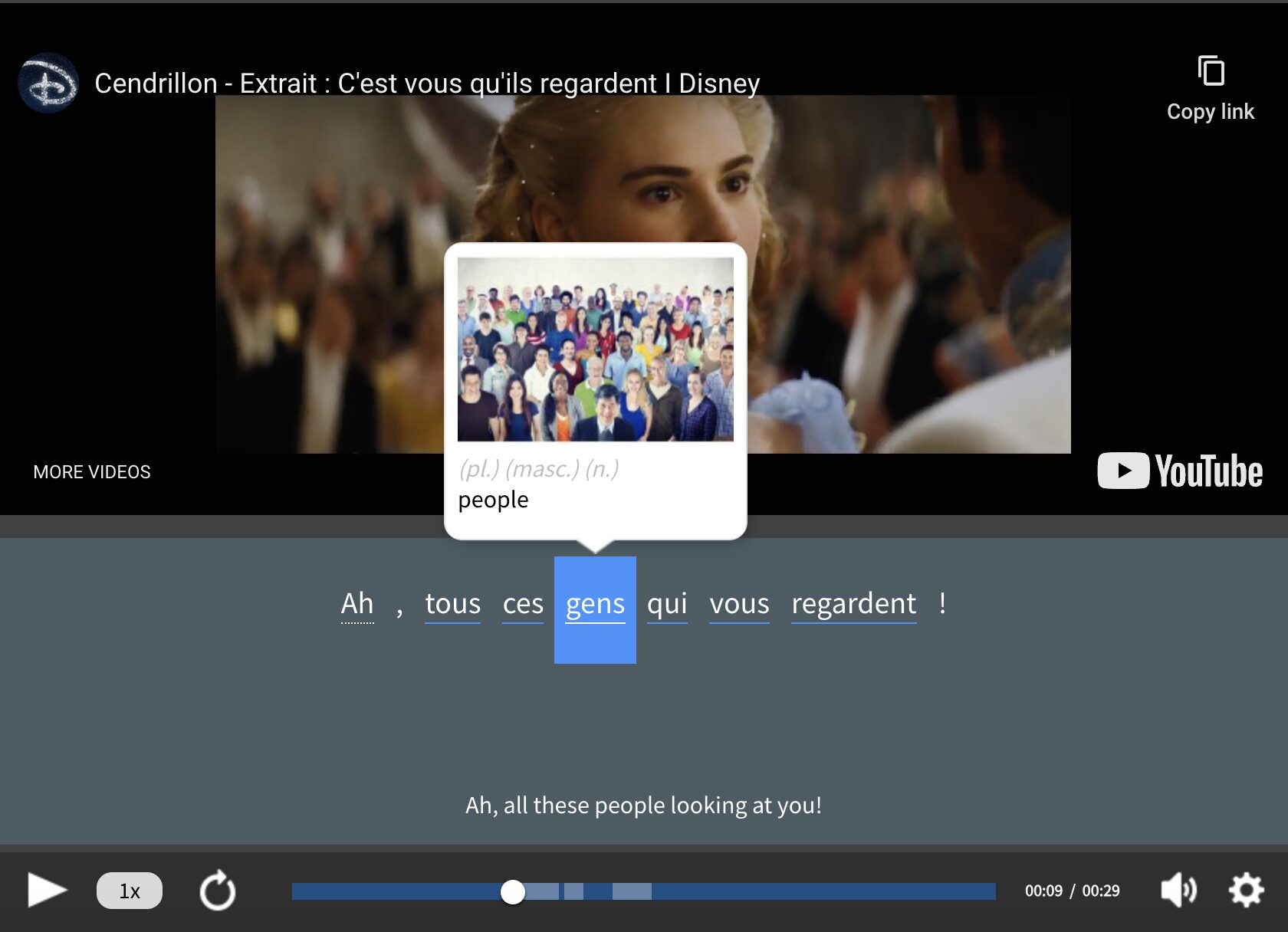

One of the features I find most helpful is the interactive captions—you can tap on any word to see its meaning, an image, pronunciation, and other examples from different contexts. It’s a great way to pick up French vocab without having to pause and look things up separately.

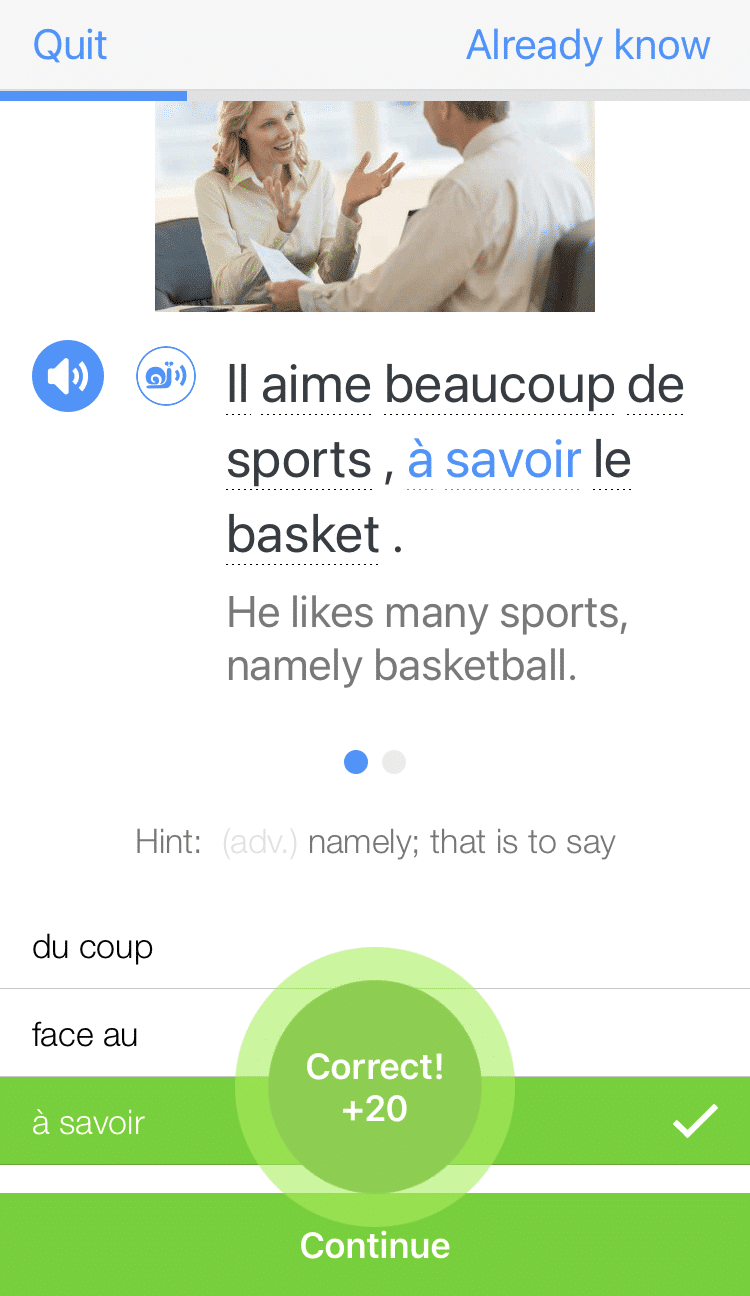

FluentU also helps reinforce what you’ve learned with personalized quizzes. You can swipe through extra examples and complete engaging exercises that adapt to your progress. You'll get extra practice with the words you find more challenging and even be reminded you when it’s time to review!

You can use FluentU on your computer, tablet, or phone with our app for Apple or Android devices. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)