Contents

- “Non sono in queste rive” by Torquato Tasso

- “Parola” by Ribka Sibhatu

- “Rimani” by Gabriele D’Annunzio

- “L’infinito” by Giacomo Leopardi

- “Ho bisogno di sentimenti” by Alda Merini

- “Se questo è un uomo” by Primo Levi

- “Non so” by Antonia Pozzi

- “Ho sceso, dandoti il braccio” by Eugenio Montale

- “All’anima mia” by Umberto Saba

- “San Martino” by Giosuè Carducci

- “Il lampo” by Giovanni Pascoli

- “Divina Commedia” by Dante Alighieri

- “Ed è subito sera” by Salvatore Quasimodo

- “Soldati” by Giuseppe Ungaretti

- Bonus Poem: “Sonetto” by Cecco Angiolieri

- Tips for Using Italian Poems in Your Program

- And One More Thing...

15 Beautiful Italian Poems for Language Learners

Poems add a new dimension to learning a language, and they can make it much easier to remember key vocabulary. Not to mention, Italian poems are amazing—we’re talking about the language of love, after all.

In this blog post, we’ll show you 15 Italian poems that you must absolutely check out, plus some useful tips for incorporating them into your language program.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

“Non sono in queste rive” by Torquato Tasso

This poem, written by a brilliant Renaissance poet, is a tale of love. Learners are given an opportunity to see how basic vocabulary can be used to create something truly beautiful. Notice the way the poet compares the beauty of the poem’s subject to nature!

Non sono in queste rive

fiori così vermigli

come le labbra de la donna mia,

né ’l suon de l’aure estive

tra fonti e rose e gigli

fa del suo canto più dolce armonia.

Canto che m’ardi e piaci,

t’interrompano solo i nostri baci.

English Translation: “Are Not in These Shores”

Are not in these shores

crimson flowers

like the lips of my lady,

in the sound of the summer breeze

amidst fountains, and roses and lilies

does its song make the sweetest harmony.

Song that inflames, and pleases me,

may you be interrupted only by our kisses.

“Parola” by Ribka Sibhatu

“Parola” (word) is a perfect representation of modern poetry. In both Italian and English, readers can clearly see and feel the words that empower and give substance to the mystery of women everywhere.

Sacra Parola,

misteriosa essenza,

terra della straniera

che girovaga!

Tocca la figlia che

cammina tra

luci e ombra,

coraggio e paura.

Suona melodie

che danno forma

al mondo

a cui appartiene.

Parla parole ce

emanano profumo

e portano l’animo

nel tempo e nello spazio.

English Translation (by André Naffis-Sahely): “Word”

Holy word

inscrutable essence

land of the wandering

woman!

Touch the daughter

who walks between

shadow and light

courage and fear.

Play melodies

that give shape

to the world

where she belongs.

Speak words

that emit a fragrance

and carry the soul

through time and through space.

“Rimani” by Gabriele D’Annunzio

Gabriele D’Annunzio was a poet, playwright and journalist who had a flair for writing romance. His poem “Stay” is a love story for the ages. In the poem, a couple begs each other not to leave, be fearful or restless. It’s a pledge to guard and watch over another, lovingly and faithfully.

Rimani! Riposati accanto a me.

Non te ne andare.

Io ti veglierò. Io ti proteggerò.

Ti pentirai di tutto fuorché d’essere venuta a me, liberamente, fieramente.

Ti amo. Non ho nessun pensiero che non sia tuo;

non ho nel sangue nessun desiderio che non sia per te.

Lo sai. Non vedo nella mia vita altra compagna, non vedo altra gioia.

Rimani.

Riposati. Non temere di nulla.

Dormi stanotte sul mio cuore…

English Translation: “Stay”

Stay! Rest beside me.

Do not go.

I will watch you. I will protect you.

You’ll regret anything but coming to me, freely, proudly.

I love you. I do not have any thought that is not yours;

I have no desire in the blood that is not for you.

You know. I do not see in my life another companion, I see no other joy

Stay.

Rest. Do not be afraid of anything.

Sleep tonight on my heart…

“L’infinito” by Giacomo Leopardi

Many have loved this poem for its apparent simplicity and basic vocabulary, but the message certainly isn’t simple. This poem speaks to the depths of humanity and the shared feelings of all. It’s a great poem for pronunciation practice, as the words slip off the tongue effortlessly!

Sempre caro mi fu quest’ermo colle,

E questa siepe, che da tanta parte

Dell’ultimo orizzonte il guardo esclude.

Ma sedendo e mirando, interminati

Spazi di là da quella, e sovrumani

Silenzi, e profondissima quiete

Io nel pensier mi fingo; ove per poco

Il cor non si spaura. E come il vento

Odo stormir tra queste piante, io quello

Infinito silenzio a questa voce

Vo comparando: e mi sovvien l’eterno,

E le morte stagioni, e la presente

E viva, e il suon di lei. Così tra questa

Immensità s’annega il pensier mio:

E il naufragar m’è dolce in questo mare.

English Translation: “Infinity”

Always dear to me was this still hill,

And this hedge, which in so many ways

Of the last horizon the look excludes.

But sitting and aiming, endless

Spaces beyond that, and superhuman

Silences, and deepest quiet

I pretend in thinking; where for a while

The heart is not afraid. And like the wind

I hear rustling among these plants, I that

Infinite silence to this voice

I am comparing: and the eternal comes to my mind,

And the dead seasons, and the present

And alive, and the sound of her. So between this

Immensity drowns my thought:

And shipwreck is sweet to me in this sea.

“Ho bisogno di sentimenti” by Alda Merini

If you like poetry, then you’ll resonate with this beautiful poem, which talks about looking for emotional richness and spiritual fulfillment through art. Alda Merini is one of the more modern poets on this list and a Nobel Prize winner, and her poems tend to be passionate, with themes like love and mental illness.

Io non ho bisogno di denaro.

Ho bisogno di sentimenti.

Di parole, di parole scelte sapientemente,

di fiori, detti pensieri,

di rose, dette presenze,

di sogni, che abitino gli alberi,

di canzoni che faccian danzar le statue,

di stelle che mormorino all’orecchio degli amanti…

Ho bisogno di poesia,

questa magia che brucia la pesantezza delle parole,

che risveglia le emozioni e dà colori nuovi…

English Translation: “I Need Feelings”

I do not need money.

I need feelings,

words, words wisely chosen,

flowers called thoughts,

roses called presences,

dreams that inhabit the trees,

songs that make statues dance,

stars that murmur in lovers’ ears.

I need poetry,

this magic that burns away the heaviness of words.

“Se questo è un uomo” by Primo Levi

Primo Levi is best known for his books about the Holocaust since he experienced being a prisoner in a concentration camp. He even wrote memoirs about it, which made “Se questo è un uomo” (If this is a man) an iconic phrase and launched his literary career. His first memoir includes this haunting poem:

Voi che vivete sicuri

nelle vostre tiepide case,

voi che trovate tornando a sera

il cibo caldo e visi amici:

Considerate se questo è un uomo

che lavora nel fango

che non conosce pace

che lotta per mezzo pane

che muore per un si o per un no.

Considerate se questa è una donna,

senza capelli e senza nome

senza più forza di ricordare

vuoti gli occhi e freddo il grembo

come una rana d’inverno.

Meditate che questo è stato:

vi comando queste parole.

Scolpitele nel vostro cuore

stando in casa andando per via,

coricandovi, alzandovi.

Ripetetele ai vostri figli.

O vi si sfaccia la casa,

la malattia vi impedisca,

i vostri nati torcano il viso da voi.

English Translation (by Ruth Feldman and Brian Swan): “If This is a Man”

You who live secure

In your warm houses

Who return at evening to find

Hot food and friendly faces:

Consider whether this is a man,

Who labours in the mud

Who knows no peace

Who fights for a crust of bread

Who dies at a yes or a no.

Consider whether this is a woman,

Without hair or name

With no more strength to remember

Eyes empty and womb cold

As a frog in winter.

Consider that this has been:

I commend these words to you.

Engrave them on your hearts

When you are in your house, when you walk on your way,

When you go to bed, when you rise.

Repeat them to your children.

Or may your house crumble,

Disease render you powerless,

Your offspring avert their faces from you.

“Non so” by Antonia Pozzi

Antonia Pozzi only became famous for her poetry after her lifetime—in fact, her poems were all published after she died. Her poems often make references to nature, where she looked for solace and meaning when struggling with existential questions. The poem below uses nature imagery, like flowers, trees and gardens, to describe love:

Io penso che il tuo modo di sorridere

è più dolce del sole

su questo vaso di fiori

già un poco

appassiti —

penso che forse è buono

che cadano da me

tutti gli alberi —

ch’io sia un piazzale bianco deserto

alla tua voce — che forse

disegna i viali

per il nuovo

giardino.

English Translation (by Amy Newman): “I Don’t Know”

I think your way of smiling

is sweeter than the sun

on this vase of flowers

already a little

faded—

I think that maybe it’s good

that from me fall

all the trees—

That I be a white, deserted yard

to your voice—that maybe

draws the shady paths

for the new

garden.

“Ho sceso, dandoti il braccio” by Eugenio Montale

Eugenio Montale is considered one of the greatest Italian poets of the 20th century, and he was also a literary critic who wrote many essays. He dedicated this poem to his late wife, and it was quoted on social media when a famous football player died.

Ho sceso, dandoti il braccio, almeno un milione di scale

e ora che non ci sei è il vuoto ad ogni gradino.

Anche così è stato breve il nostro lungo viaggio.

Il mio dura tuttora, né più mi occorrono

le coincidenze, le prenotazioni,

le trappole, gli scorni di chi crede

che la realtà sia quella che si vede.

Ho sceso milioni di scale dandoti il braccio

non già perché con quattr’occhi forse si vede di più.

Con te le ho scese perché sapevo che di noi due

le sole vere pupille, sebbene tanto offuscate,

erano le tue.

English Translation: “I went down, arm in arm with you”

I went down a million stairs, at least, arm in arm with you.

And now that you are not here, I feel emptiness at each step.

Our long journey was brief, though.

Mine still lasts, but I don’t need

any more connections, reservations,

traps, humiliation of those who think reality

is what we are used to see.

I went down millions of stairs, at least, arm in arm with you,

and not because with four eyes we see better that with two.

With you I went downstairs because I knew, among the two of us,

the only real eyes, although very blurred,

belonged to you.

“All’anima mia” by Umberto Saba

If you’re a fan of soul-searching and introspection, this poem will appeal to you. Language learners can benefit from seeing how the poet formulates the questions driving the poem. The ending is extra special, showing that even darkness eventually gives way to sunshine and light.

Dell’inesausta tua miseria godi.

Tanto ti valga, anima mia, sapere;

sì che il tuo male, null’altro, ti giovi.

O forse avventurato è chi s’inganna?

né a se stesso scoprirsi ha in suo potere,

né mai la sua sentenza lo condanna?

Magnanima sei pure, anima nostra;

ma per quali non tuoi casi t’esalti,

sì che un bacio mentito indi ti prostra.

A me la mia miseria è un chiaro giorno

d’estate, quand’ogni aspetto dagli alti

luoghi discopro in ogni suo contorno.

Nulla m’è occulto; tutto è sì vicino

dove l’occhio o il pensiero mi conduce.

Triste ma soleggiato è il mio cammino;

e tutto in esso, fino l’ombra, è in luce.

English Translation: “To My Soul”

You delight in your unending misery.

Such, my soul, should be the worth of knowledge,

that your suffering alone should do you good.

Or is the self-deceived the lucky one?

He who cannot ever know himself

or the sentence of his condemnation?

Still, my soul, you are magnanimous;

yet how you thrill to phantom opportunities,

and so are brought down by a faithless kiss.

To me my misery is a bright summer

day, where from high up I can make out

every facet, every detail of the world below.

Nothing is obscure to me; it’s all right there,

wherever my eye or my mind leads me.

My road is sad but brightened by the sun;

and everything on it, even shadow, is in light.

“San Martino” by Giosuè Carducci

Giosuè Carducci was a poet and writer from the 19th century who won the Nobel Prize for Literature. His poem “San Martino” is very vividly written! Fun fact: St. Martin’s Day is actually a major day in Italy with lots of wine and festivals since it traditionally marks the end of the agricultural year.

La nebbia agli irti colli

piovigginando sale,

e sotto il maestrale

urla e biancheggia il mar;

ma per le vie del borgo

dal ribollir de’ tini

va l’aspro odor dei vini

l’anime a rallegrar.

Gira su’ ceppi accesi

lo spiedo scoppiettando:

sta il cacciator fischiando

su l’uscio a rimirar

tra le rossastre nubi

stormi d’uccelli neri,

com’esuli pensieri,

nel vespero migrar.

English Translation: “Saint Martin’s Day”

The fog to the bare hills

soars in the thin rain,

and below the wind

howls and churns the sea;

yet through the hamlet’s alleys

from the fermenting casks

goes the pungent scent of wines

to touch a soul with glee.

On the firewood, turns

the skewer crackling:

stands the hunter whistling,

on the threshold to see

in the reddening clouds

flocks of black birds,

like exiled thoughts

as in the dusk they flee.

“Il lampo” by Giovanni Pascoli

This striking poem describes a seemingly ordinary moment in nature with awe and mystery. Metaphorically, it’s also said to describe how Pascoli felt when he found out about his father’s death, who was suddenly shot by an assassin on the road. Another popular poem of his with a similar theme is “La cavalla storna.”

E cielo e terra si mostrò qual era:

la terra ansante, livida, in sussulto;

il cielo ingombro, tragico, disfatto:

bianca bianca nel tacito tumulto

una casa apparì sparì d’un tratto,

come un occhio, che, largo, esterrefatto,

s’aprì si chiuse, nella notte nera.

English Translation: “The Lightning”

And sky and earth showed what they were like:

the earth panting, livid, in a jolt;

the sky burdened, tragic, exhausted:

white, white in the silent tumult

a house appeared, disappeared in the blink of an eye;

like an eyeball that, enlarged, horrified,

opened and closed itself in the pitch-black night.

“Divina Commedia” by Dante Alighieri

One of the greatest Italian literary masterpieces and narrative poems of all time is Dante Alighieri’s “Divina Commedia,” which you’ve probably heard already! Written in the 14th century, it has three parts: “Inferno” (Hell), “Purgatorio” (Purgatory) and “Paradiso” (Paradise). Inferno is the most widely read—here’s a passage from the third canto that describes the gates of Hell:

Per me si va nella città dolente,

per me si va nell’etterno dolore,

per me si va tra la perduta gente.

Giustizia mosse il mio alto fattore:

fecemi la divina podestate,

la somma sapïenza e ‘l primo amore;

dinanzi a me non fuor cose create

se non etterne, e io etterno duro.

Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’intrate…

English Translation (by Allen Mandelbaum): “Inferno,” Canto III

Through me the way into the suffering city,

Through me the way to the eternal pain,

Through me the way that runs among the lost.

Justice urged on my high artificer;

My maker was divine authority,

The highest wisdom, and the primal love.

Before me nothing but eternal things

Were made, and I endure eternally.

Abandon every hope, who enter here.

“Ed è subito sera” by Salvatore Quasimodo

Salvatore Quasimodo was another Nobel Prize winner who was recognized for his lyrical poems. This poem of his might only have three lines, but it describes the entirety of human existence. To be human is to be alone, but life also has sunshine until it eventually ends.

Ognuno sta solo sul cuor della terra,

trafitto da un raggio di sole:

ed è subito sera.

English Translation (by Mike Towler): “And suddenly it is evening”

Everyone stands alone at the heart of the world

pierced by a ray of sunlight:

and suddenly it is evening.

“Soldati” by Giuseppe Ungaretti

Giuseppe Ungaretti is one of the most influential Italian poets of the 20th century, and he’s known for his minimalist style. Having lived through being a soldier in World War I, he came up with this poem about soldiers that’s well-known among Italians. Even if it only has four lines, it’s hauntingly beautiful:

Si sta come

D’autunno

sugli alberi

le foglie.

English Translation (by Greer Egan): “Soldiers”

We are

Autumnal

On the trees,

As the leaves.

Bonus Poem: “Sonetto” by Cecco Angiolieri

This early piece of Italian poetry speaks of disillusionment, despair and destruction. In many respects, it’s still a commentary that applies to some modern issues.

The poem includes Italian words that date back to the Middle Ages and are rarely used today. Because of this, it’s challenging for non-native speakers!

S’i’ fosse foco, ardere’ il mondo;

s’i’ fosse vento, lo tempesterei;

s’i’ fosse acqua, io l’ annegherei;

s’i’ fosse Dio, mandereil en profondo;

s’i’ fosse papa, sare’ allor giocondo,

ché tutti cristïani imbrigherei;

s’i’ fosse ’imperator, sa’ che farei?

a tutti taglierei lo capo a tondo.

S’i’ fosse morte, andarei da mio padre;

s’i’ fosse vita, fuggirei da lui;

similmente faría da mi’ madre.

S’ i’ fosse Cecco com’ i’ sono e fui,

torrei le donne giovani e leggiadre,

le vecchie e laide lasserei altrui.

English Translation (by Lorna de’ Lucchi): “Sonetto”

If I were fire, I’d burn the world;

if wind, around about it furiously I’d blow;

If water, drowning it would suit my mind;

If God, then I’d dispatch it straight below;

If I were pope, I’d have a bit of fun

By setting Christians one against another;

If emp’ror, well, what think ye I’d have done?

All heads chopped off, and so an end to bother!

I would go seek my father were I death;

But were I life from him I’d flee away;

And I’d behave the same towards my mother;

If Cecco, as I am and draw my breath,

I’d choose such ladies as are young and gay.

Leaving the old and ugly to another.

Tips for Using Italian Poems in Your Program

Thanks to their short verses, Italian poems can be faster to read and memorize compared to other materials. They’re also excellent resources for pronunciation practice, and reading the luxurious passages will make you feel like a real Roman.

Try putting these tips into practice:

- Power up your speaking skills by letting all of those incredible phrases roll off your tongue. You can also record yourself reading. Once finished, listen to the recording and check your pronunciation and accent.

- Make reading Italian poems a daily routine. Every bit of exposure to Italian ideas and culture increases your understanding of the language, and with the short poems above, reading one or two will take less than ten minutes.

- Look up new words and phrases. Since poetry is very sensory, you can get a deeper understanding of new vocabulary through FluentU’s multimedia Italian dictionary.

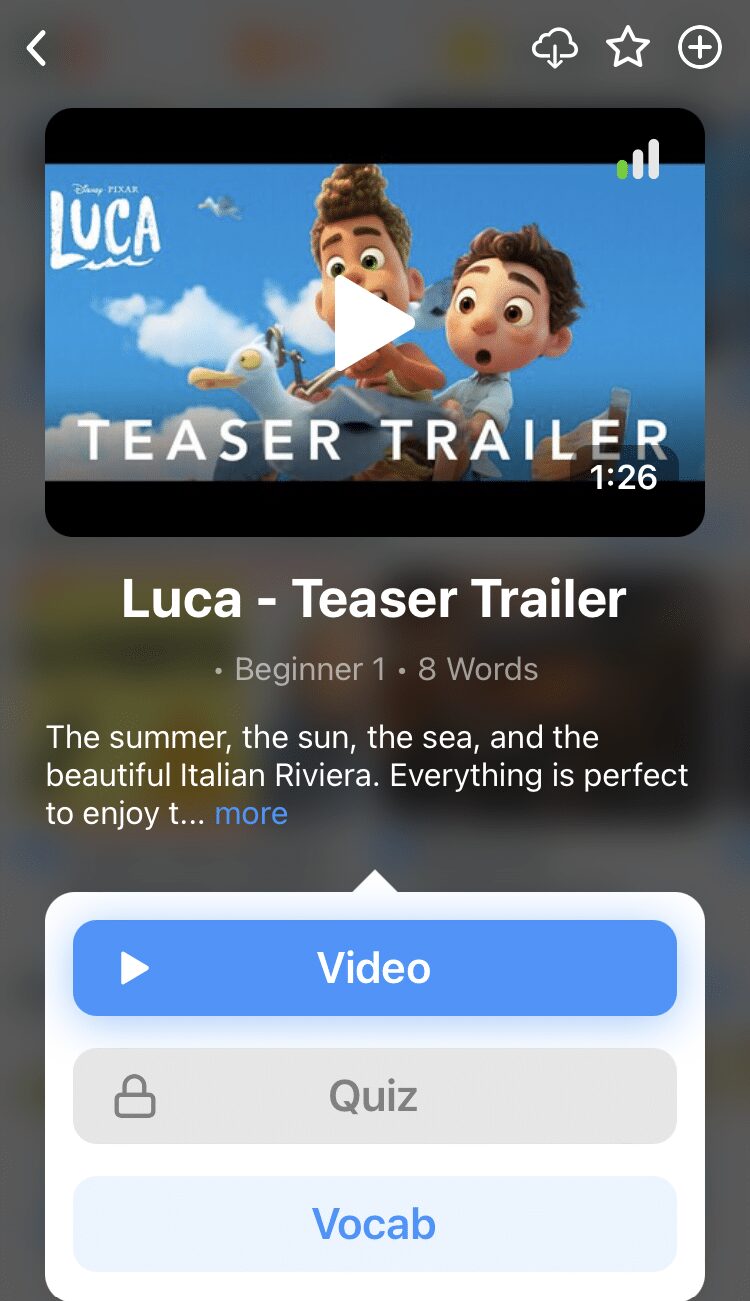

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

- If you’re a beginner (or just like learning with English translations), bilingual poetry books provide lots of learning potential. Seeing how each phrase translates into English not only teaches you colloquial phrases and idioms but also grammar structure.

Two high-quality bilingual poetry books to check out are “Introduction to Italian Poetry: A Dual-Language Book” and “The Selected Poetry of Pier Paolo Pasolini: A Bilingual Edition.”

Poetry showcases culture in a wonderful way. It offers a glimpse of love, life, history and what’s important to society. It’s a powerfully immersive experience that can power up your Italian skills with almost no effort at all.

Add poetry—the lyrics of life—to your Italian learning program to see the world through a native speaker’s eyes.

Enjoy, and have fun!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you're as busy as most of us, you don't always have time for lengthy language lessons. The solution? FluentU!

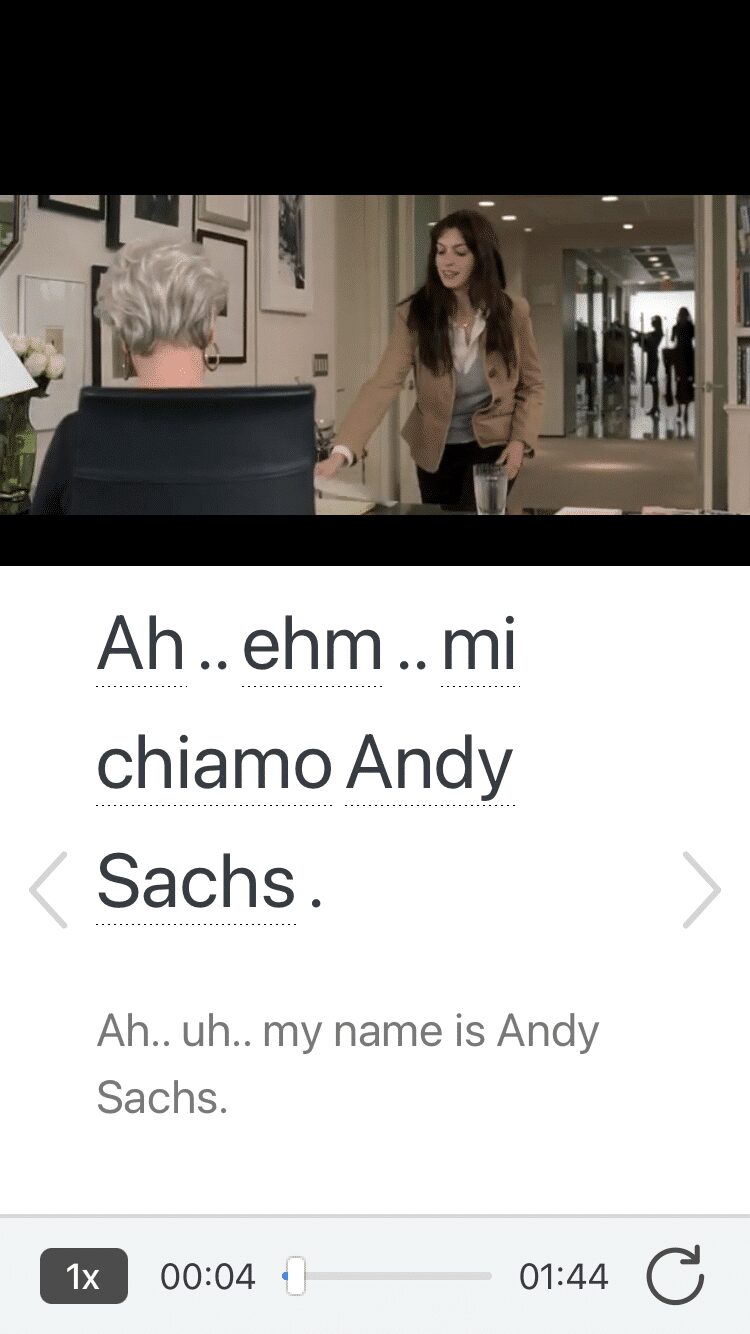

Learn Italian with funny commericals, documentary excerpts and web series, as you can see here:

FluentU helps you get comfortable with everyday Italian by combining all the benefits of complete immersion and native-level conversations with interactive subtitles. Tap on any word to instantly see an image, in-context definition, example sentences and other videos in which the word is used.

Access a complete interactive transcript of every video under the Dialogue tab, and review words and phrases with convenient audio clips under Vocab.

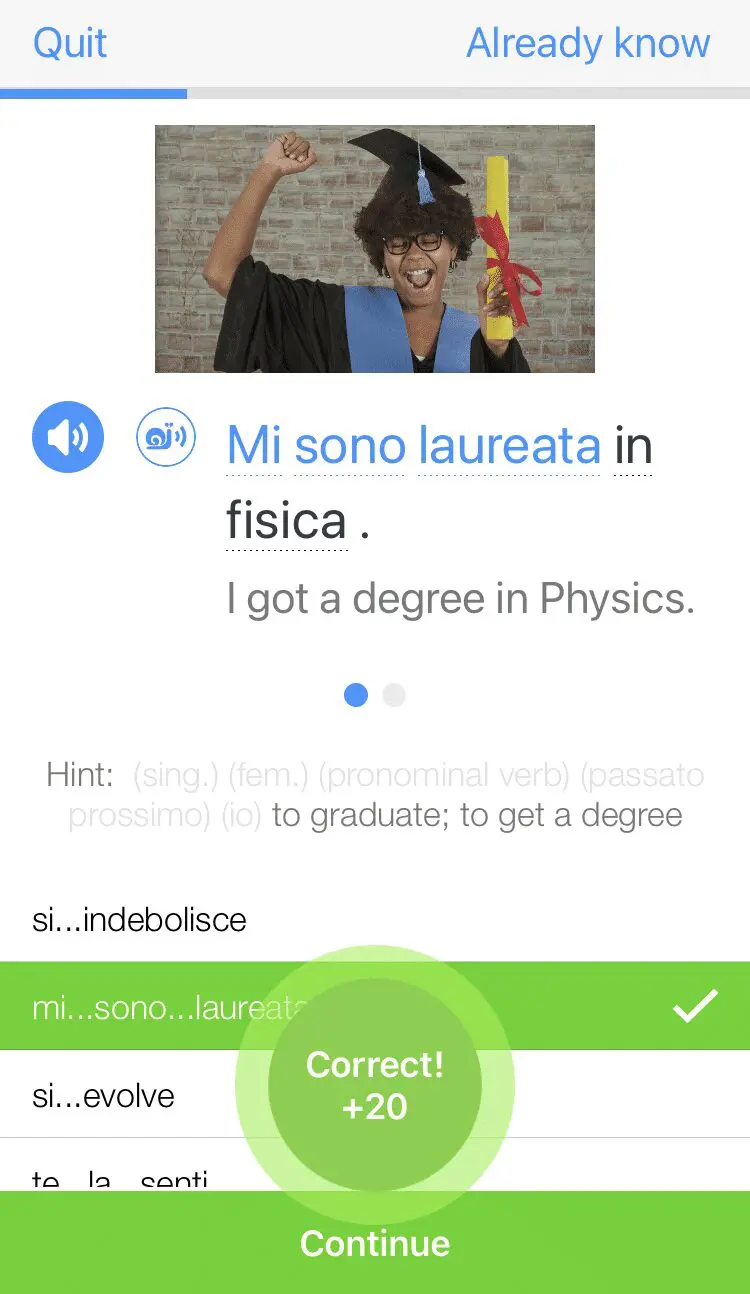

Once you've watched a video, you can use FluentU's quizzes to actively practice all the vocabulary in that video. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you’re on.

FluentU will even keep track of all the Italian words you’re learning, and give you extra practice with difficult words. Plus, it'll tell you exactly when it's time for review. Now that's a 100% personalized experience!

The best part? You can try FluentU for free with a trial.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)