Contents

How to Say “I Want” in Japanese (Explained with Ties)

It’s an unremarkable weekday evening and a salaryman is collapsed in the aisle of a dilapidated discount department store. He is, for some reason, sobbing.

A concerned customer service representative approaches him to ask what’s wrong, to which he replies: “I want to buy a ネクタイ (nekutai) — necktie!”

“How strange, it seems that all of our ties are located in the Japanese learning resources aisle. What in the world could a necktie have to do with learning Japanese?” The staff member replies.

It turns out a tie—or rather a -tai—is essential for saying “I want” in Japanese.

Read on to learn all about expressing wants and desires in Japanese in terms of the best mnemonic device: the humble necktie.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Expressing Desires in Japanese

One of the most common bits of advice given to people learning a new language is to think in their target language, not to translate into it. The problem with trying to translate directly is that what sounds natural in our native language doesn’t necessarily sound the same in our target language. This leads to output that’s often unnatural, even if it’s understandable.

It might be linguistically possible to translate anything into another language but for whatever reason—be it cultural differences, the simplicity of certain grammar points over others or even pop culture trends—the translation often gets a little blurred.

In this post, I’m going to discuss types of desire that are grammatically distinguished in Japanese but not in English. Even though all are encompassed by a mere two forms of the verb “to want” in English, trying to simply translate this “to want” into Japanese will probably yield incorrect results in three out of four situations.

To deal with this specific problem, and also to shift away from translating in your head, I’d like you to follow a two-step process.

1. Don’t think about the words you’re trying to translate but rather about the idea you want to express.

2. Learn how the Japanese language conveys this idea.

In other words, don’t think about how to say “I want a (something)” in Japanese. Instead, think about expressing “I want (something)” as opposed to “I want (to do something).”

1. Using ~欲しい (hoshii) with nouns: I want a necktie, not a bow tie

We’ll look at ~欲しい first because, although it’s backwards compared to English, the construction is very straightforward to make. Adding ~欲しい to a noun expresses your desire for that noun.

Note: When expressing desires with hoshii, the kanji spelling (欲しい) is more commonly used with nouns, while the hiragana spelling (ほしい) is used with verbs, such as when wanting to do something (as you’ll discover below in the third part of the post).

There are three steps:

1. Pick a noun. Any noun.

2. Add the particle が (ga). If you’re a little more advanced, you might sometimes use the particle は (wa) or even の (no).

3. Add 欲しい (hoshii [informal]) or 欲しいです (hoshii desu [formal]) after the particle.

欲しい is an い (i)-adjective and some of its basic conjugations look like this:

Present positive: 欲しい (hoshii) — want

Present negative: 欲しくない (hoshikunai) — don’t want

Past positive: 欲しかった (hoshikatta) — wanted

Past negative: 欲しくなかった (hoshikunakatta) — didn’t want

So, let’s go back to our story and rewind a little bit. Say that the staff member hadn’t clearly heard the salaryman because he was sobbing too loudly. She might say:

すみません。何が欲しいですか?

(Sumimasen. Nani ga hoshii desu ka?)

Excuse me. What is it that you want?

Prompted, the man repeats that he wants a necktie.

ネクタイ…ネクタイが欲しいです。

(Nekutai… nekutai ga hoshii desu.)

A necktie… I want a necktie.

The staff member nods and says, “Right this way, please.” She leads him down a few aisles and, outstretching her hand toward a rack of ties, uses an inversion of the structure we just learned.

欲しいものがありますか?

(Hoshii mono ga arimasu ka?)

Is there something that you want?

(In this case, saying 欲しいもの (hoshii mono) is a bit like saying “the thing that’s desired.”)

The salaryman blinks, incredulously, as he follows the shopkeeper’s gaze to realize that he’s looking at a shelf full of bow ties. A little frustrated, he responds:

ボウタイじゃなくて、ネクタイが欲しいです!

(Boutai janakute, nekutai ga hoshii desu!)

I want a necktie, not a bow tie!

If you want to specifically say that you don’t want something, は is often used instead of が. Our salaryman could just as well have said:

あっ、すみません。ボウタイは欲しくないです。ネクタイが欲しいです。

(Aa, sumimasen. Boutai wa hoshikunai desu. Nekutai ga hoshii desu.)

Ahh, sorry. I don’t want a bow tie. I want a necktie.

2. Using ~たい (tai) with verbs: I want to buy this necktie

If you don’t want a thing, but rather want to do something, you should use the ~たい form with a verb.

This form shows that you want to do the action that the ~たい is attached to.

This form can also be made in three steps.

1. Pick a verb. Any verb.

2. Conjugate that verb to its ~ます (masu) form.

3. Replace ~ます with ~たい.

To practice forming this verb form, see uTexas’s website. (Note that you’ll need to install a Japanese keyboard to use this website).

Here are some examples of the form in use:

見る (miru) — to see: 見る → 見ます (mimasu) → 見たい (mitai) — I want to see/look…

売る (uru) — to sell: 売る → 売ります (urimasu) → 売りたい (uritai) — I want to sell…

買う (kau) — to buy: 買う → 買います (kaimasu) → 買いたい (kaitai) — I want to buy…

It might be a little bit strange to think about, but the ~たい form of verbs is unique because it conjugates in the same way as い-adjectives do. That’s good for us, though, because it means that we can use the exact same conjugations for ~たい and ~ほしい!

Here’s the verb 買う (kau), for example.

Present positive: 買いたい (kaitai) ― I want to buy (something).

Present negative: 買いたくない (kaitakunai) ― I don’t want to buy (something).

Past positive: 買いたかった (kaitakatta) ― I wanted to buy (something).

Past negative: 買いたくなかった (kaitakunakatta) ― I didn’t want to buy (something).

To make these polite, simply add です (desu) at the end of each of the above examples.

Let’s go back to our story. The two are now standing in front of a rack of neckties. Observe how the staff member asks our salaryman for a bit more information.

では、どんなネクタイを買いたいですか?

(Deha, donna nekutai o kaitai desu ka?)

So, what sort of necktie do you want to buy?

(Note: While we normally use ~たがる (tagaru) form to talk about the desires of others, as we’ll learn in section four, the normal ~たい form is still used if you’re asking someone a question.)

The salaryman looks at the selection of ties and, a bit disappointed, uses an inversion of this structure, with the word もの (mono) — “thing.”

うーん、試着したいものが一つもないな。

(Uun, shichaku shitai mono ga hitotsu mo nai na.)

Hmm, I don’t even see one that I want to try on.

The staff member, shocked at this very blunt retort, responds:

あの、先程のボウタイをもう一度見たくないですか?

(Ano, sakihodo no boutai o mōichido mitakunai desu ka?)

Uhh, don’t you want to look at those bow ties from earlier one more time?

Unenthusiastically, he grabs a tie at random and begins walking toward the cash register.

じゃあ、これにします。

(Jaa, kore ni shimasu.)

I’ll take this one, then.

3. Using ~てほしい (te hoshii) with verbs: I want you to sell me this necktie

Japanese simply tacks that ~ほしい from earlier onto the end of a て (te) form verb to convey the idea of “wanting someone to do something for you.”

This is great because it means that we don’t have to complicate the sentence structure by adding a conjunction like “for” and we can also continue using the same conjugations we learned earlier. Again, there are only three steps.

1. Pick a verb. Any verb.

2. Conjugate that verb to its て form.

3. Add ~ほしい directly onto the end of the verb’s て form.

You can check your understanding of this over at JLPTsensei.

Here are some examples:

売る (uru) — to sell: 売る → 売って (utte) → 売ってほしい (utte hoshii) — I want you to sell…

飲む (nomu) — to drink: 飲む → 飲んで (nonde) → 飲んでほしい (nonde hoshii) — I want you to drink…

辞める (yameru) — to quit/resign: 辞める → 辞めて (yamete) → 辞めてほしい (yamete hoshii) — I want you to quit…

Back at the store, the disappointed salaryman approaches a cashier’s booth and, looking up, notices that the cashier is wearing an incredible tie. He exclaims:

うわ!そのネクタイ、売ってほしいです!売ってください!

(Uwa! Sono nekutai, utte hoshii desu! Utte kudasai!)

Holy smokes! I want you to sell me that necktie! Please sell it to me!

You might notice that the expressions “I want you to (do something)” and “please (do something)” sound quite similar. Saying “please” might be a little more direct, but aside from that, these forms are mostly interchangeable.

Thus, having been asked to sell the tie that’s part of his uniform, the cashier might respond:

怒らないで聞いてほしいのですが、このネクタイは非売品です。

(Okoranaide kiite hoshii no desu ga, kono nekutai wa hibaihin desu.)

Please listen and don’t be angry but this necktie isn’t for sale.

The salaryman, desperate, leaps over the table and tries to tear the tie from the cashier’s neck. They brawl for a few minutes before security arrives to take care of the situation. Panting and exasperated, the cashier might rudely exclaim:

この店に二度と来てほしくないです!

(Kono mise ni nidoto kite hoshikunai desu!)

I don’t want you to ever return to this store!

4. ~たがる (tagaru) with verbs: He wanted to kill me!

Unfortunately, it’s a little more difficult to talk about what other people want to do in Japanese. This is because Japanese marks words to show evidentiality or explain how a given piece of information was acquired. This normally requires grammar that’s more difficult than the ~たい form itself and there are a few ways to go about it, but to avoid complicating this post too much, I’ll only talk about one of them.

To express that “someone else wants to do something” you can:

1. Add a judgment to the end of a ~たい form verb.

2. Replace the ~たい in a ~たい form verb with ~たがる.

3. Add ~ですか (desu ka) to the end of a ~たい form verb to ask if someone else wants to do something.

If you’re curious, ~たがる is actually the normal ~たい form used with the suffix ~がる (garu). The suffix ~がる conveys the meaning of “seeming” or “showing signs of,” so ~たがる actually means something like “showing signs of wanting to do something.”

That aside, it’s okay to think of this form as meaning “[someone else] wants to do something.” For example:

殺す (korosu) — to kill: 殺す → 殺します (koroshimasu) → 殺したい (koroshitai) → 殺したがる (koroshitagaru) — (He) wants to kill…

~たがる conjugates in the same way as type one (う [u]) verbs like 怒る (okoru) — to be angry or 走る (hashiru) — to run. It’s often used in the ている (teiru) form.

Here are some basic formal conjugations of this:

Present positive: 殺したがっています (koroshitagatteimasu) ― (He) wants to kill…

Present negative: 殺したがっていません (koroshitagatteimasen) ― (He) doesn’t want to kill…

Past positive: 殺したがっていました (koroshitagatteimashita) ― (He) wanted to kill…

Past negative: 殺したがっていませんでした (koroshitagatteimasen deshita) ― (He) didn’t want to kill…

And here are the casual versions (the definitions are the same; only the level of formality changes here):

Present positive: 殺したがっている (koroshitagatteiru)

Present negative: 殺したがっていない (koroshitagatteinai)

Past positive: 殺したがっていた (koroshitagatteita)

Past negative: 殺したがっていなかった (koroshitagatteinakatta)

Let’s say that the store manager comes out to reprimand the cashier for not giving the customer respect due to his position. After all, the customer is king. Flustered, the cashier responds:

だ…だ…だけど、お客さんは私を殺したがっていました!

(Da… da… dakedo, okyaku san wa watashi o koroshitagatteimashita!)

B..bu..but, the customer wanted to kill me!

To which the manager responds,

そんなことがある訳ないでしょう。お客さんは、ただあなたのネクタイを触りたがっていただけでしたよ。

(Sonna koto ga aru wake nai deshou. Okyaku san wa, tada anata no nekutai o sawaritagatteita dake deshita yo.)

That’s crazy. All he wanted was to touch your tie!

After such a response, it might be safe to say that the cashier is 仕事を辞めたがっています (shigoto o yametagatteimasu) — wanting to quit his job!

As you can see with the example of buying a necktie shown in this post, seeing the language in action can help you understand how it’s used by native speakers. For example, you could try using the FluentU program to watch an array of Japanese media, like news clips and inspiring videos.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

While expressing desire in Japanese might be a bit more complicated than in English, the different ways to say “I want” in Japanese are also quite unambiguously marked.

With a bit of practice, it’ll become second nature before you know it!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

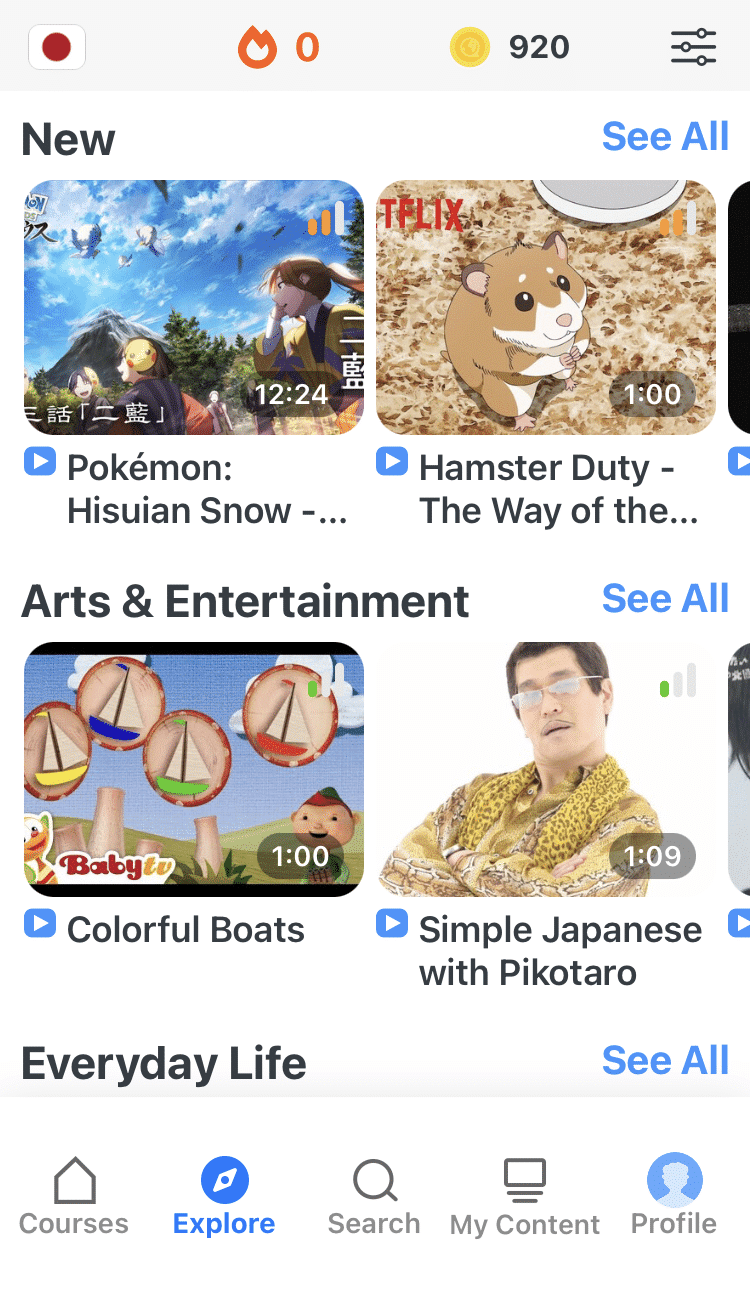

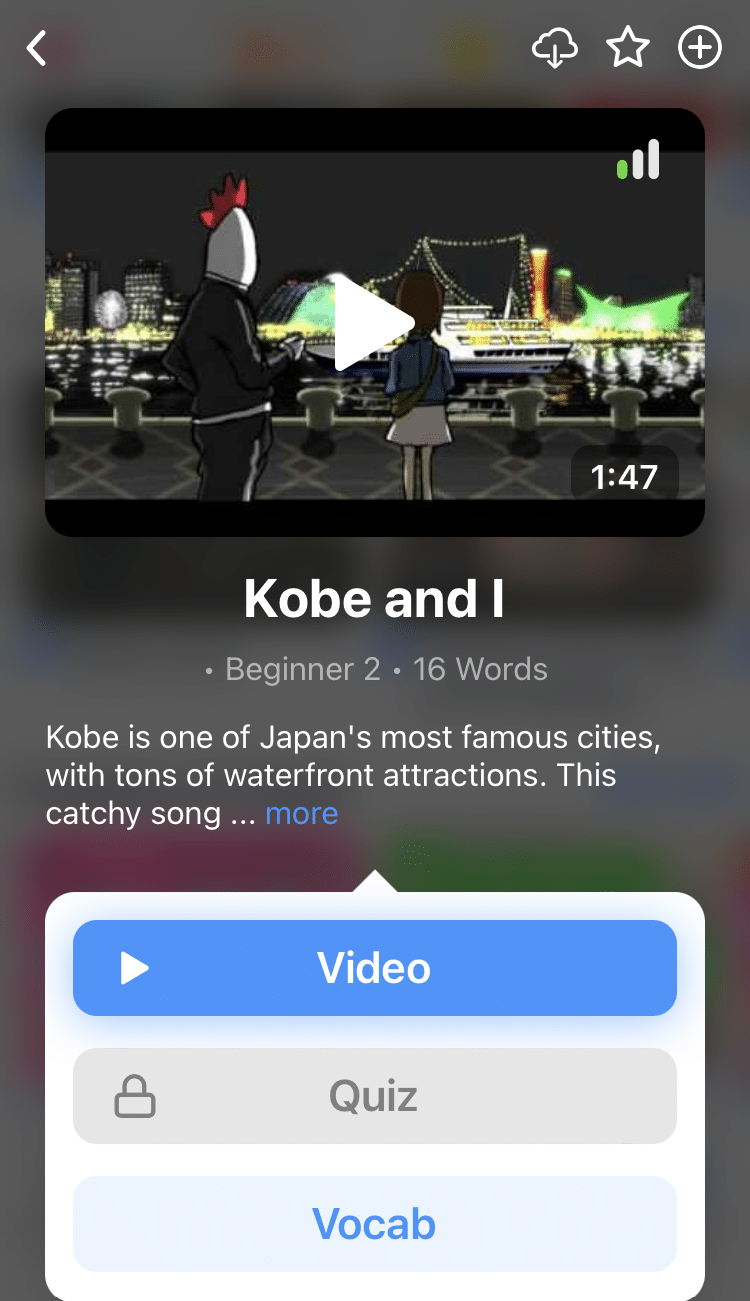

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

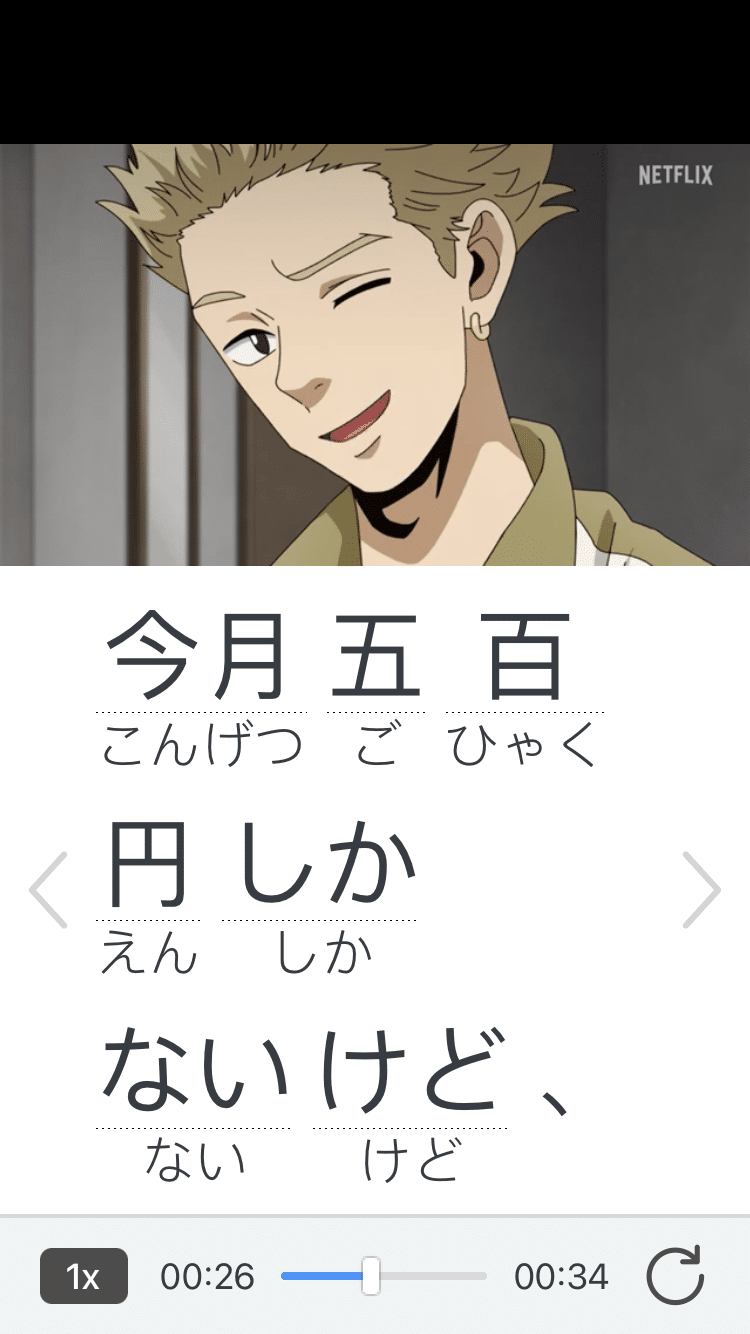

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

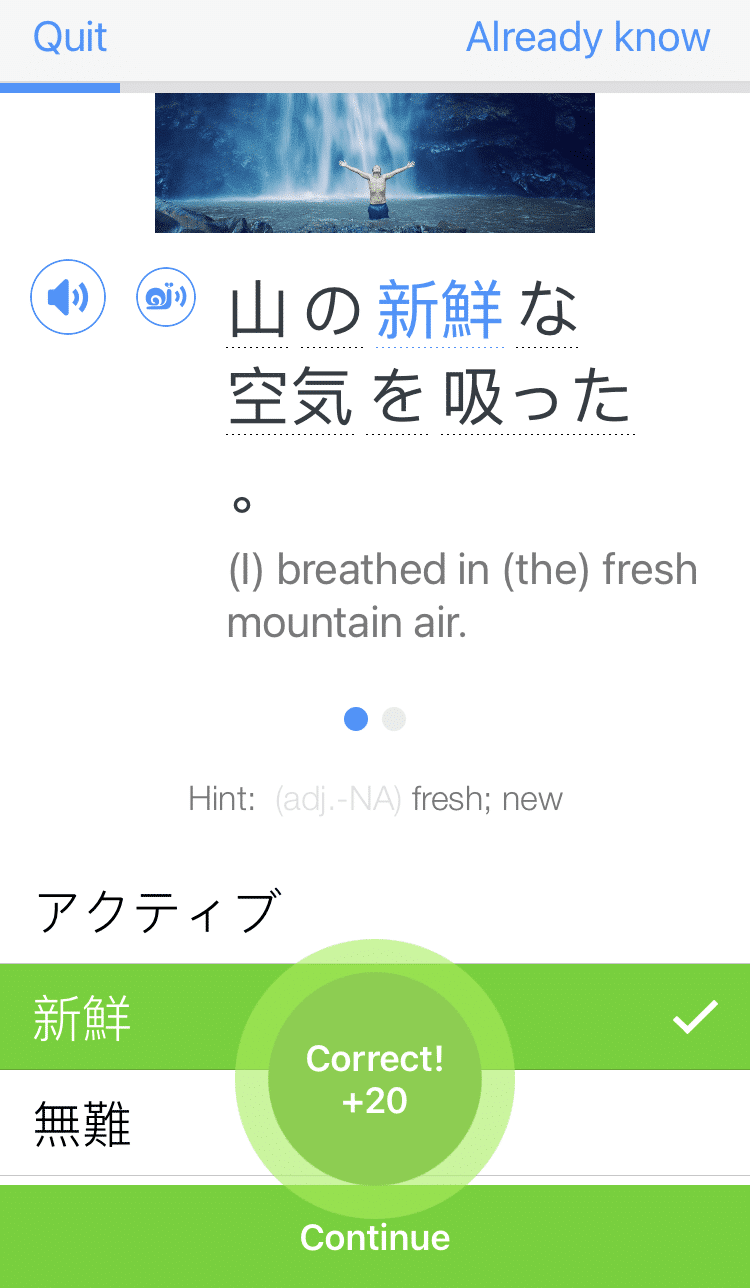

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)