Contents

- 1. ん Counts as One Mora

- 2. All Five Japanese Vowels Are Pronounced the Same

- 3. Avoid Turning Single Japanese Vowels into English Diphthongs

- 4. Understand Palatalized Sounds

- 5. Differentiate the Japanese /h/, /ç/ and /ɸ/

- 6. The Japanese “R” Is Very Different From the English One

- 7. し Doesn’t Sound Like “She” (And Also You May Have to Learn Some Chinese)

- 8. There Are Five Different “N” Sounds in Japanese

- 9. Japanese Has Pitch Accents (Just Like English!)

- Why Study Japanese Phonetics?

- And One More Thing...

Japanese Phonology: 9 Basics to Remember

Let me tell you a quick, personal story that I think underscores the importance of learning Japanese phonology or phonetics. It was a snowy day during my Japanese class at a small university in the middle of nowhere. As part of a grammar exercise, my teacher asked me a random question.

She said “サミさん!先生はかわいいと思いますか?( さみさん!せんせいは かわいいと おもいますか? ),” which meant “Sami! Do you think I’m cute?”

Trying not to look too relieved at the fact that it was an easy question, I nodded and responded: “うん。とっても怖いです! ( うん。とっても こわい です! )” Basically, I said: “Yeah, you’re incredibly scary!”

Shocked, my teacher made what sounded like a choking sound. A few people started laughing, but luckily, my friend quickly spoke up in my defense, telling the teacher that no, she’s cute, she’s really cute: “いや!かわいいです!先生はかわいいですよ! ( いや!かわいいです!せんせいは かわいい ですよ! )”

That was the moment I learned the value of Japanese phonetics and clear pronunciation. By the end, you’ll have all the information you need to pick out the differences between こわい (scary) and かわいい (cute)—and then some.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

1. ん Counts as One Mora

If you’ve tried shadowing Japanese speech, you might’ve seen that each of its mora (the building blocks of syllables) gets one beat and has the same length.

In other words, one mora is basically one kana (excluding small kanas like the ょ in ぎょ). So if you’re practicing pronunciation by clapping, the number of claps should correspond to the number of kana in a given word.

As most Japanese sounds are “consonant + vowel” pairs, the language itself sort of forces you to have a relatively consistent rhythm. That’s the general rule, anyway.

And then there’s ん .

Remember that ん is one mora and should be vocalized as such. For example, the word for “now” or 今度 (こんど) should get three beats (KO-N-DO), not two (KON-DO).

2. All Five Japanese Vowels Are Pronounced the Same

Japanese has five vowel sounds:

| Hiragana | Katakana | Phoneme | What It Sounds Like |

|---|---|---|---|

| あ | ア | /a/ | The "a" in "palm" |

| え | エ | /e/ | The "e" in "bed" |

| い | イ | /i/ | The "ee" in "seed" |

| お | オ | /o/ | "oh" minus the /ʊ/ sound near the end |

| う | ウ | /ɯ/ | The "oo" in "food" |

Aside from the fact that /i/ and /ɯ/ become voiceless when surrounded by certain consonants, these five vowels are always pronounced the same.

When I say “voiceless” in this context, it means your vocal cords don’t vibrate when producing these sounds. This is easier to understand when you feel it, though. Put your fingers on your neck as if you were checking your pulse. Say the phrase “Who are you?” out loud and then whisper the same phrase. Do you notice the difference?

As there are only five sounds, make sure you’re pronouncing these correctly! And the best way to do so is to practice, practice and practice some more.

Here’s the recommended method to practice sounds if you don’t have a speech teacher to consult (like I did):

- Find a video that features a native Japanese speaker talking and has accurate subtitles.

- Read a sentence from the subtitles.

- Listen to the native speaker say it.

- Re-read the sentence based on what you hear.

- Sit in front of a mirror and get a tape recorder rolling. Watch your mouth as you speak and listen to the recording. Compare it to the native speaker’s version and notice any differences.

- Make appropriate changes based on what you noticed and repeat the sentence again.

- Keep going until you perfect the sentence, then move on to another.

Luckily, you can find subtitled videos with native Japanese speakers on a language learning platform like FluentU.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Often, just hearing the correct pronunciation of a given sound is enough to improve your own pronunciation. Other times, you might hear the mistake but are unsure how to fix it.

If it’s the latter problem you’re dealing with, you can hire a tutor specifically to work on your pronunciation skills. A skilled teacher can show you what you can’t hear for yourself.

Even if you don’t have access to a professional tutor, a native speaker or language exchange partner can tell you if your recording sounds correct or if something sounds funny even if they can’t explain exactly why.

If you’re not ready for that sort of commitment, I’d also like to share an excellent YouTube series by Fluent Forever that looks at Japanese vowels—including the differences between the Japanese and English u sounds—in detail:

3. Avoid Turning Single Japanese Vowels into English Diphthongs

If you compare the IPA pages of English and Japanese I linked under “Why Study Japanese Phonetics?,” you’ll notice one staggering difference between the two: the English vowel section is huge compared to its Japanese counterpart.

One reason is that English has more vowel sounds than Japanese. There’s also the fact that English can be sneaky about the diphthong, a sound where there are two vowels in a single syllable.

For example, take the English word “no.” Say it as you normally would, then say it slowly. You should notice that it has two sounds: a short /o/ sound followed by the u sound /ʊ/. Essentially, you’re saying “nou.”

Now, apply this to Japanese. The no sound in の isn’t a diphthong. Here, you say the /o/, but stop before you get to the /ʊ/.

I don’t mean to say that Japanese never puts two vowels together. For example, the word 能力 ( のうりょく ) or “ability” features the /o/ sound in の and the Japanese /ɯ/ sound う. The same goes for the pronunciation of the name of Japan’s capital 東京 (とうきょう), where the two characters both have the /o/ and /ɯ/ sounds next to each other.

4. Understand Palatalized Sounds

One concept that’s essential to Japanese pronunciation is palatalization. You may not be familiar with this term, but it’s something you often do without realizing it.

For example, here’s a video with exercises explaining how to make the palatalized sounds of English:

And here’s another video demonstrating sound changes in Japanese—i.e., what changes the diacritic markers in は→ ば ・ ぱ actually represent:

While studying hiragana and katakana, you may have learned that “small” kanas can be appended to bigger ones to make new sounds—such as び and よ to make びょ.

When you add a small や , ゆ or よ to Japanese consonants, you’re actually representing a palatalized sound.

For example, the g sound in ぎょ and ご aren’t the same.

Try it for yourself: repeat the sounds slowly back and forth. Close your eyes and focus your attention on your mouth. Where are the sounds coming from? What does your mouth feel like? You should feel that the sound in ぎょ seems to come from a slightly “higher” place than that of ご.

If you’re struggling, I think it helps to whisper the sounds. Again, ぎょ features a palatalized /g/, while the sound in ご is a plain /g/.

5. Differentiate the Japanese /h/, /ç/ and /ɸ/

While は, ひ , ふ , へ and ほ are all transcribed as beginning with the letter h (as you can see in this study), there are actually three different initial consonants here: /h/, /ç/ and /ɸ/.

Now, go back to ご vs. ぎょ and find the difference in feeling once more, then try again with ほ and ひょ. You should feel a difference in position. And if you hold your hand in front of your mouth, you should also notice much less air hitting your hand when you say ひょ.

The sound in ひ, /ç/, is a palatalized variant of the /h/ sound, while /ɸ/ is a new yet accessible sound that’ll take a bit of playing with your lips. This is important because ふ has a combination of consonant and vowel sounds that don’t exist in English: /ɸ/+/ɯ/.

So, what’s the difference between the /f/ (as in “fan”) that we’re all familiar with and /ɸ/ as in Mt. 富士 (ふじ)?

Well, when you look at this visual IPA chart, you can see that the technical term for /f/ is “labiodental fricative” whereas /ɸ/ is “bilabial fricative.” That’s fancy speak for one sound that involves your lip touching your teeth and another that involves both of your lips but not your teeth.

Pretend that you’re blowing out a candle and freeze in the middle of blowing. Pay attention to how your mouth feels, and then maintain that position while saying ふ. If you’re unsure, check out this link from Wasabi Japanese and compare your pronunciation to that of a native speaker’s.

6. The Japanese “R” Is Very Different From the English One

My Japanese teacher (the one I mentioned in the intro) once said that the most difficult English word to pronounce for Japanese speakers is “really.” That’s because, in terms of tongue position, the Japanese /ɾ/ is somewhere in between the English /r/ and /l/.

Here’s a good explanation of the Japanese r sound:

Pretend you’re singing a Christmas carol—“la la la la la, la la la la!”—and pay attention to where your tongue is. It should be just above your upper teeth, almost touching them. Now, ditch the ugly sweater and sing the beginning of an un-creative cheer—“ra ra ra!”—and again, pay attention to where your tongue is.

Then, say la, and without stopping your breath, say r, so you get a nonsense la-err type sound. You should notice that you basically trace a tiny line back from your l tongue position to get to your r tongue position.

Now that you’ve got that figured out, pick a position in the middle and say a few Japanese words that begin with this r sound like ラーメン (“ramen”). If the sound isn’t an l sound, not quite an r sound but also seems to be somewhere in the middle, you’re on the right track!

7. し Doesn’t Sound Like “She” (And Also You May Have to Learn Some Chinese)

Contrary to what you may have been taught, し does not sound the same as “she.”

The sound in “she” is called a “voiceless postalveolar fricative” and it looks like /ʃ/. Meanwhile, the sound in し (and its katakana counterpart シ ) is a “voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative” and looks like /ɕ/.

They’re different sounds.

Unfortunately, there aren’t a ton of good resources on how to pronounce し, so I’m going to direct you to a few videos aimed at Mandarin Chinese learners, since the /ɕ/ sound exists in both languages.

Another sound you’ll hear in both Mandarin and Japanese is /tɕ/. Japanese represents this sound with the characters つ in hiragana and ツ in katakana.

You can start by watching a video from OLS Mandarin, which compares several Mandarin consonant sounds. Pay close attention to the pinyin labels of x and j, which roughly correspond to the sounds of し and つ, respectively:

Try to hear the difference between the two sounds, and then look into a few videos that talk about the sounds more specifically, like the ones by Yoyo Chinese (for し and for ち):

If you’re willing to go for a more precise explanation and don’t mind learning a bit more about the Mandarin sh and zh, check out the excellent videos by Litao Chinese (for し and for ち):

Unfortunately, the Japanese じ sound (variably, /ʑ/ and /dʑ/) doesn’t exist in Mandarin. The only difference between しand じ is that し is unvoiced (your vocal chords don’t vibrate) while じ is voiced (your vocal chords should vibrate).

8. There Are Five Different “N” Sounds in Japanese

To wit, they are:

- The normal n sound or /n/. For example, you have 海苔 ( のり ), the dried seaweed often used in Japanese food.

- The palatalized /ɲ/. This comes before consonants other than い or the little よ, や and ゆ sounds.

- The n that becomes m. If you’ve ever puzzled over the fact that 頑張る ( がんばる ) or “good luck/do your best” seems to be frequently misspelled as gambaru in some textbooks or phrasebooks, you’re likely familiar with the rule that /n/ becomes /m/ (as in “mom”) before /b/ (as in boy) or /p/ (as in pot).

- The /ŋ/ sound. This sounds like the ng sound of -ing in words like “going” or “sing.” It happens when ん comes before a /k/ or /g/ sound.

- The /ɴ/ sound. This is the sound of ん when it occurs before a pause or, as Wikipedia puts it, at the end of an utterance like in すみません… or “I’m sorry/excuse me…” By the way, here’s a good thread explaining how to pronounce すみません.

9. Japanese Has Pitch Accents (Just Like English!)

Similar to English (where the word “certain” is pronounced as CER-tain and not cer-TAIN), words in Japanese are emphasized in a specific way.

You’ll want to remember that Japanese words are all stressed equally, but they follow a few special patterns of high and low pitches. 銀行 (ぎんこう) or “bank,” for example, starts with a low pitch followed by morae of three high pitches.

Although there are a few main patterns that Japanese words follow, these patterns aren’t fixed and vary depending on what’s going on in a sentence. For example, in the Tokyo/standard dialect of Japanese, there are two fundamental rules:

1. The first two morae of a word won’t have the same level of pitch. In other words, if the first mora is high, then the second will be low and vice versa.

2. Once the pitch of a word drops, it won’t come back again. Unlike Mandarin Chinese, standard Japanese lacks the falling-then-rising intonation of words like 买 or “buy.”

If all of this is giving you a headache, I suggest spending some time learning about how pitch accent works. You’ll also want to learn a handful of common words for each pattern so you get a sense for how each one feels. Then, just pay attention to their accent as you consume media or listen to people talking.

In case you’d like to look at this in depth, a guy named Dogen has released a comprehensive series on the topic.

Why Study Japanese Phonetics?

When I began studying Japanese, I was told that Japanese pronunciation was very easy. In fact, we only spent one class period on pronunciation for the following reasons:

- The language is atonal. It’s not like, say, Mandarin Chinese where the way you pronounce certain words changes their meaning and the character you use to write them. For example, the Chinese characters for “buy” and “sell” are 买 and 卖, respectively. They both sound like “mai,” except the former has a falling then rising intonation, while the latter only has a falling intonation.

- Spelling is phonetic and pronunciation is consistent. Put in another way, words sound like they look and look like they sound. Even someone who’s never studied Japanese before could read a text written in romaji and be understood without much trouble (unlike someone studying French, for example).

- It’s relatively easy for native speakers of languages like Spanish. If you pronounce the Japanese vowels the way you do in Spanish, you’ll be just fine.

This all begs a question you’re probably thinking right now, given that you’ve decided to read an entire article about the subject: if Japanese pronunciation is so easy, why would someone devote time to studying the phonetics of Japanese—or what Webster’s English Language Learner Dictionary defines as “the study of speech sounds?”

The reason all boils down to this: Japanese has sounds that don’t exist in English and vice versa. Go spend a few minutes looking at the IPA pages for English and Japanese, and you’ll find that the two languages may have similar sounds but they’re not exactly identical.

Wow, that was a journey! We’ve just covered a ton of information about Japanese phonetics. At this point, you’re probably asking yourself if it’s worth all the effort to figure this stuff out—and honestly, that’s a question for you to answer.

If you pronounce Japanese words the “wrong” way (whatever that means) and native speakers can still understand you, that’s all right. After all, English speakers think a French accent sounds romantic, and you’ll probably get a pass for being a foreigner anyway.

But if your goal is to become fluent in spoken Japanese, learning about its phonetics will get you there. Gambatte, ne!

And One More Thing...

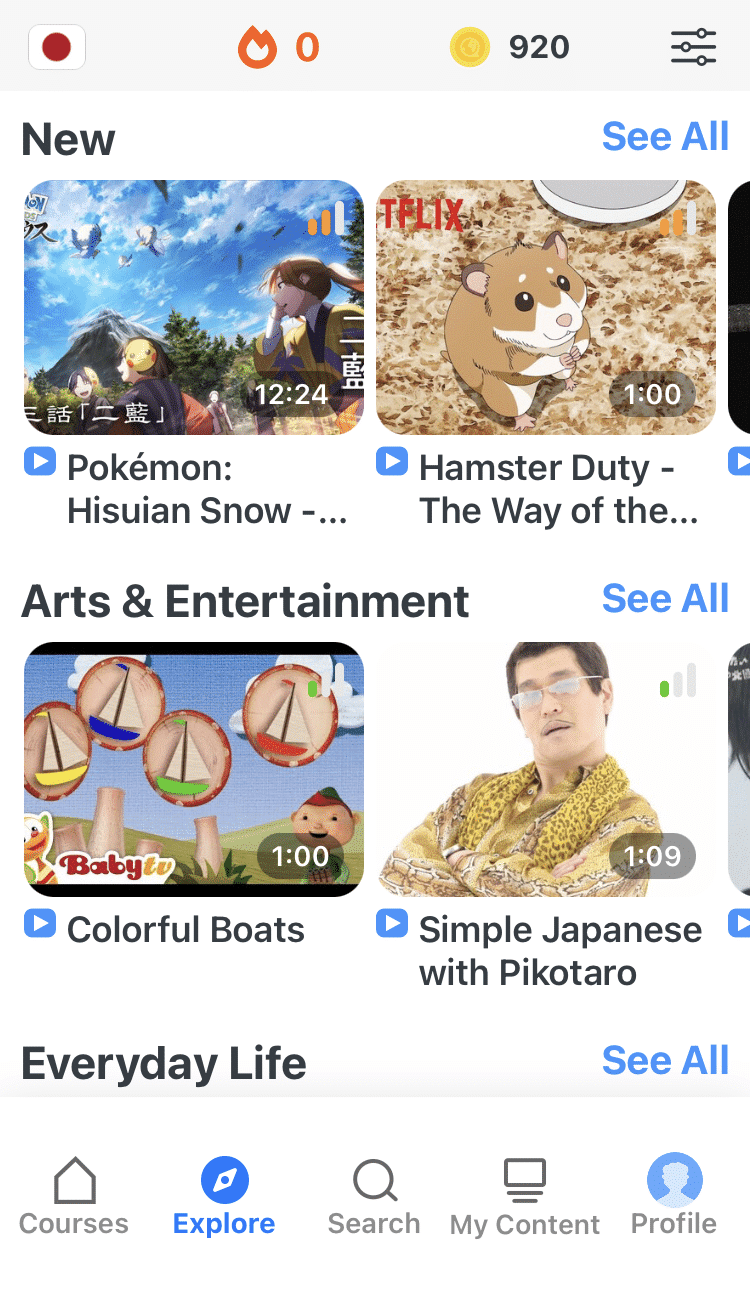

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

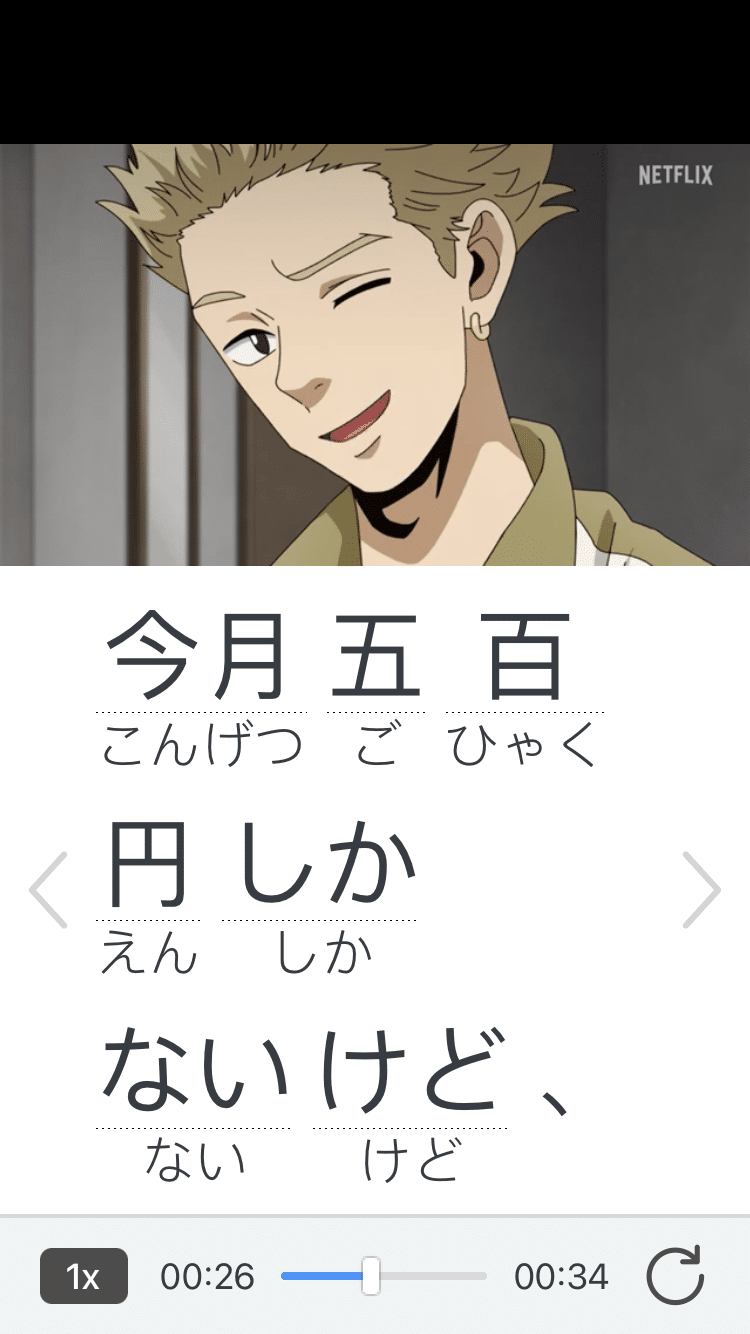

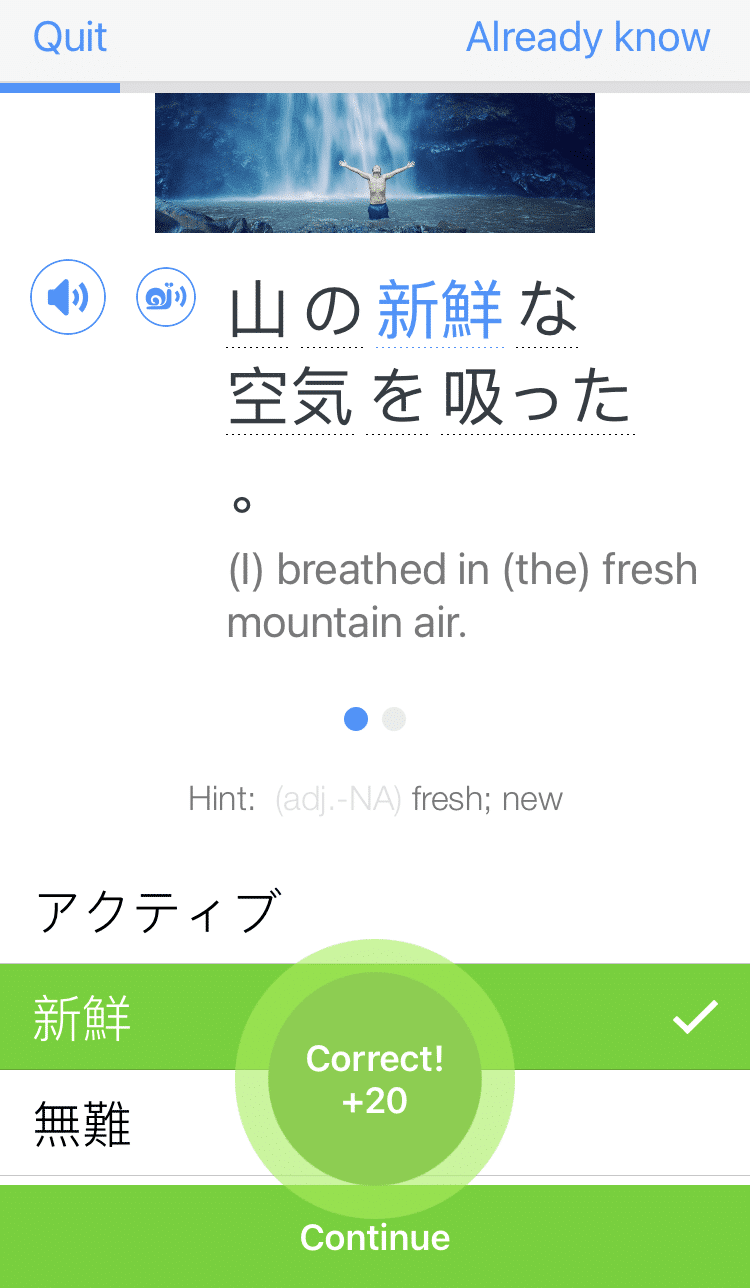

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

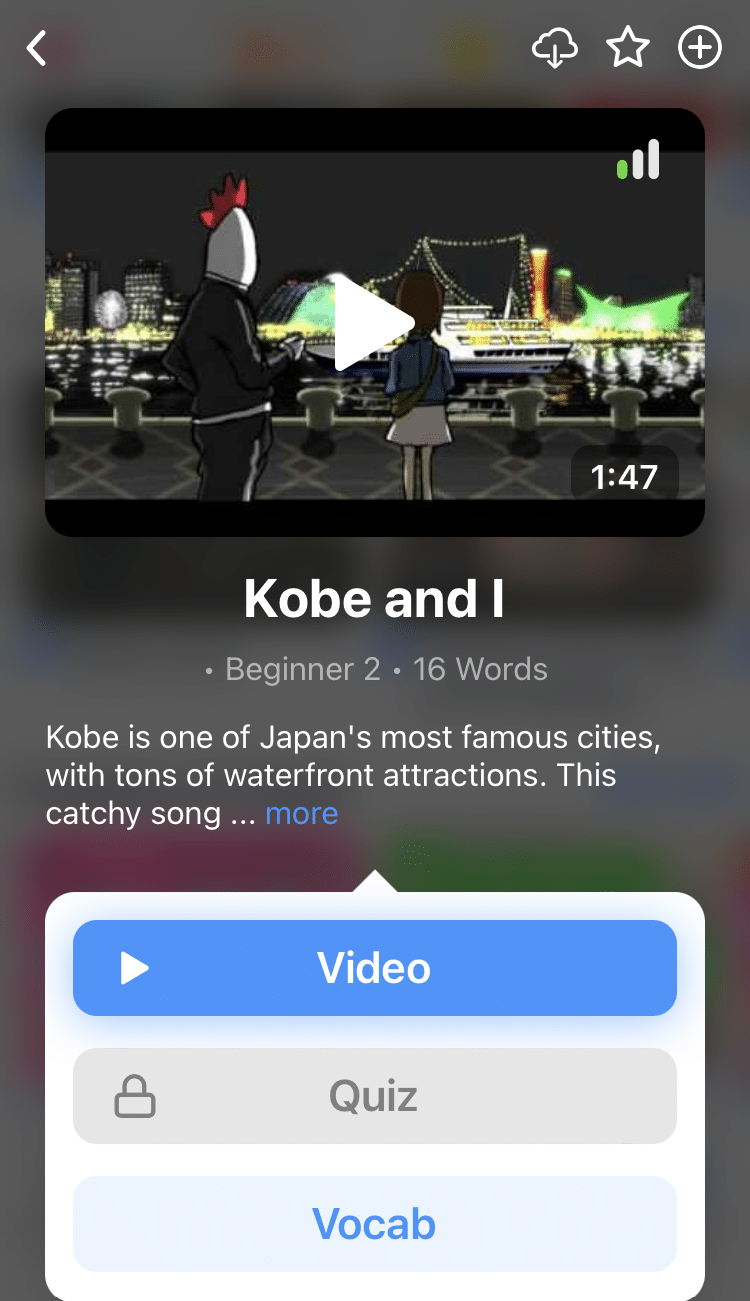

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)