An Introduction to Japanese Sentence Structure

So you’ve learned some Japanese vocabulary.

Now, how do you string it into coherent sentences?

You’ll need to learn about Japanese word order, correct particle usage and the omnipresent です (“desu”).

This quick introduction will help you figure out how to get started with Japanese sentence structure.

Contents

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

The Japanese Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) Structure

Japanese sentences follow an SOV format.

SOV means “subject-object-verb.” This means that the subject comes first, followed by object or objects, and the sentence ends with the verb. You’ll see lots of examples of this throughout this article.

Let’s look at an example:

ジンボはリンゴを食べる。

じんぼはりんごをたべる。

Jimbo — an apple — eats

(Jimbo eats an apple.)

“Jimbo” is the subject, “eats” is the verb and “an apple” is the object. This sentence follows the SOV formula.

The Japanese Copula, です

If you’ve ever heard someone speak Japanese, be it in real life or on TV, you’ve almost certainly come across the Japanese word です.

です is one of the most basic terms in the Japanese language, literally meaning “to be” or “is.” Many think of it as just a formality marker, but it serves all sorts of functions.

です is a copula, meaning that it connects the subject of the sentence with the predicate, thus creating a complete sentence. The most basic Japanese sentence structure is “A は B です” (A is B).

My name is Amanda.

私はアマンダです。

わたしはあまんだです。

He is American.

彼はアメリカ人です。

かれはあめりかじんです。

です also serves to mark the end of a sentence, taking the place of a verb. Also, です never comes at the end of sentences that have verbs ending in ます.

Tom likes tea.

トムさんはお茶が好きです。

とむさんはおちゃがすきです。

Tom drinks tea.

トムさんはお茶を飲みますです。(Incorrect)

トムさんはお茶を飲みます。(Correct)

とむさんはおちゃをのみます

Past Tense with でした

When describing something that happened in the past, です turns into でした.

The exam was easy.

試験は簡単でした。

しけんはかんたんでした。

Yesterday was my birthday.

昨日は私の誕生日でした。

きのうはわたしのたんじょうびでした。

Levels of Formality of です

As with many words in Japanese, です comes in different levels of formality: だ, です, である and でございます:

- です is the basic polite form and will be most useful in everyday conversation.

- だ is found in casual speech among friends or family.

- である is used in formal written Japanese, such as in newspapers.

- でございます is the most formal form, used when speaking to your superior or someone important.

If you’re at a loss for which form to use, just stick with です. The person you’re talking to will know you’re trying to be polite!

Japanese Verb Placement

As I just said, Japanese verbs have only two tenses: past and non-past.

Like English, you form the past tense by changing the end of the verb.

I ran to the store.

私は店に走りました。

わたしはみせにはしりました。

Mayu studied last night.

昨日の夜、まゆさんは勉強した。

きのうのよる、まゆさんはべんきょうした。

Alice made cookies.

アリスはクッキーを作った。

ありすはくっきーをつくった。

Unlike English, Japanese verbs are highly regular.

Japanese Verb Categories

Many can be divided into two categories: う verbs and る verbs. It’s important to know the difference between the two, as they conjugate differently.

Each verb also comes in a dictionary form and a polite form—the dictionary form is used for casual speech, or if you’re trying to look it up in, well, a dictionary.

う verbs are verbs which end in the sound う, ある, うる or おる in their dictionary forms. They become polite when you drop the う and replace it with います.

- 話す/話します (はなす/はなします, to talk)

- 行く/行きます (いく/いきます, to go)

- 飲む/飲みます (のむ/のみます, to drink)

- 作る/作ります (つくる/つくります, to make)

Verbs ending in the sound いる and える are almost always る verbs. る verbs become polite by dropping the る and replacing it with ます。

- 食べる/食べます (たべる/たべます, to eat)

- 見る/見ます (みる/みます, to see)

- 起きる/起きます (おきる/おきます, to get up)

There are only two significantly irregular verbs, する (to do) and くる (to come). Their polite forms are します and きます, respectively.

Japanese Verb Negations

Negative forms are also made by changing the end of the verb, which varies depending on the verb type. For instance:

- For う verbs, replace the う sound with あない.

- For る verbs, drop る and replace it with ない. する becomes しない, and くる becomes こない.

You can learn much more about negating Japanese verbs here.

Using Verbs to Express Nuances

Although there are only two tenses, verbs in Japanese change to express nuances. Japanese sentence structure is a type that’s called agglutinative.

This is a fancy word used by linguists which means, in layman’s terms, “You add a bunch of stuff to the end of verbs.” Each verb has a root form that ends with てor で.

You can add to these root form endings to give more meaning. But this isn’t really essential for making easy Japanese sentences, so we’ll pass over it for now.

Japanese Post-positions

While English has prepositions, Japanese has post-positions.

Prepositions are words that show relationships between parts of a sentence, such as “to,” “at,” “in,” “between,” “from” and so on.

They come before nouns in English. But in Japanese, they follow nouns. へ means “to,” so this next sentence is literally, “Spain to went.”

I went to Spain.

スペインへ行きました。

すぺいんへ いきました。

In the next example, 彼女 means “her,” so what you’re saying is “her from” rather than “from her.”

Did you hear from her?

彼女から聞きましたか?

かのじょから ききましたか?

Japanese Particles

In the same vein as post-positions, Japanese has little grammatical pieces called particles.

Japanese particles come directly after the noun, adjective or sentence they modify, and are crucial to understanding the meaning of what’s being conveyed.

There are dozens of particles in Japanese, but we’ll cover nine common ones: は, が, を, の, に, へ, で, も and と.

は (topic marker)

は marks the topic of the sentence, and can be translated as “am,” “is,” “are” and “as for.” Take note that though it uses the character for ha, it’s actually pronounced wa.

I am a student.

私は学生です。

わたしはがくせいです。

The pen is black.

ペンは黒いです。

ぺんはくろいです。

In these sentences, 私 (わたし, I) and ペン (pen) are marked by は, making all of the information that follows directly pertaining to 私 and ペン, respectively.

が (subject marker)

が indicates as well as emphasizes the subject of the sentence, the one performing the action. In addition, it can join sentences as a “but,” and serves as the default particle for question sentences.

That bird is singing.

あの鳥が鳴いています。

あのとりがないています。

Who will be coming?

誰が来ますか?

だれがきますか?

Yuta studied abroad in China (emphasis on Yuta)

ゆうたさんが中国に留学しました。

ゆうたさんがちゅうごくにりゅうがくしました。

は and が are two particles that can be easy to get mixed up, so here are some tips for keeping them straight:

は is a general subject, while が is more specific. は is also used as a contrast marker in sentences with が, to show that there is some sort of difference between the two subjects:

My little sister doesn’t like cats, but she likes dogs.

妹は猫が嫌いだけど、犬は好きです。

いもうとはねこがきらいだけど、いぬはすきです。

を (object marker)

を shows the direct object of a sentence, meaning that it indicates that the verb is doing something or the verb is being done to the object. It follows nouns and noun phrases.

I eat vegetables.

私は野菜を食べます。

わたしはやさいをたべます。

Tonight, he will make dinner.

今夜、彼は夕食を作ります。

こんや、かれはゆうしょくをつくります。

In the first sentence, “vegetables” are the object, and “eat” is the action being done to them. The same goes for “dinner” and “make” in the second sentence.

の (possession marker)

の serves as a possessive particle, marking something as belonging to something else. It also serves as a generic noun, meaning “this one.”

That is the teacher’s bag.

それは先生のかばんです。

それはせんせいのかばんです。

I want to buy the yellow one.

黄色いのを買いたいです。

きいろいのをかいたいです。

に (time and movement marker)

に is the movement and time particle, which shows the place towards which a thing moves when accompanied by a moving verb.

It also indicates destinations and places where something exists when it’s accompanied by いる/ある. It can translate as “to,” “in/at” or “for.”

Yukako came to the movie theater.

ゆかこさんは映画館に来ました。

ゆかこさんはえいがかんにきました。

There is a bench in the park.

公園にベンチがあります。

こうえんにべんちがあります。

へ (direction and destination marker)

へ is a directional particle similar to に, but used exclusively for marking destinations. へ emphasizes the direction in which something is heading. It’s also read as e despite being spelled he.

I went to the restaurant.

私はレストランへ行きました。

わたしはれすとらんへいきました。

When indicating direction, に and へ are often interchangeable, whereas へ is never used as “for/at.”

で (location and means marker)

で can have several meanings, depending on the context. It can designate the location of an action, show the means by which an action is carried out or connect clauses in a sentence.

Shigeo went shopping at the department store.

しげおさんはデパートで買い物しました。

しげおさんはでぱーとでかいものしました。

I came to Canada by plane.

私は飛行機でカナダに来ました。

ひこうきでかなだにきました。

That person is famous and kind.

その人は有名で、優しいです。

そのひとはゆうめいで、やさしいです。

も (similarity marker)

も, which translates as “also/too,” is used to state similarities between facts. It comes after a noun, replacing the particles は and が.

Both rice and bread are tasty.

パンもごはんもおいしいです。

ぱんもごはんもおいしいです。

Erika’s hobby is hiking. My hobby is also hiking.

エリカさんの趣味はハイキングです。私の趣味もハイキングです。

えりかさんのしゅみははいきんぐです。わたしのしゅみもはいきんぐです。

On a similar note, saying 私もです (わたしもです, me too) is enough to show that you agree with what someone said.

と (noun connector)

と is used to make a complete list of nouns. It corresponds to “and.”

That store sells sandwiches and coffee.

あの店はサンドイッチとコーヒーを売っています。

あのみせはさんどいっちとこーひーをうっています。

She went to the movies with Brad and Connor.

彼女はブラッドさんとコナーさんと映画を見に行きました。

かのじょはぶらっどさんとこなーさんとえいがをみにいきました。

Japanese Adjective Placement

Like in English, adjectives come before nouns in Japanese. A blue car in English is still a blue car in Japanese, but instead, you’d say 青い車 (あおいくるま).

There are two types of Japanese adjectives: い adjectives and な adjectives. The difference is in their conjugation.

い adjectives end in the character い, such as 面白い (おもしろい, interesting) and 難しい (むずかしい, difficult). The exception is words ending in えい, like きれい (beautiful), which are な adjectives.

い Adjectives

い adjectives come directly before the noun that they modify.

Cute cat

かわいい猫

かわいいねこ

Slow bus

遅いバス

おそいばす

“Expensive shirt”

高いシャツ

たかいしゃつ

な Adjectives

な adjectives, with a few exceptions like the aforementionedえい ending, don’t end in い. While they go before nouns just like い adjectives, the character な is placed between the adjective and the noun.

Kind teacher

親切な先生

しんせつなせんせい

Rude child

失礼な子供

しつれいなこども

Safe town

安全な町

あんぜんなまち

Modifying Japanese Adjectives

One thing that’s a little tricky is that い adjectives change to express negative or past tense. This is done by dropping the final い in the word and tacking on modifiers. For instance:

The word for cold is 寒い (さむい) but if you’re talking about yesterday being cold, you would say 寒かった (さむかった). If it’s not cold, you’d say 寒くない (さむくない).

な adjectives are modified exactly like nouns. For example:

The word 静か (しずか) means quiet. To say something was quiet, you’d say 静かだった (しずかだった), and to say it’s not quiet, you’d say 静かではない (しずかではない) or 静かじゃない (しずかじゃない).

Like verbs, these changeable adjectives are also agglutinating, which means you can add stuff to them.

Japanese Question Structure

Finally, questions are much easier to form in Japanese than in English. To ask a yes or no question, you simply tack on か at the end of the sentence.

Is he a nice person?

彼は優しい人ですか?

かれはやさしいひとですか?

For what we’d call the “Wh- questions” in English, you simply substitute the question word in most cases:

What did you eat?

何を食べましたか?

なにをたべましたか?

I ate octopus.

タコを食べました。

たこをたべました。

Where is he?

彼はどこにいますか?

かれはどこにいますか?

He is at the house.

彼は家にいます。

かれはいえにいます。

Inferred Subjects in Japanese

By now, you’ve probably noticed that the subject disappears from the sentence quite often. This is a particular quirk of the Japanese language where the subject is inferred whenever possible.

But there are hints that tell you what or who you’re talking about. It actually works the same way as pronouns in English. For example:

My father is a teacher. He teaches at the university. On weekends, he barbecues and drinks beer. He likes football but he doesn’t like baseball.

The way I see it, Japanese does the same thing but goes one step further—the subject disappears completely. In this next example, it’s inferred that the speaker is referring to himself:

私は先生です。英語を教えています。

わたしは せんせいです。えいごをおしえています。

I am a teacher. Teach English.

Breaking Japanese Sentence Structure Rules

Although technically the verb always comes at the end of a Japanese sentence, this isn’t always the case. Unlike in English, the sentence structure is very free.

In writing, you’d stick to the actual grammatical rules; in speaking people often break the rules and put parts of the sentence wherever they see fit.

For example, if you want to say, “I ate fried chicken,” the grammatically correct Japanese sentence would be:

私はフライドチキンを食べた。

わたしは ふらいどちきんをたべた。

I — fried chicken — ate

But in casual, everyday conversation, you can move the parts around and it’s no problem:

食べた、フライドチキン。

たべた、ふらいどちきん。

Ate — fried chicken

フライドチキン食べた、私。

ふらいどちきんたべた、わたし。

Fried chicken — ate — I

But each of the above utterances means the same thing. In English, it would be mighty strange if you said this.

For the purposes of learning basic Japanese sentence structure, however, stick to Subject-Object-Verb. That’s proper Japanese and you can learn the more casual forms of speech later.

A good way to remember the sentence structure is by exposing yourself to the language as much as you can.

For instance, you can use an immersive program like FluentU to watch authentic Japanese videos.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

With a bit of patience and practice, you’ll soon be on your way to speaking natural Japanese!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing…

If you’re like me and prefer learning Japanese on your own time, from the comfort of your smart device, I’ve got something you’ll love.

With FluentU’s Chrome Extension, you can turn any YouTube or Netflix video with subtitles into an interactive language lesson. That means you can learn Japanese from real-world content, just as native speakers actually use it.

You can even import your favorite YouTube videos into your FluentU account. If you’re not sure where to start, check out our curated library of videos that are handpicked for beginners and intermediate learners, as you can see here:

FluentU brings native Japanese videos within reach. With interactive captions, you can hover over any word to see its meaning along with an image, audio pronunciation, and grammatical information.

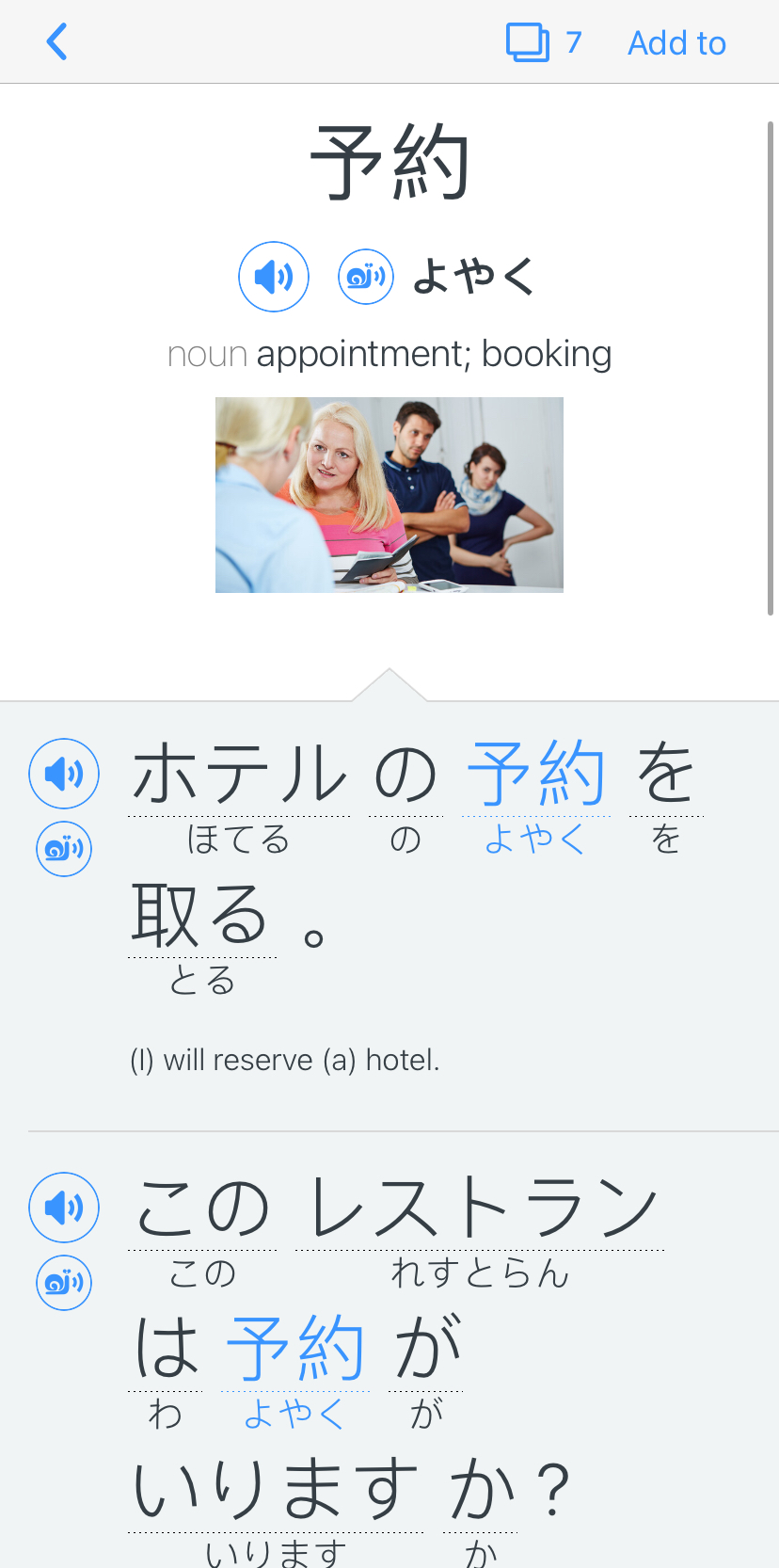

Click on a word to see more examples where it's used in different contexts. Plus, you can add new words to your flaschards! For example, if I tap on 予約, this is what pops up:

Want to make sure you remember what you've learned? We’ve got you covered. Each video comes with exercises to review and reinforce key vocab. You’ll get extra practice with tricky words and be reminded when it’s time to review so nothing slips through the cracks.

The best part? FluentU tracks everything you’re learning and uses that to create a personalized experience just for you. Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download our app from the App Store or Google Play.

Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)