200+ Katakana Words: Your Introduction to Japanese Loanwords

In a nutshell, katakana uses characters to represent syllables (instead of single letters like an alphabet) and it’s used primarily for re-imagining foreign words in the Japanese language.

Below, I’ve put together a guide on everything you need to know about katakana.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Is Katakana?

As I’ve mentioned, 片仮名 (かたかな) — katakana is a Japanese writing system used to transcribe foreign words, sound effects, titles and loan words into Japanese words.

Think of it this way: To read Japanese words, you might have used ローマ字 (ろーまじ) — rōmaji, or Latin-based script that shows you how to sound out each syllable with letters familiar to you. (“Rōmaji” is an example of rōmaji!)

Japanese speakers use the same concept with foreign words. Just as English speakers use rōmaji, Japanese speakers use katakana.

Katakana is syllable-based, meaning each character in its “alphabet” represents a particular syllable or sound. Those syllables are put together to sound out foreign words in a way Japanese speakers can pronounce and understand.

Katakana is mainly used for writing loanwords or 外来語 (がいらい ご) — gairaigo, words from other languages that become part of the Japanese language. (This happens in English, too: for example, “karaoke” is a Japanese loanword that’s now part of the English vocabulary.)

So why bother learning katakana if it’s just a bunch of foreign (often English) words rewritten for Japanese readers?

Well, katakana is just as important as 漢字 (かんじ) — kanji and 平仮名 (ひらがな) — hiragana. It’s used frequently, especially with Western concepts, modern technologies and internet communication.

Therefore, if you want to really take your fluency to the next level, you’ll need to get a grasp on katakana syllables and common words.

Meet the Syllabary: List of Katakana Characters

There are 46 katakana characters, some of which can be combined to form even more sounds.

Below is a basic katakana chart with hiragana and rōmaji pronunciations.

To figure out how to read each word, check what row of vowels and what column of consonants they fall under. For example, since カ is under the consonant “k” and on the row “a,” it’s pronounced ka.

Note that Japanese syllabary tables (and Japanese texts in general) are traditionally designed to be read from right to left. However, I’ve arranged the table below from left to right since that’s how English speakers normally read a text. You can get comfortable with reading from right to left as you advance in your Japanese studies.

| k | s | t | n | h | m | l/r**** | w | y | n/m***** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | ア (あ) | カ (か) | サ (さ) | タ (た) | ナ (な) | ハ (は) | マ (ま) | ラ (ら) | ワ (わ) | ヤ (や) | |

| i | イ (い) | キ (き) | シ (し) - shi | チ (ち) chi* | ニ (に) | ヒ (ひ) | ミ (み) | リ (り) | |||

| u | ウ (う) | ク (く) | ス (す) | ツ (つ) tsu** | ヌ (ぬ) | フ (ふ) fu*** | ム (む) | ル (る) | ユ (ゆ) | ||

| e | エ (え) | ケ (け) | セ (せ) | テ (て) | ネ (ね) | ヘ (へ) | メ (め) | レ (れ) | |||

| o | オ (お) | コ (こ) | ソ (そ) | ト (と) | ノ (の) | ホ (ほ) | モ (も) | ロ (ろ) | ヲ (を) | ヨ (よ) | |

| ン (ん) |

*Chi can be used with the “ti” sound, such as in “team” or chimu ( チーム or ちーむ), or the “chi” sound, as in “chicken” or chikin ( チキン or ちきん).

**Tsu can be used for any syllable with the “tu” sound, like “tool” or tsūru ( ツール or つーる).

***Fu is the only f sound in Japanese and can be interchanged with hu. Syllables like fa, fi or fo don’t exist, so when you need to make a word like “family” with katakana, you need to use additional vowel characters: ファミリー (Family) becomes, essentially, fu-ah-mi-ri, for instance.

****Japanese doesn’t have an “l” sound, so it uses “r” for loanwords that have the “l” sound in the original language. For example, “really” would be riarii ( リアリー or りありー).

*****ン (ん) is the only character used at the end of a syllable rather than the beginning.

Here are a few more katakana syllables, which are essentially derivatives of some of the characters shown above. Like in hiragana, adding diacritics to certain characters changes their pronunciation. The diacritics are called dakuten (゛) and handakuten (゜ ).

To illustrate, the “k” sound would become “g,” the “s” would become “z” and so on when diacritics are added. Some syllables use both dakuten and handakuten: for example, ハ (は or ha) can become バ (ば or ba) or パ (ぱ or pa).

| g | z | d | b | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | ガ (が) | ザ (ざ) | ダ (だ) | バ (ば) | パ (ぱ) |

| i | ギ (ぎ) | ジ (じ) | ヂ (ぢ) | ビ (び) | ピ (ぴ) |

| u | グ (ぐ) | ズ (ず) | ヅ (づ) | ブ (ぶ) | プ (ぷ) |

| e | ゲ (げ) | ゼ (ぜ) | デ (で) | ベ (べ) | ペ (ぺ) |

| o | ゴ (ご) | ゾ (ぞ) | ド (ど) | ボ (ぼ) | ポ (ぽ) |

Forming Katakana Words

There are many ways to form katakana words. You can:

- Add a small yu, ya or yo to a katakana syllable that represents a consonant. For example, ketchup becomes ケチャップ (けちゃっぷ) or ke-cha-ppu. Remember to write the “y” sound in a smaller case; otherwise, the pronunciation would be “chi-ya” instead of “cha.”

- Add vowels to a katakana syllable that represents a consonant. The katakana for “Disney” is a good example of this. It would be ディズニー or dizuni (でぃずにー) where the デ (de) and イ (i) sounds are combined to make “di.” As with the previous point, make sure the vowel sound is in a smaller case. Otherwise, ディ (di or ぢ) would become デイ (dei or でい).

- Use an elongation mark to indicate long vowel sounds. For example, the katakana for “taxi” is タクシ ー (たくしー) or takushi where you pronounce the last syllable a bit longer.

- Use a smaller case ツ (tsu) to indicate double consonant sounds that pause or emphasize the preceding consonant. For example, you write ハッピー (happī or はっぴー) for “happy.”

Although you can create your own katakana words if you can’t think of the Japanese word for something, there are many established words you can learn.

200+ Katakana Words to Jump-start Your Vocabulary

I’ve grouped the words below thematically to make them easier to learn—but also to give you a better sense of the kinds of words that often use katakana.

Places

スーパーマーケット

すーぱー まーけっと (sūpāmāketto)

supermarket

コンビニ

こんびに (konbini)

convenience store

レストラン

れすとらん (resutoran)

restaurant

ホテル

ほてる (hoteru)

hotel

マンション

まんしょん (manshon)

condominium

アパート

あぱーと (apāto)

apartment

ビーチ

びーち (bīchi)

beach

パーク

ぱーく (pāku)

park

ショッピングモール

しょっぴんぐもーる (shoppingumōru)

shopping mall

スタジアム

すたじあむ (sutajiamu)

stadium

シネマ

しねま (shinema)

cinema

ギャラリー

ぎゃらりー (gyararī)

gallery

ミュージアム

みゅーじあむ (myūjiamu)

museum

テーマパーク

てーまぱーく (tēma pāku)

theme park

ビューティーサロン

びゅーてぃーさろん (byūtī saron)

beauty salon

カフェ

かふぇ (kafe)

cafe

ギフトショップ

ぎふとしょっぷ (gifuto shoppu)

gift shop

ジム

じむ (jimu)

gym

カラオケボックス

からおけぼっくす (karaoke bokkusu)

karaoke box

Note: “Karaoke” is written in katakana because it actually isn’t an entirely Japanese word, but rather a combination of 空 ( から

) — empty and the loanword オーケストラ

(おーけすとら) — orchestra.

ライブハウス

らいぶはうす (raibu hausu)

live house

カジノ

かじの (kajino)

casino

クラブ

くらぶ (kurabu)

club

カルチャーセンター

かるちゃーせんたー (karuchāsentaー)

cultural center

ギャンブル場

ぎゃんぶるば (gyanburu ba)

gambling venue

スパ

すぱ (supa)

spa

プール

ぷーる (pūru)

pool

サウナ

さうな (sauna)

sauna

プラザ

ぷらざ (puraza)

plaza

Geographical Locations

ヨーロッパ

よーろっぱ (yōroppa)

Europe

アメリカ

あめりか (amerika)

America

イタリア

いたりあ (itaria)

Italy

オランダ

おらんだ (oranda)

Holland

カナダ

かなだ (kanada)

Canada

スペイン

すぺいん (supein)

Spain

フランス

ふらんす (furansu)

France

ロシア

ろしあ (roshia)

Russia

アフリカ

あふりか (afurika)

Africa

アジア

あじあ (ajia)

Asia

オーストラリア

おーすとらりあ (ōsutoraria)

Australia

サハラ

さはら (sahara)

Sahara Desert

カリブ

かりぶ (karibu)

Caribbean

コンゴ

こんご (kongo)

Congo

アンデス

あんです (andesu)

Andes

ニュージーランド

にゅーじーらんど (nyūjīrando)

New Zealand

モンゴル

もんごる (mongoru)

Mongolia

モロッコ

もろっこ (morokko)

Morocco

カンボジア

かんぼじあ (kanbojia)

Cambodia

マダガスカル

まだがすかる (madagasukaru)

Madagascar

ベトナム

べとなむ (betonamu)

Vietnam

ケニア

けにあ (kenia)

Kenya

アルゼンチン

あるぜんちん (aruzenchin)

Argentina

タンザニア

たんざにあ (tanzania)

Tanzania

ブラジル

ぶらじる (burajiru)

Brazil

ウルグアイ

うるぐあい (uruguai)

Uruguay

Holidays

クリスマス

くりすます (kurisumasu)

Christmas

ハロウィン

はろうぃん (harowin)

Halloween

バースデー

ばーすでー (bāsudē)

birthday

イースター

いーすたー (īsutā)

Easter

サンクスギビングデー

さんくすぎびんぐでー (sankusugibingudē)

Thanksgiving Day

アースデー

あーすでー (āsudē)

Earth Day

バレンタイン

ばれんたいん (barentain)

Valentine’s Day

ゴールデンウィーク

ごーるでんうぃーく (gōruden wīku)

Golden Week (a series of holidays in late April and early May in Japan)

シルバーウィーク

しるばーうぃーく (shirubā wīku)

Silver Week (a series of holidays in September in Japan)

ホワイトデー

ほわいとでー (howaito dē)

White Day (a day when men give gifts to women in return for Valentine’s Day)

Food

ハンバーガー

はんばーがー (hanbāgā)

hamburger

チョコレート

ちょこれーと (chokorēto)

chocolate

ピザ

ぴざ (piza)

pizza

カレー

かれー (karē)

curry

アイスクリーム

あいすくりーむ (aisukurīmu)

ice cream

フライドポテト

ふらいど ぽてと (furaidopoteto)

French fries

ケーキ

けーき (kēki)

cake

サンドイッチ

さんどいっち (sandoitchi)

sandwich

スパゲッティ

すぱげってぃ (supagetti)

spaghetti

チーズ

ちーず (chīzu)

cheese

ラーメン

らーめん (rāmen)

ramen

カツ丼

かつどん (katsudon)

katsudon (breaded and deep-fried pork cutlet served over rice)

オムライス

おむらいす (omuraisu)

omurice (omelette served over rice)

カルビ

かるび (karubi)

kalbi (Korean-style marinated beef short ribs)

タコス

たこす (takosu)

tacos

サラダ

さらだ (sarada)

salad

テンプラ

てんぷら (tenpura)

tempura (battered and deep-fried seafood or vegetables)

シーフード

しーふーど (shīfūdo)

seafood

カニ

かに (kani)

crab

エビ

えび (ebi)

shrimp

カツオ

かつお (katsuo)

bonito (type of fish)

ユッケ

ゆっけ (yukke)

yukhoe (Korean dish made with raw beef)

ウナギ

うなぎ (unagi)

eel

ホタテ

ほたて (hotate)

scallop

イクラ

いくら (ikura)

salmon roe

トマト

とまと (tomato)

tomato

メロン

めろん (meron)

melon

コーヒー

こーひー (kōhī)

coffee

ジュース

じゅーす (jūsu)

juice

ビール

びーる (bīru)

beer

ダイエット

だいえっと (daietto)

diet

Sports

アメリカンフットボール / アメフト

あめりかんふっとぼーる / あめふと (amerikan futtobōru / amefuto)

American football

バスケットボール / バスケ

ばすけっとぼーる / ばすけ (basukettobōru / basuke)

basketball

チアリーダー

ちありーだー (chiarīdā)

cheerleader

サッカー

さっかー (sakkā)

soccer

ゴルフ

ごるふ (gorufu)

golf

ラグビー

らぐびー (ragubī)

rugby

テニス

てにす (tenisu)

tennis

バドミントン

ばどみんとん (badominton)

badminton

ソフトボール

そふとぼーる (sofutobōru)

softball

ボクシング

ぼくしんぐ (bokushingu)

boxing

カヌー

かぬー (kanū)

canoe

アーチェリー

あーちぇりー (ācherī)

archery

スイミング

すいみんぐ (suimingu)

swimming

サーフィン

さーふぃん (sāfin)

surfing

スケートボード

すけーとぼーど (skētobōdo)

skateboarding

ボルダリング

ぼるだりんぐ (borudaringu)

bouldering

スキー

すきー (sukī)

skiing

スノーボード

すのーぼーど (sunōbōdo)

snowboarding

フィギュアスケート

ふぃぎゅあすけーと (figyua sukēto)

figure skating

バレーボール

ばれーぼーる (barēbōru)

volleyball

ボウリング

ぼうりんぐ (bōringu)

bowling

アーティスティックスイミング

あーてぃすてぃっくすいみんぐ (ātisutikkusuimingu)

artistic swimming

スポーツカー

すぽーつかー (supōtsukā)

sports car

Technology

マスコミ

ますこみ (masukomi)

mass media or mass communications

カメラ

かめら (kamera)

camera

テレビ

てれび (terebi)

television

アニメ

あにめ (anime)

animation

Note: Outside of Japan the word “anime” is used for a particular form of Japanese animation, but in Japan the word is used to describe all forms of animation.

エスカレーター

えすかれーたー (esukarētā)

escalator

バイク

ばいく (baiku)

motorbike

アイテム

あいてむ (aitemu)

item (especially in a video game)

ミッション

みっしょん (misshon)

mission (especially in a videogame)

コンピューター

こんぴゅーたー (konpyūtā)

computer

スマートフォン

すまーとふぉん (sumātofon)

smartphone

インターネット

いんたーねっと (intānetto)

internet

デジタル

でじたる (dejitaru)

digital

ロボット

ろぼっと (robotto)

robot

ソフトウェア

そふとうぇあ (sofutowea)

software

ハードウェア

はーどうぇあ (hādouea)

hardware

インターフェース

いんたーふぇーす (intāfēsu)

interface

ガジェット

がじぇっと (gajetto)

gadget

バイオテクノロジー

ばいおてくのろじー (baiotekunorojī)

biotechnology

クラウド

くらうど (kuraudo)

cloud

センサー

せんさー (sensā)

sensor

ロケーション

ろけーしょん (rokēshon)

location

アルゴリズム

あるごりずむ (arugorizumu)

algorithm

ネットワーク

ねっとわーく (nettowāku)

network

データ

でーた (dēta)

data

プログラミング

ぷろぐらみんぐ (puroguramingu)

programming

ロボティクス

ろぼてぃくす (robotikusu)

robotics

バイオメトリクス

ばいおめとりくす (baiometorikusu)

biometrics

アプリ

あぷり (apuri)

app

リモコン

りもこん (rimokon)

remote control

モード

もーど (mōdo)

mode

People and Names

モーツァルト

もーつぁると (mōtsuaruto)

Mozart

ドナルド・トランプ

どなるど・とらんぷ (donarudo toranpu)

Donald Trump

バラク・オバマ

ばらく・おばま (baraku obama)

Barack Obama

ブリトニー・スピアーズ

ぶりとにー・すぴあーず (buritonī supiāzu)

Britney Spears

オプラ

おぷら (opura)

Oprah

エルビス・プレスリ

えるびす・ぷれすりー (erubuisu puresurī)

Elvis Presley

キム・カーダシアン

きむ・かーだしあん (kimu kādashian)

Kim Kardashian

ビヨンセ

びよんせ (biyonse)

Beyoncé

ブラッド・ピット

ぶらっど・ぴっと (buraddo pitto)

Brad Pitt

オードリー・ヘップバーン

おーどりー・へっぷばーん (ōdorī heppubān)

Audrey Hepburn

マリリン・モンロー

まりりん・もんろー (maririn monrō)

Marilyn Monroe

ウィル・スミス

うぃる・すみす (wiru sumisu)

Will Smith

アルフレッド・ヒッチコック

あるふれっど・ひっちこっく (arufureddo hitchikokku)

Alfred Hitchcock

マイケル・ジャクソン

まいける・じゃくそん (maikeru jakuson)

Michael Jackson

リアーナ

りあーな (riāna)

Rihanna

ジャスティン・ビーバー

じゃすてぃん・びーばー (jasutin bībā)

Justin Bieber

レディー・ガガ

れでぃー・がが (redī gaga)

Lady Gaga

アンジェリーナ・ジョリー

あんじぇりーな・じょりー (anjīrīna jorī)

Angelina Jolie

ブルース・リー

ぶるーす・りー (burūsu rī)

Bruce Lee

デヴィッド・ボウイ

でヴぃっど・ぼうい (devuiddo boui)

David Bowie

ジョニー・デップ

じょにー・でっぷ (jonī deppu)

Johnny Depp

カミラ・カベロ

かみら・かべろ (kamira kabero)

Camila Cabello

ブルノ・マーズ

ぶるの・まーず (buruno māzu)

Bruno Mars

ジョージ・クルーニー

じょーじ・くるーにー (jōji kurūnī)

George Clooney

Other Words

アイドル

あいどる (aidoru)

idol or pop star

ヒットソング

ひっとそんぐ (hitto songu)

hit song

フリーター

ふりーたー (furītā)

part-timer or freeter

メーク

めーく (mēku)

makeup/cosmetics

ツアー

つあー (tsuā)

tour

サラリーマン

さらりーまん (sararīman)

salaryman

ビジネスマン

びじねすまん (bijinesuman)

businessman

Note: “Businessman” is sometimes used interchangeably with “salaryman,” although “businessman” has a broader scope than “male white-collar employee”

オフィスレディ

おふぃすれでぃ (ofisu redi)

office lady

Note: “Office lady” is often abbreviated to “OL” ( オーエル

or おーえる (ōeru))

ソファ

そふぁ (sofa)

sofa

アフターサービス

あふたーさーびす (afutā sābisu)

after service a.k.a. customer service or after-the-sale service

アンサー

あんさー (ansā)

answer

アルコール

あるこーる (arukōru)

alcohol

フリーサイズ

ふりーさいず (furī saizu)

free size, a.k.a. “one size fits all”

ドキュメント

どきゅめんと (dokyumento)

document

アドバイス

あどばいす (adobaisu)

advice

トラブル

とらぶる (toraburu)

trouble

シナリオ

しなりお (shinario)

scenario

メモ

めも (memo)

memo

タイム

たいむ (taimu)

time

ボリューム

ぼりゅーむ (boryūmu)

volume

テーマ

てーま (tēma)

theme

パートナー

ぱーとなー (pātonā)

partner

スタイル

すたいる (sutairu)

style

クリア

くりあ (kuria)

clear

ファッション

ふぁっしょん (fasshon)

fashion

ミュージック

みゅーじっく (myūjikku)

music

ノート

のーと (nōto)

notebook

ダンス

だんす (dansu)

dance

グラス

ぐらす (gurasu)

glass

Note: グラス is also the katakana for “grass.” Sometimes in Japanese, context is everything!

ボーナス

ぼーなす (bōnasu)

bonus

Important Things to Note About Katakana

So, when do you use the katakana version of a word?

- Stand-ins for words that don’t exist in Japanese: For example, since there’s no word for “supermarket” in Japanese, katakana must be used. In the same vein, there are also Japanese words that don’t exist in other languages.

- Context: Perhaps you’re speaking to a beginner Japanese learner and katakana is a little easier for them to understand. Maybe other speakers in a group conversation are using a lot of katakana. There’s no right or wrong: just go with the flow!

It’s also worth noting that some katakana words are shortened, like スーパーマーケット (すーぱー まーけっと) — sūpāmāketto (supermarket), which is often shortened to スーパー (すーぱー) — sūpā. Japanese has its own slang just like English does.

Finally, keep in mind that some loan words come from languages other than English, while other words have odd origins. For instance, the word バイキング (ばいきんぐ) — Baikingu might sound like “Viking” or “biking,” but it actually means “buffet-style” in Japanese. Likewise, ドイツ (どいつ) — Germany is pronounced Doitsu to reflect the German word for the country, Deutschland.

There are actually quite a lot of weird katakana words like this with very interesting and somewhat comical origins. So, just remember: Things aren’t always what they look like:

6 Japanese Words Everyone Thinks They Understand (But Don’t)

1. テンション (tenshon)

At first glance, this looks like it may mean “tension” or “tense,” as in “the tension in the 職員室 (shokuinshitsu, teacher’s staff room) was palpable after Takashi admitted he was the one who had peed in the coffee machine.”

However, in Japanese テンション takes on quite the opposite meaning, typically seen in the phrase テンションが高い!(tenshon ga takai!). This means that “he/she is really excited” or “in high spirits.” This phrase is synonymous with 盛り上がっている (moriagatteiru) “to be pumped/charged up.”

There are a few theories behind how it came to take on this positive nuance, the most plausible of which comes from the music world.

In constructing musical chords, jazz musicians will frequently employ “tension notes” to add character and depth to a certain chord. Japanese musicians would speak to each other saying “テンションをあげよう!” (tenshon oh ageyou!) or “let’s add more tension (notes).” Fans would interpret this to mean 盛り上げよう!(moriageyou) or “let’s really get things pumping!”

Example:

たかしはテンションが高いね!入学試験(nyuugakushiken)を合格(goukaku)したかな?

Takashi is really excited! I wonder if he passed his college entrance exams.

2. スナック (snakku)

A スナック in Japanese is not a delicious treat one may eat in the afternoon to tide over their hunger until dinner. That type of snack would be 軽食 (keishoku). No, a スナック in Japanese is a shortening of the word スナックバー (snakkubaa), which is a type of hostess bar which serves alcohol and small appetizers and employs younger girls to talk to and flirt with their all-male customer base.

Typically these establishments charge a rather high hourly fee for the service of just chatting with the younger girls, but snakku bars usually don’t offer “extra-curricular” (sexual) services. These services are more common at places called キャバクラ (kyabakura).

Example:

After a drinking party…

A: 何か、飲み足りない(nomitarinai)なぁ。キャバクラでも行かない?

B: いやぁ、行き着きのスナックに寄りたい。一緒に来ない?

A: I feel like drinking some more. Want to go to a kyabakura?

B: Nah, I’d like to drop by the snakku I usually go to. Want to come with?

3. カンニング (kanningu)

Think back to high school. Were you ever guilty of taking a peek over at your neighbor’s answer sheet? If so, カンニングした!

カンニング comes from the English word “cunning,” and it isn’t too far off from its English origin. However, keep in mind that it’s a noun and only means “cheating.” It cannot be used as an adjective. To say “cunning” as an adjective, you can use the popular word ずるい (zurui) or the less often heard but still valid word 狡猾 (koukatsu).

カンニング is said to have entered Japanese during the early Meiji Era among students who were looking to pull fast ones on their professors. Rather than outright discuss cheating, they would refer to cheating as カンニング as a secret word, to mask what they were actually discussing.

Example:

A: のぶは数学(suugaku)の試験(shiken)を受かったのか?!あのバカはいったいどうやってできた?!

B: あの天才(tennsai)のみちこの回答用紙(kaitouyoushi)を覗き見(nozokimi)して、カンニングしたらしい。

A: Nobu passed the Math exam?! How in the world did that idiot do it?!

B: I heard he cheated, peeking at that genius Michiko’s answer sheet.

4. アメリカン・ジョーク (amerikan jooku)

Who can’t go for a good old American joke every once in a while? The Japanese, that’s who. This is because in Japanese, an アメリカン・ジョーク is not a “joke made by and American” or a “joke about Americans,” rather, it’s a joke that just plain old sucks (to the Japanese at least).

Humor is probably the most difficult aspect of a language to translate into another language. The origins of アメリカン・ジョーク can be found in the fact that a specific subset of jokes told in America (and other countries too, to be fair) require the listener to connect the dots and figure out for themselves why something is funny.

Listeners have to “intuit” their way through how seemingly unrelated pieces of information can be put together in a funny way. Unfortunately, the Japanese just don’t tell jokes this way, and thus, when translating this type of humor into Japanese, the punch line is often lost on listeners.

Take this exchange between A and B as A tells a joke to B (keep in mind, this is NOT a Japanese joke. Don’t try to use it yourself unless you are ready to face a room full of cold stares).

Example:

A: 2頭(tou)のクジラはバーで飲んでいる。1頭はもう1頭に向かってこう言う(Aはクジラの鳴き声(nakigoe)を2分ほどマネをする)。そして、そのもう1頭は最初(saisho)のクジラに向けて答えた。「お前、酔ってる(yotteru)ね」

B: (笑わずに真剣(shinnken)な顔をしている)わかんないよ。アメリカン・ジョークだね。

A: Two whales are drinking in a bar. One whale says to the other… (speaker A imitates a whale song for 2 minutes). Then, the other whale looks at the first and answers “Dude, I think you’re drunk.”

B: (not-laughing and with a serious expression). I don’t get it. That’s such an American joke.

*Note: アメリカン・ジョーク are not strictly limited to being told by Americans. There are plenty of British, Australian and people of all nationalities who, to their chagrin, have been lumped in with their American counterparts as purveyors of アメリカン・ジョークs.

5. マイペース (maipeesu)

マイペース most likely entered Japanese through the world of marathon running. A runner might say, “私はいつもマイペースで走っています” (watashi wa itsumo maipeesu de hashitte imasu) meaning “I always run at my (own) pace.”

Runners who run at “マイペース” try not to get drawn by other runners into running too hard and too fast, tiring themselves out before the end of the race.

However, this original meaning of マイペース was later generalized to mean someone who “lives life at their own pace.” Someone who is マイペース generally won’t be rushed to do things, or has a tendency to “do things their own way.”

Example:

A: この仕事をなみちゃんい任せよう(makaseyou)と思っていますが、いかがでしょうか?

B: いや、なみはすごくマイペースで、これはしっかりした形でしないなりません。

A: I was thinking of leaving this work to Nami, what do you think?

B: Nah, Nami has her own way of doing things, and this needs to be done according to standard.

6. マイ… (mai…)

マイ is a particularly odd duck of a word. Possibly having originated as an expansion from the previous example マイペース, マイ is used as a prefix to describe something as “one’s own,” can be attached to almost anything that one owns.

Thus マイカー、マイハウス、マイ犬 respectively mean “my car,” “my house,” and “my dog.” A popular usage of this is マイ箸(maihashi), or “my chopsticks,” specifically used for chopsticks that one carries around with them so they don’t have to waste lots of 割り箸 (waribashi) or wooden, disposable chopsticks.

However, the use of マイ is often a source of confusion for Japanese learners, as it does not specifically mean “my,” but rather means “one’s own.” Take a look at the following example:

Example:

A: マイボールペン持っていますか?

B: いやぁ、忘れちゃったな。あなたのマイボールペンを借りてもいいですか?

A: Do you have your own pen?

B: Ahh, it looks like I forgot it. Could I borrow yours?

When speaker A asks speaker B if he has マイボールペン, he is not asking if speaker B has speaker A’s pen (as one might assume by the prefix マイ), but rather, is asking if speaker B has his own pen. Thus, to clarify, speaker B may want to ask speaker A if A has “あなたのマイボールペン,” or, in English, if A has a pen that belongs to A.

Another great example comes from the sports world. Playing basketball or soccer, when the ball goes out of bounds players will often frenzy, screaming “it’s our ball!” to claim who should get possession. Possession of the ball in this instance in Japanese is called マイボール.

Example:

(a basketball is knocked out of bounds during a game between two people)

A: よし、マイボールだ。

B: 違うでしょう!お前は最後に触った(sawatta)だろう!私のマイボールだぞ!

A: 分かった、分かった。触ってないと思うけど、今回はお前のマイボールとして許す(yurusu)。でも今度は私のマイボールになる。

A: Alright, it’s my ball.

B: No way! You touched it last! It’s my ball!

A: Okay, okay. I don’t think I touched it, but I’ll let you take it this time. But next time it’ll be my ball.

Using and interpreting マイ correctly may be confusing at first, but just remember that when people say “マイ” they could be referring to something that is theirs, or asking you about something that is yours.

Isn’t katakana such an interesting syllabary?

If you want to learn more Japanese words, check out these posts on the ones that are cute, useful and food-related.

You can also hop on a language learning platform like FluentU, which showcases immersive videos complete with interactive subtitles.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Good luck! Or rather, グッドラック ! (ぐっどらっく) — Guddo rakku!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU.

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

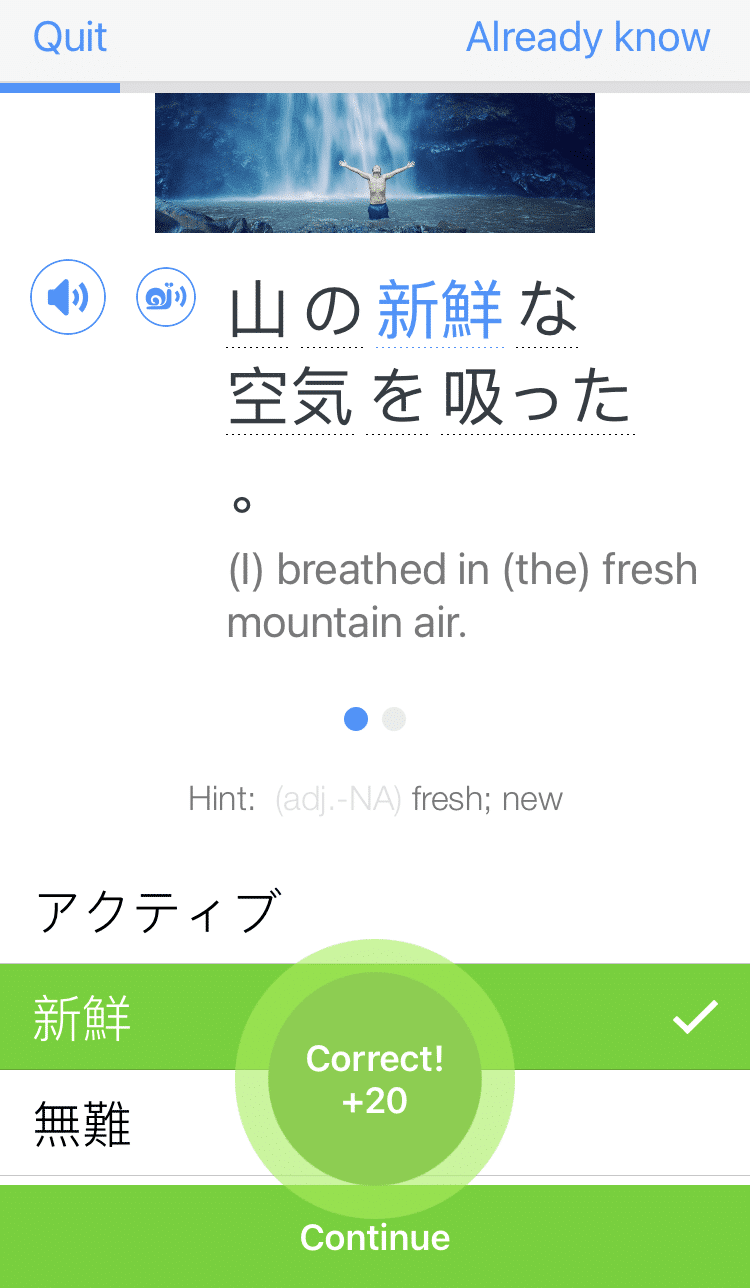

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)