A Guide to the Portuguese Past Tenses

Brazilian culture has a bit of an obsession with the here and now, but speaking Portuguese also means hearing and telling stories of things that have already occurred.

And to do that, you’ll need to employ some of the various Portuguese past tenses.

In this post, we’ll focus on the key past tenses for upper-beginner to upper-intermediate Portuguese learners. These will help you talk about events at past points in time, set the scene of past situations and discuss hypothetical pasts.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

The Preterite Indicative Tense

Usage: Discusses limited, completed actions

The first past tense that most Portuguese learners tackle is the preterite indicative, which is used to describe simple, closed-off past events.

The regular verb conjugations are as follows:

| -AR Verb Falar (To Speak) | -ER Verb Beber (To Drink) | -IR Verb Dormir (To Sleep) |

|---|---|---|

| Eu falei

(I spoke) | Eu bebi

(I drank) | Eu dormi

(I slept) |

| Você/Ele/Ela falou

(You/He/She spoke) | Você/Ele/Ela bebeu

(You/He/She drank) | Você/Ele/Ela dormiu

(You/He/She slept) |

| Nós falamos

(We spoke) | Nós bebemos

(We drank) | Nós dormimos

(We slept) |

| Vocês/Eles/Elas falaram

(You all / They spoke) | Vocês/Eles/Elas beberam

(You all / They drank) | Vocês/Eles/Elas dormiram

(You all / They slept) |

Pop quiz: Can you spot which of the above conjugations is exactly the same as its present tense version?

Answer: The nós forms.

So we say, for example, ontem bebemos cachaça (we drank cachaça yesterday) and use the same verbal form to say bebemos cachaça todos os dias (we drink cachaça every day). Context is needed to know whether the past or present is intended.

The preterite is the Portuguese tense for talking about single, completed actions or those that were repeated but happened in discreet, completed time units in the speaker’s mind. As usual in Portuguese, the pronouns are omitted unless necessary for emphasis or clarity; the conjugations are otherwise enough to indicate who did what.

Here are some examples with regular verbs:

Falei com ela às 10:00 da manhã.

(I spoke with her at 10:00 a.m.)

Eles beberam café sem açúcar essa manhã.

(They drank coffee without sugar this morning.)

Adorei o show.

(I loved the concert.)

Once you get the hang of the regular verbs, brace yourself, because things are about to get weird.

Conjugating Irregular Verbs

The most-used verbs in Portuguese are irregular—worn down and warped by generations of tongues lapping lazily at them—and this is particularly true with preterite conjugations.

These irregular preterite verb conjugations are incredibly important to learn well not just because you need them so often, but also because they’re useful as you move on to study the future and imperfect subjunctive forms, whose irregular conjugations can be derived from your knowledge of the preterite indicative.

Here are a few of the most important ones to get you started. You’ll want to memorize all of them!

Saber

Meaning: to know, but in the preterite means to have heard about something/learned/found out

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| Eu soube | I heard about something I learned I found out |

| Você/Ele/Ela soube | You/He/She heard about something You/He/She learned You/He/She found out |

| Nós soubemos | We heard about something We learned We found out |

| Vocês/Eles/Elas souberam | You all / They heard about something You all / They learned You all / They found out |

Example:

Eu soube que eles estão ficando.

(I heard that they’re dating.)

Dizer

Meaning: to say/tell

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| Eu disse | I said |

| Você/Ele/Ela disse | You/He/She said |

| Nós dissemos | We said |

| Vocês/Eles/Elas disseram | You all / They said |

Example:

Dissemos tudo que pensamos.

(We said everything we thought.)

Pôr

Meaning: to put

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| Eu pus | I put |

| Você/Ele/Ela pôs | You/He/She put |

| Nós pusemos | We put |

| Vocês/Eles/Elas puseram | You all / They put |

Example:

Pusemos os pratos na mesa.

(We put the plates on the table.)

Both pôr and the verb colocar can be used to say “to put” in Brazilian Portuguese. However, it’s particularly useful to know pôr, as its compounds ( compor “to compose,” opor-se “to oppose,” etc.) have the same conjugations.

Meaning: to give

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| Eu dei | I gave |

| Você/Ele/Ela deu | You/He/She gave |

| Nós demos | We gave |

| Vocês/Eles/Elas deram | You all / They gave |

Example:

Eles me deram uma mochila chique. (They gave me a fancy backpack.)

Estar

Meaning: to be (temporary)

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| Eu estive | I was |

| Você/Ele/Ela esteve | You/He/She were/was |

| Nós estivemos | We were |

| Vocês/Eles/Elas estiveram | You all / They were |

Example:

Eu já estive cinco vezes no Brasil!

(I was in Brazil five times already!)

Ser ; Ir

Meaning: to be (characteristic); to go

These two verbs are different in plenty of tenses but share the exact same preterite indicative forms.

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| Eu fui | I was I went |

| Você/Ele/Ela foi | You/He/She were/was You/He/She went |

| Nós fomos | We were We went |

| Vocês/Eles/Elas foram | You all / They were You all / They went |

Examples:

Fui ao Brasil em maio.

(I went to Brazil in May.)

Foi um dia de sacanagem.

(It was a day of messing around/naughtiness.)

The Imperfect Tense

Usage: Sets the scene for hazy, unfinished past conditions

The Portuguese solution for setting scenes and talking about the way things used to be is the imperfect. It often translates into English with the constructions “was …ing” and “used to…”

The regular conjugations are as follows. Notice that the first- and third-person singular forms are always identical.

Verbs ending in -ar, like falar (to speak):

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| Eu/Você/Ele/Ela falava | I/You/He/She was/were speaking I/You/He/She used to speak |

| Nós falávamos | We were speaking We used to speak |

| Vocês/Eles/Elas falavam | You all/They were speaking You all/They used to speak |

Verbs ending in -er, like beber (to drink):

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| Eu/Você/Ele/Ela bebia | I/You/He/She was/were drinking I/You/He/She used to drink |

| Nós bebíamos | We were drinking We used to drink |

| Vocês/Eles/Elas bebiam | You all / They were drinking You all / They used to drink |

Verbs ending in -ir, like dormir (to sleep):

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| Eu/Você/Ele/Ela dormia | I/You/He/She was/were sleeping I/You/He/She used to sleep |

| Nós dormíamos | We were sleeping We used to sleep |

| Vocês/Eles/Elas dormiam | You all / They were sleeping You all / They used to sleep |

Notice that -er and -ir verbs have identical endings in this tense.

The imperfect indicative is pretty regular, but an important irregular imperfect verb to know is ser (to be):

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| Eu/Você/Ele/Ela era | I/You/He/She was/were I/You/He/She used to be |

| Nós éramos | We were We used to be |

| Vocês/Eles/Elas eram | You all / They were You all / They used to be |

The imperfect vs. the preterite

To start employing these conjugations, it’s helpful to keep in mind how this tense differs from the preterite. Recall that the preterite was for talking about completed events seen at a point in time. The imperfect, on the other hand, is a bit more wishy-washy about when things started and especially when they ended.

I’ve got some funny little characters on my keyboard that get the preterite and imperfect contrasts across even better than my most well-crafted verbiage.

Preterite: •

Imperfect: ~

Does it make sense now?

Let’s see that idea in action. We can contrast the following two sentences:

Preterite:

Eu pedi conselhos para ela sobre o Rio.

(I asked her for advice for Rio.)

Imperfect:

Eu sempre pedia conselhos para ela sobre o Rio.

(I used to always ask her for advice for Rio.)

Let’s dig a little more specifically into more uses that trigger the imperfect. The key one is when we want to talk about how things used to be.

Eu sempre trazia um laptop para trabalhar nas férias.

(I used to always bring a laptop to work on vacation.)

Ele era vegetariano quando era jovem.

(He was a vegetarian when he was young.)

If you’re launching into a story, you usually set the scene first, which again calls up the imperfect.

A praia estava vazia e o sol brilhava no mar.

(The beach was empty and the sun was shining on the sea.)

And you can use the imperfect to set a mini-scene for what was going on when—bang!—a pointed, preterite thing happened.

Andava de bicicleta quando ela ligou.

(I was biking when she called.)

The Progressive Imperfect Tense

Usage: Discusses what was occurring during a past event

You can employ the imperfect form of estar (to be) plus the gerund in Brazilian Portuguese to talk about something that was ongoing/continuing in the past. This is particularly common in speech.

Estávamos indo à praia quando começou a chover.

(We were going to the beach when it started to rain.)

Por que você estava xavecando a gente na pista de dança?

(Why were you flirting with us on the dance floor?)

While that’s fine for speech, it’s perhaps more common to write the previous sentences using simply the imperfect ( Íamos na praia… xavecava… ).

The Perfect Tenses in Spoken Brazilian Portuguese

Brazilians aren’t big users of past participles, but they do occur in the language and need to be learned. The regular past participles are formed by knocking off the -ar, -er or -ir from the end of the verb and replacing them with -ado, -ido or –ido, respectively.

So for three regular verbs, that would make:

There are also irregular participles. Some of the most common are:

You can use the past participles with the present tense of ter (to have) as an auxiliary to talk about what you “have been doing.” This corresponds to the English perfect continuous and not, as you might expect, the perfect simple for talking about what you “have done.”

So, for example:

Tenho viajado muito no Brasil ultimamente.

(I’ve been traveling in Brazil a lot recently.)

Ele tem visto muitas séries na Netflix desde que ficou doente.

(He’s been watching a lot of shows on Netflix since he became sick.)

Note that unlike in English, we don’t use this form for talking about how long something’s been going on; we instead use the present tense and faz plus the time period.

Ele trabalha para mim faz um ano.

(He’s been working for me for one year.)

If you combine the past participles with the imperfect tense of ter, you can form the pluperfect for talking about pasts before the past. For example:

Eu tinha dito para ele levar um guarda-chuva para São Paulo! Mas não me ouviu, e ficou todo molhado.

(I’d told him to take an umbrella to São Paulo! But he didn’t listen to me, and ended up soaked.)

Até o ano passado, eles nunca tinham visto o mar.

(Until last year, they’d never seen the sea.)

Less commonly, in formal writing, you can use haver as the auxiliary verb in the pluperfect.

Eles não haviam votado nas eleições, mas se queixaram mesmo assim.

(They hadn’t voted in the elections, but they complained anyway.)

You can also use ter in the future and conditional tenses as the auxiliary verb followed by the past participle to talk about what will have happened or would’ve happened, respectively.

Vai ver, amanhã teremos acabado todo o trampo!

*

(You’ll see, tomorrow we’ll have finished all of the work!)

*Trampo—both the word and the obsession—are quintessentially São Paulo. I’ve given this example to show the future tense, but note that in spoken language it would be more common to use the spoken construction with ir for the future: Vamos ter acabado .

Teria ido ao Rio se soubesse que você estaria aí.

(I would’ve gone to Rio if I’d known that you’d be there.)

The Past Subjunctive

Usage: Talks about desires and theories of the past

If you’ve studied the subjunctive mood in the present tense, you already have an idea of what it’s for: hypotheticals, feelings and opinions about actions and imaginary situations. The same concepts also apply to the subjunctive mood as used with past tenses.

You can recognize the imperfect subjunctive forms, as they tend to end with -sse, -ssemos or -ssem. Both the regular and irregular verb conjugations need to be learned, but when you’re starting out it’s enough at first to just be able to recognize them.

Eu queria que você dançasse comigo.

(I wanted you to dance with me.)

Ganhou o concurso ainda que não estivesse usando sapatos de dança.

(He won the contest even though he wasn’t wearing dance shoes.)

Embora fosse longe, fomos ver o espetáculo.

(Even though it was far, we went to see the show.)

The subjunctive forms of ter can also be used with past participles for hypotheticals or opinions about past situations.

Que chato que você tenha passado tanto tempo com ele.

(How annoying that you were spending so much time with him.)

Eles duvidam que tivéssemos visitado as cachoeiras do Iguaçu.

(They doubt that we visited the Iguaçu falls.)

Yes, it’s kind of a pain to work out the proper subjunctive in the past tenses—and even Brazilians seem to agree and so the mood is often avoided in speech, especially with certain constructions. So while you’ll definitely still hear the subjunctive past tenses, you’re also likely to hear the indicative replacing them, even when they “should” be used. For instance:

Que chato que você passou tanto tempo com ele.

(How annoying that you were spending so much time with him.)

How to Study Portuguese Past Tenses

No matter how ambitious your learning plan is, these tenses aren’t to be devoured all in one sitting.

In fact, each tense requires quite a bit of study on its own. You might, for example, spend a study session on just -ar verbs in the preterite and practice writing out sentences that relate to your life and past events with those verbs.

Once you’ve got a firm handle on that, put your notes away and see if you can use those same verbs to tell a teacher or language exchange partner a story. Only when you’ve really mastered that will you be ready to move on to other verbs in the preterite, and beyond.

A good textbook can also help you study, as well as one-on-one learning classes and exposure to authentic uses in Portuguese podcasts, videos and language exchanges.

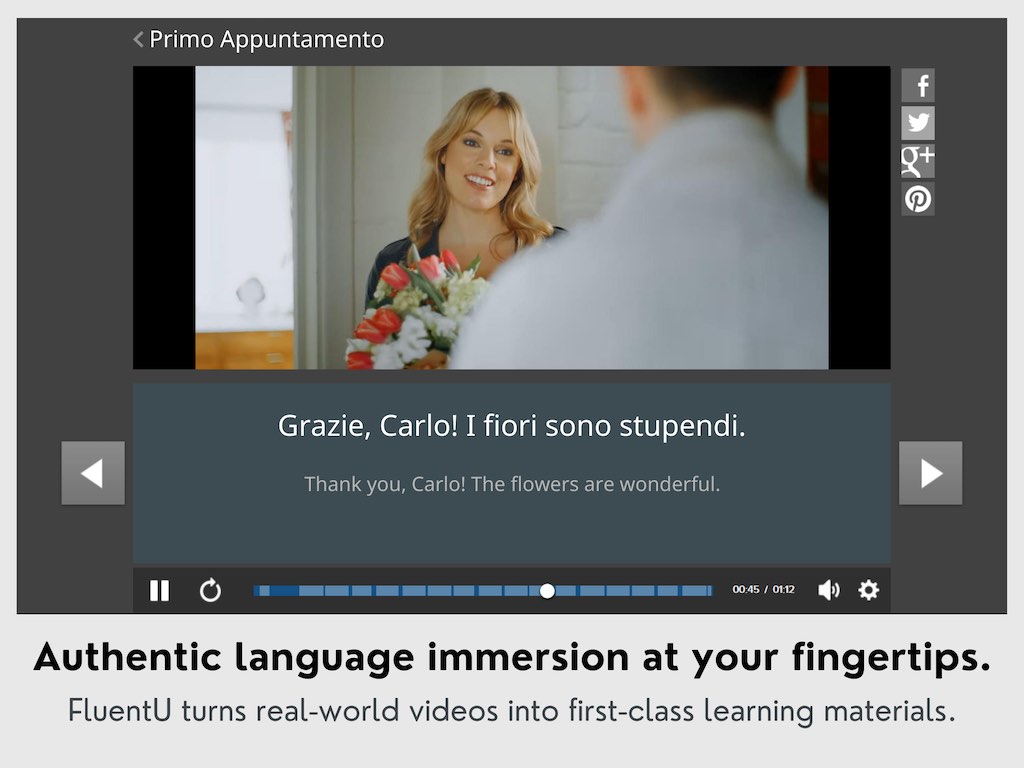

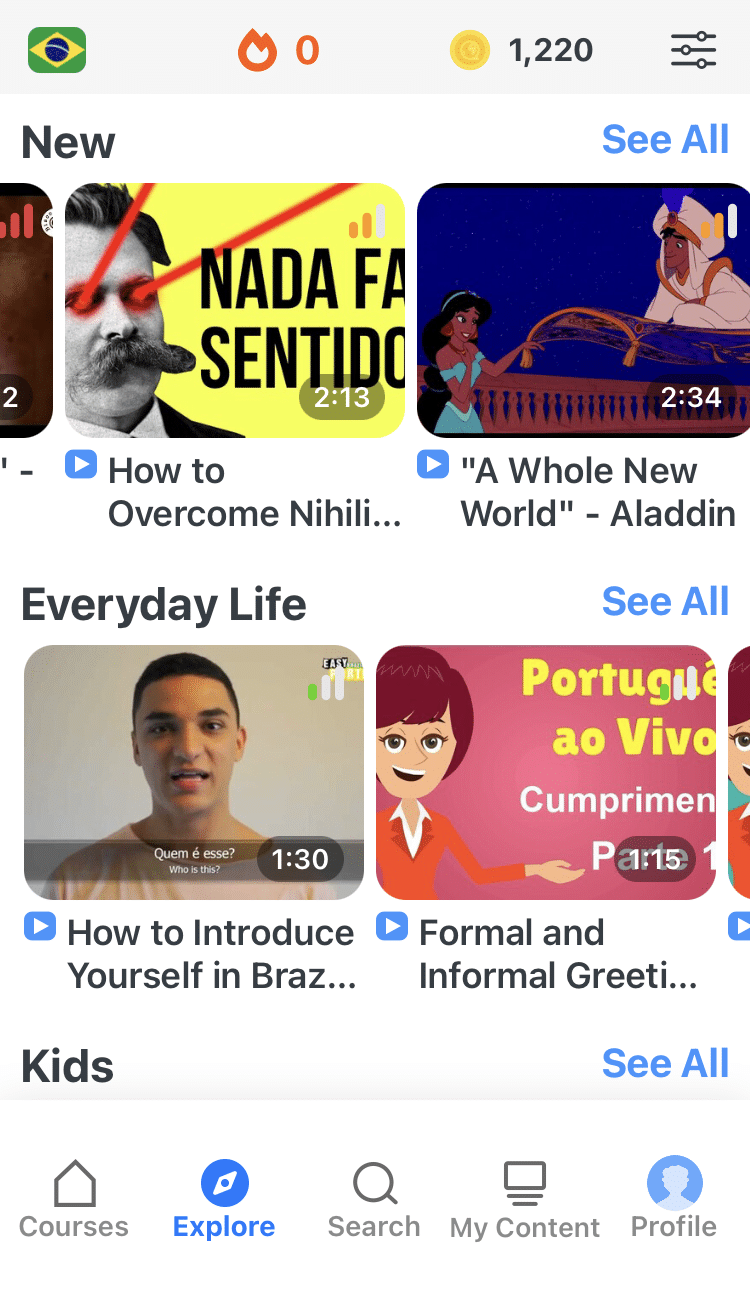

Alternatively, you can pick my favorite option for learning: Pack up and head to a Portuguese-speaking land, and start chatting with native speakers. But when that’s not an option, immersion programs like FluentU work as a great alternative.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Click here to check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

Now that you’ve studied an overview of the past tenses in Portuguese, you can start talking about your past and understanding the pasts of others.

Keep practicing these tenses and with any luck, doing the work now will give you opportunities for great conversations in the future.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

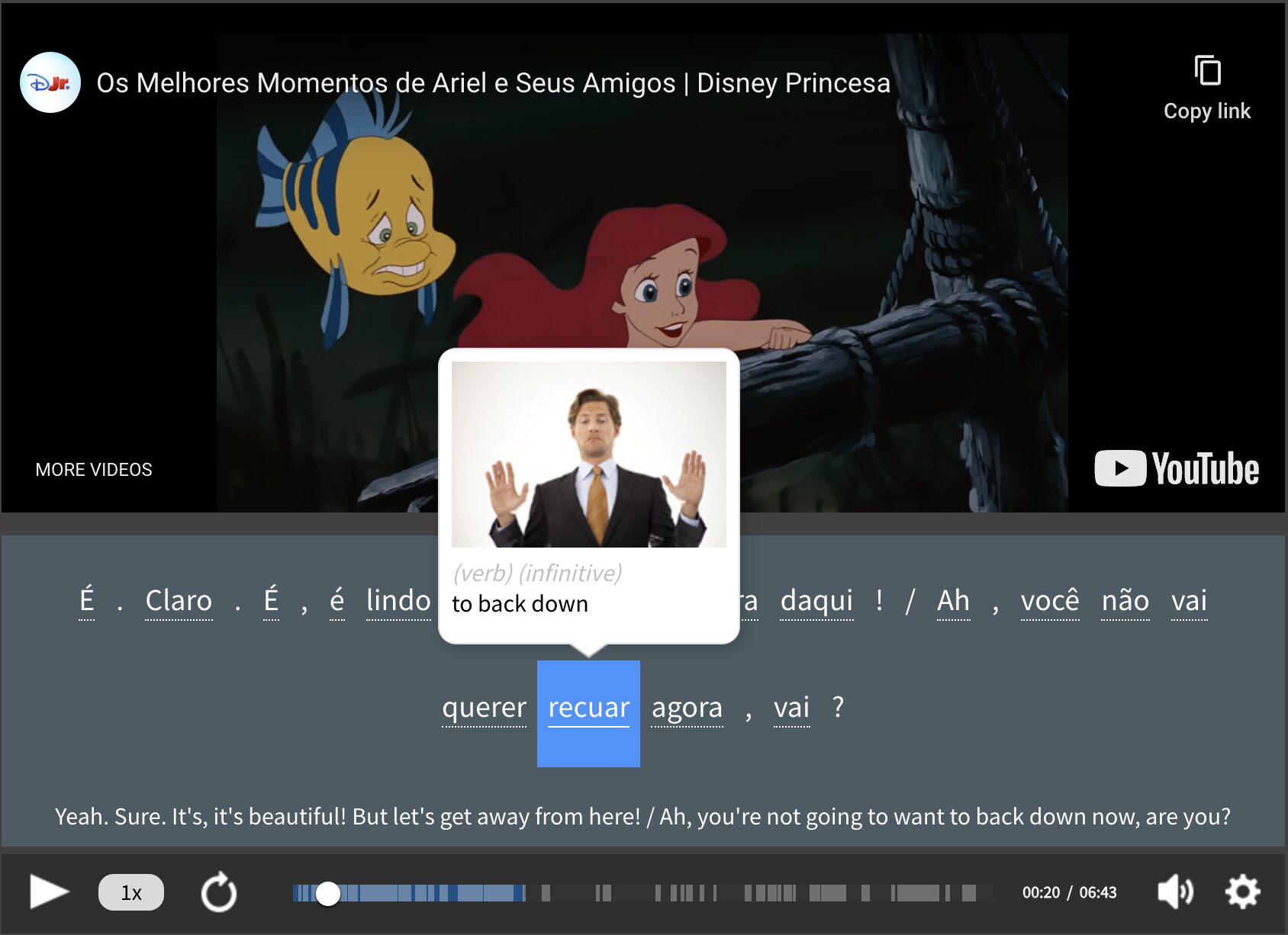

If you're like me and enjoy learning Portuguese through movies and other media, you should check out FluentU. With FluentU, you can turn any subtitled content on YouTube or Netflix into an engaging language lesson.

I also love that FluentU has a huge library of videos picked specifically for Portuguese learners. No more searching for good content—it's all in one place!

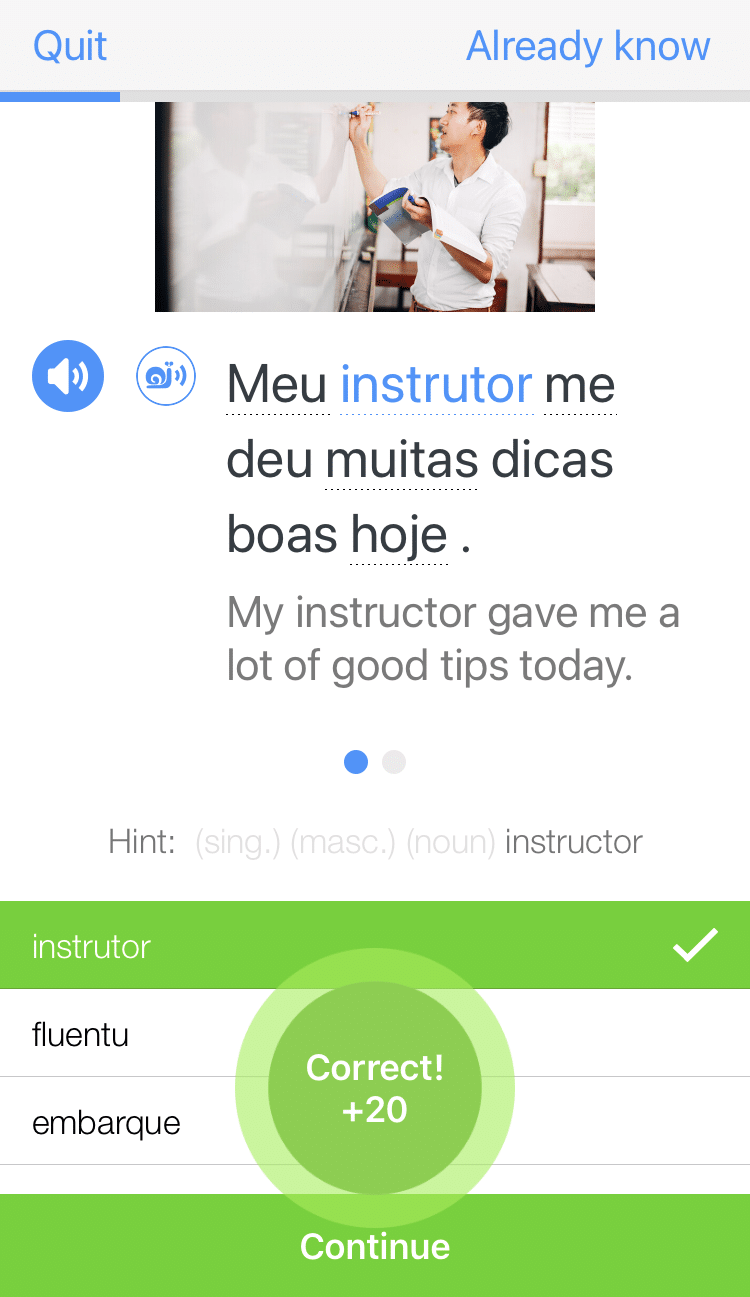

One of my favorite features is the interactive captions. You can tap on any word to see an image, definition, and examples, which makes it so much easier to understand and remember.

And if you're worried about forgetting new words, FluentU has you covered. You'll complete fun exercises to reinforce vocabulary and be reminded when it’s time to review, so you actually retain what you’ve learned.

You can use FluentU on your computer or tablet, or download the app from the App Store or Google Play. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)