Apocopation in Spanish: 15 Shortened Words You Should Know

Apocopation is when words have their endings cut off so that they’re shorter and quicker to say. In both Spanish and English, many of the words you use in your everyday conversations are apocopated.

So let’s put some words on the chopping block and explore apocopation in Spanish. In this post, we’ll talk about how apocopation works and show off 15 common examples of Spanish apocopation.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What is Apocopation?

Apocopation is the shortening of a word. More specifically, the word loses its final letter or letters in order to give us a shorter version of itself with either the same meaning or a very similar one.

This can happen when someone is using slang or informal speech, like the Spanish boli — short for bolígrafo (pen), but also for grammatical reasons.

Almost every language has some form of apocopation, with English having hundreds of shortened words people use every single day. For example, we say “abs” instead of abdominal muscles and “bras” instead of brassieres. Apocopation is used a lot in English, and often the shorter word even becomes the most correct term to use in most cases.

Compared to English, Spanish doesn’t have nearly so many shortened words to remember, but the rules around them work a bit differently. Unlike with English, here are two different types of word shortenings found in Spanish: colloquial shortenings and grammatical ones.

While Spanish certainly shortens words colloquially (like el zoo in place of el zoológico), there are certain words in Spanish that have to be shortened in certain grammatical situations.

Some words lose their final -o because they are followed by a masculine noun, like when primero (first) becomes primer. Other words are shortened depending on their function in a sentence or the word that follows them.

The list of words below are all apocopated for grammatical reasons. When an apocopation is grammatical, its use is required and not optional.

Common Examples of Apocopation in Spanish

1. Uno / Un

Most of you probably know the word uno (one) from learning the numbers in Spanish.

You probably also know un from learning the Spanish articles.

But has anyone ever told you that un is actually the shortening of uno?

Use uno: You use the full form of uno when it is representing either a numeral or a pronoun. For example:

Dile que necesito uno. (Tell him I need one.)

Queremos uno de fresa. (We want a strawberry one.)

Use un: When uno is followed by a masculine singular noun, it gets shortened to un and becomes an article. For example:

Dile que necesito un libro. (Tell him I need a book.)

Queremos un helado de fresa. (We want a strawberry ice-cream.)

2. Primero / Primer

This is another case of a masculine singular noun stealing an -o from a word. How greedy!

Use primero: When you learn the ordinal numbers in Spanish, you normally memorize their masculine singular form. This is one of the instances when you use the whole form, as shown here:

Primero, segundo, tercero, cuarto… (First, second, third, fourth…)

Also use the whole form when it is preceded by el but not followed by a noun:

Juan no fue el último en llegar, fue el primero. (Juan arrived first.) *Note that in Latin American Spanish this sounds odd, while in Castilian Spanish it is commonly used.

Finally, we use the full form primero when it is a time adverb (with the meaning of “first,” “firstly,” “at first”):

Primero corta la cebolla y luego pela las patatas. (First cut the onions and then peel the potatoes.)

Use primer: When it comes to primer, use it only when it is followed by a masculine singular noun. For example:

Este es el primer libro que he comprado en mi vida. (This is the first book I have bought in my life.)

3. Tercero / Tercer

Tercero and tercer are very similar to primero and primer and follow the same sort of rules.

Use tercero: The full word is used when you are listing numerals: primero, segundo, tercero…

You also use the full form when it is preceded by el and not followed by a noun:

Juan llegó el tercero. (Juan finished third.)

And finally, you use tercero when you indicate the third step in a series:

Tercero, añade agua fría. (Third, add some cold water.)

Use tercer: Tercer behaves like primer. So it can only be used when followed by a masculine singular noun:

Vivimos en el tercer piso. (We live on the third floor.)

4. Ciento / Cien

You may be familiar with these words already if you’ve studied some Spanish. And it’s probably not surprising to learn that the number cien (one hundred [100]) is an apocopation of ciento.

The number 100 in Spanish is a very special one and there are some specific situations where you use the full form and when you shorten it.

Use cien: Always shorten ciento to cien when it is followed by a noun, either masculine or feminine. For example:

cien libros (one hundred books)

cien camisas (one hundred shirts)

cien amigos (one hundred friends)

Cien is also used to indicate the number 100 exactly:

…noventa y nueve, cien… (…ninety-nine, one hundred…)

You also use the shortened form in front of the words mil (one thousand), millón (a million), billón (trillion—Yes! This is a huge false friend!), etc.

It also appears in the expression cien por cien (completely, totally)

For example:

Es cien por cien español. (He is totally Spanish.)

Use ciento: Ciento is used for numbers other than mil, millón, billón, etc.:

ciento uno (one hundred and one)

Finally, use ciento for percentages:

veinte por ciento (twenty percent)

5. Bueno / Buen

Bueno and buen are both adjectives and they both mean “good.”

Use bueno: Bueno can either follow a noun or appear by itself. For example:

Es un padre bueno. (He is a good father.)

Es bueno. (He is good, a good person.)

Use buen: Buen, on the other hand, always precedes the noun and cannot appear by itself in the sentence. For example:

Es un buen padre. (He is a good father.)

6. Malo / Mal

The pair malo / mal (bad) works exactly like the pair bueno / buen.

Use malo: If it follows a noun or appears by itself, use malo. For example:

Es un padre malo. (He is a bad father.)

Es malo. (He is bad, a bad person.)

Use mal: If it precedes the noun, use mal. For example:

Es un mal padre. (He is a bad father.)

7. Grande / Gran

This pair appears to behave like the two previous ones, but we have a slight change in meaning this time.

You would use grande only after the noun or by itself and gran only before the noun. However, you also have to think about the meaning of your sentence and decide which one to use.

Use grande: If you use grande (big), you are talking about size. For example:

Es un hombre grande. (He is a big man.)

Use gran: If you use gran (great), you are giving your subjective opinion about how great/impressive/magnificent a person or thing is. For example:

Es un gran hombre. (He is a great man.)

8. Alguno / Algún

The difference between alguno and algún (any) is very easy to learn.

Use alguno: Alguno is a pronoun. This means it substitutes the noun and appears by itself in the sentence. For example:

Dame alguno. (Give me any [one].)

Use algún: On the other hand, algún is a determiner, which means it always has a noun following it. For example:

Dame algún libro. (Give me any book.)

9. Ninguno / Ningún

Ninguno and ningún (not any) are the mirror negative images of alguno and algún.

They behave in the same exact way, and the only difference from the previous pair of words is in their meaning and in the fact that ninguno and ningún only appear in negative sentences.

Use ninguno: Ninguno is a pronoun so it is always by itself. For example:

No me des ninguno. (Don’t give me any [one].)

Use ningún: Ningún needs a noun following it. For example:

No me des ningún libro. (Don’t give me any book.)

10. Santo / San

Santo and san (both meaning “saint”) are a very interesting pair of words.

Use santo: We use santo when we are talking generally about saints but not naming them. For example:

Este libro contiene la vida de muchos santos. (This book contains the lives of a lot of saints.)

It’s also used in expressions like:

ser un santo (to be a saint)

a santo de qué (why on earth)

se le fue el santo al cielo (he/she completely forgot [lit. “the saint went to heaven”]).

You also use santo as a part of a saint’s title, but only when it precedes the name of a saint that starts with To– or Do– :

Santo Tomás (Saint Thomas)

Santo Domingo (Saint Dominic)

Note that the feminine form santa is used as the noun when referring generally to female saints and also precedes the names of all female saints, regardless of how they’re spelled.

Also, be aware that santo/santa are also used as adjectives that mean “holy” or “saintly”.

Use san: You use San as the title for the rest of the names of male saints:

San Miguel (Saint Michael)

San Pablo (Saint Paul)

San Francisco (Saint Francis)

11. Cualquiera / Cualquier

Here we have another couple of words that change depending on their function and their position in the sentence.

Use cualquiera: We use cualquiera (anyone, any, any one) when it is a pronoun or it follows the noun. For example:

Cualquiera puede hacerlo. (Anyone can do it.)

Dame un libro cualquiera. (Give me any book.)

Use cualquier: We use the short form cualquier (any) when it precedes the noun (either masculine or feminine). For example:

Dame cualquier libro. (Give me any book.)

Cualquier taza me vale. (Any mug will do.)

12. Cuánto / Cuán

Cuánto and cuán (how much, a lot, so much) are normally used only in questions and exclamations.

Use cuánto: Cuánto is used when it is followed by a noun or a verb, as shown here:

¡Cuánto has crecido! (You have grown up a lot!)

¿Cuánto es? (How much is it?)

¡Cuánto dinero! (What a large amount of money!)

Use cuán: Cuán (so) can be followed by adjectives and adverbs except for más (more), peor (worse), mayor (older, bigger) and mejor (better). For example:

¡Cuán contento estoy! (I am so happy!)

¡Cuán rápido corres! (You run so fast!)

However, cuán is excessively formal and it is only used in theater plays, poetry and literature in general. During our everyday conversations, we substitute it for qué:

¡Qué contento estoy! (I am so happy!)

¡Qué rápido corres! (You run so fast!)

13. Tanto / Tan

Tanto and tan (so, so much, so many, as much as) transform depending on the word they are modifying.

Use tanto: If it modifies a noun or a verb, use the full form. For example:

Tiene tanto dinero que puede comprar una isla. (He has so much money he can buy an island.)

María come tanto como yo. (María eats as much as I do.)

Use tan: If it modifies an adjective or an adverb, except for más, menos, mejor and peor, use the shortened form:

Eres tan alta como Pedro. (You are as tall as Pedro.)

¿Cómo puedes correr tan rápido? (How can you run so fast?)

14. Mucho / Muy

I bet you didn’t know muy (very) is the apocopation of mucho (a lot)! This pair of words changes its form depending on its meaning and the word it modifies.

Use mucho: Use mucho with nouns and verbs. For example:

Tengo mucho dinero. (I have a lot of money.)

Siempre come mucho. (He always eats a lot.)

Use muy: Use muy with adjectives and adverbs. For example:

Es un parque muy grande. (It is a very big park.)

Mi hermano escribe muy rápido. (My brother can write very fast.)

15. Reciente / Recién

The last pair of words is a little bit tricky.

On the one hand, reciente is an adjective and it means “fresh, recent.” On the other hand, recién is an adverb and it means “freshly, newly.”

Use reciente: We use reciente to modify a noun (normally after it!). For example:

Es un hecho reciente. (It’s a recent development.)

La crisis económica reciente está fuera de control. (The recent economic crisis is out of control.)

Use recién: When it comes to recién, in Spain we normally use it before a past participle. For example:

Recién pintado. (Freshly painted.)

Recién casados. (Newlyweds.)

In Latin America, however, it is very common to see it with other verb forms, with the general meaning of “just, not long ago”:

Recién llegó. (He has just arrived.)

Recién desayuné. (I have just eaten breakfast.)

Spanish is less flexible than English in the use of apocopation. You have to bear in mind some rules and exceptions if you want to get it right every time!

The best way to learn these rules is by hearing the words repeatedly used in context.

If you can’t have regular conversations with native speakers, the next best thing is to listen to these words used in video content like that on FluentU, a program that teaches Spanish using web videos.

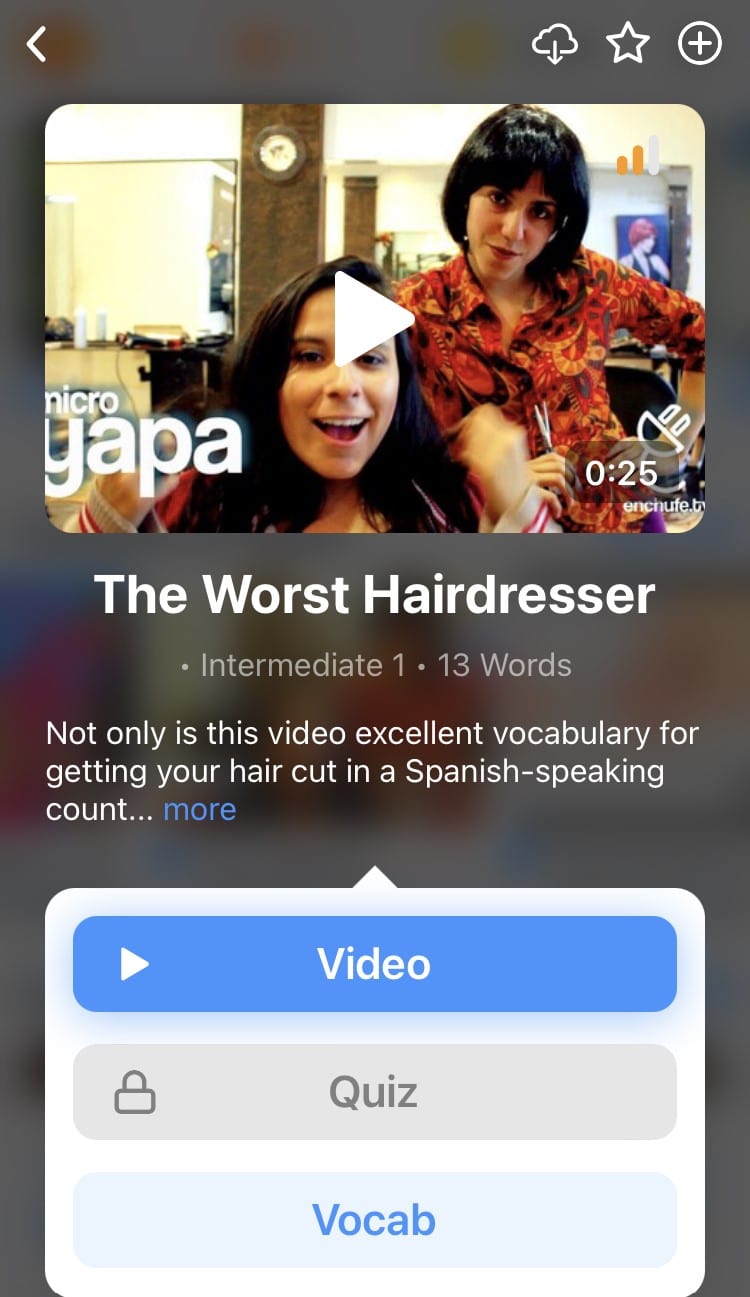

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month)

Follow those rules and you will add these 15 pairs of words into your everyday conversations in the blink of an eye.

Stay curious and, as always, happy learning!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing…

If you've made it this far that means you probably enjoy learning Spanish with engaging material and will then love FluentU.

Other sites use scripted content. FluentU uses a natural approach that helps you ease into the Spanish language and culture over time. You’ll learn Spanish as it’s actually spoken by real people.

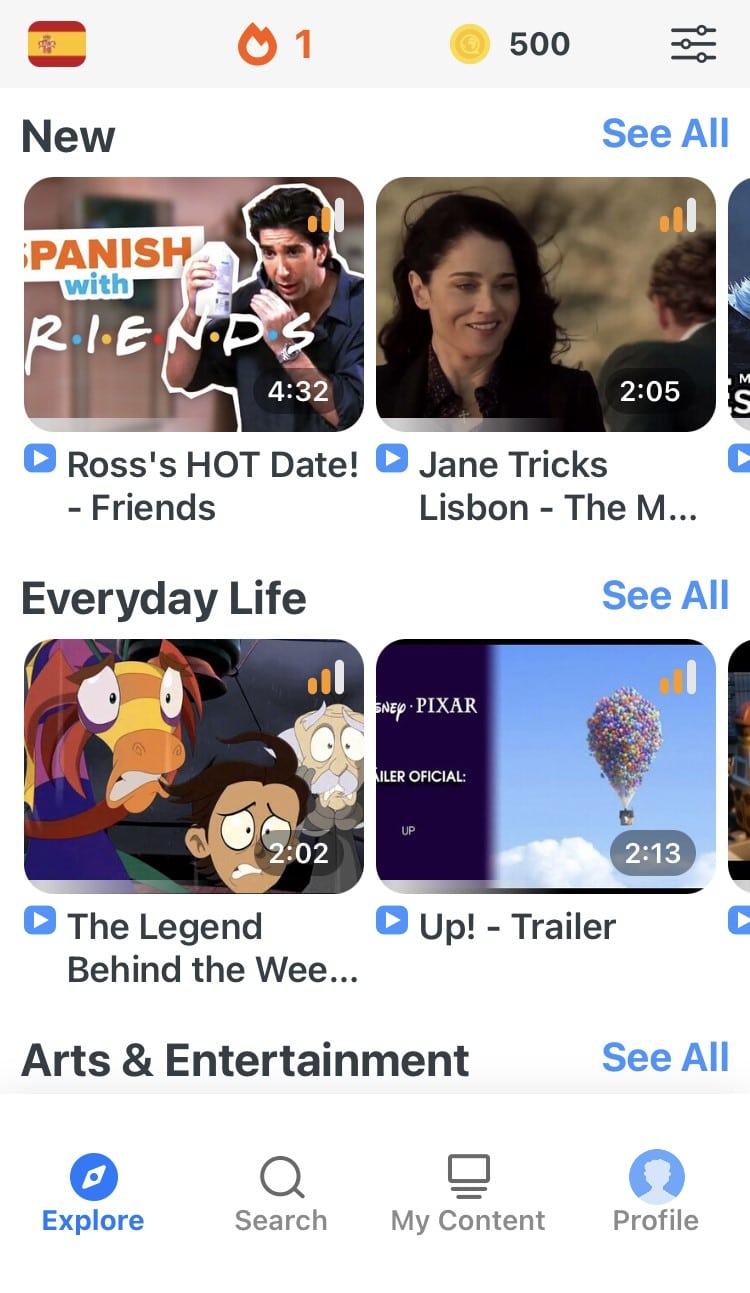

FluentU has a wide variety of videos, as you can see here:

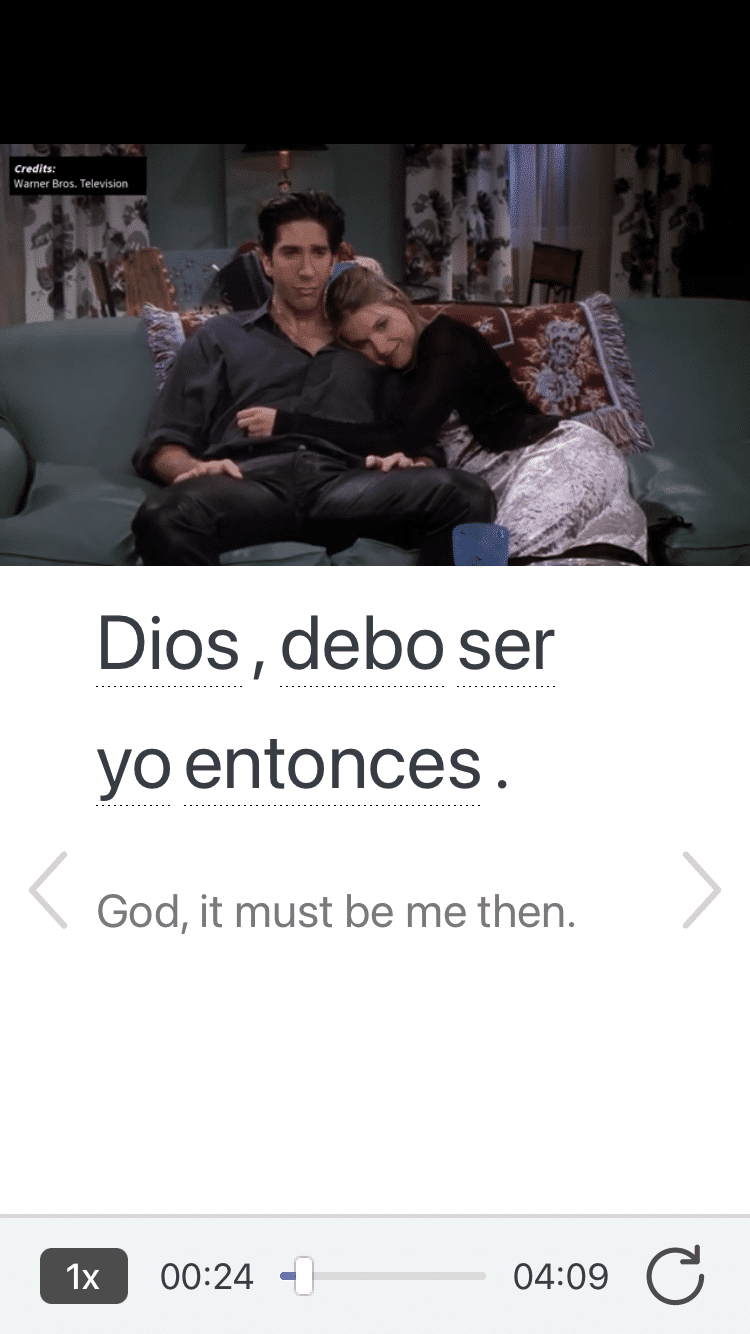

FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive transcripts. You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don’t know, you can add it to a vocab list.

Review a complete interactive transcript under the Dialogue tab, and find words and phrases listed under Vocab.

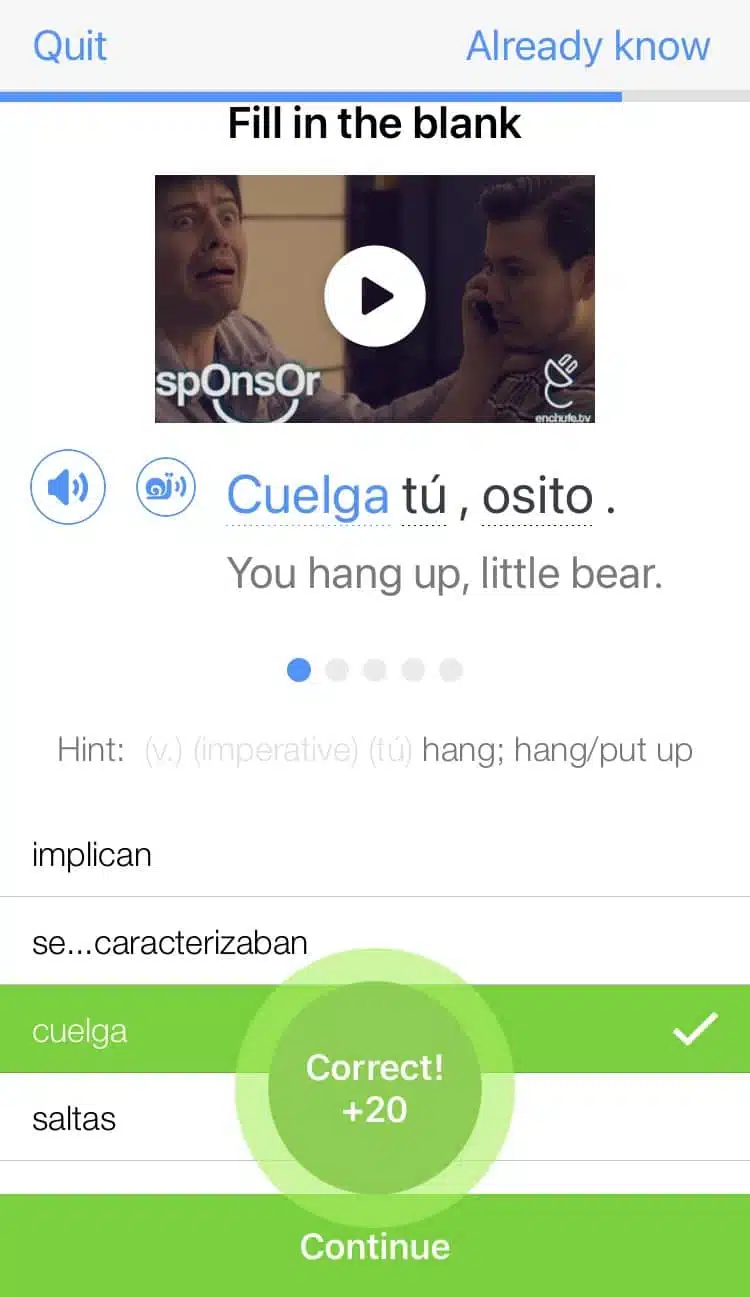

Learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU’s robust learning engine. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you’re on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you’re learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. Every learner has a truly personalized experience, even if they’re learning with the same video.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)