Contents

- 1. Using ser when talking about age

- 2. Mixing up ser and estar

- 3. Not changing the ending on adjectives

- 4. Putting indefinite articles before occupations

- 5. Misplacing adjectives

- 6. Avoiding double negatives

- 7. Using the plural form with la gente (people)

- 8. Overusing capitalization

- 9. Saying “Gracias para…”

- 10. Confusing muy and mucho

- 11. Falling for false friends

- 12. Using the wrong prepositions

- 13. Adding prepositions where they’re not needed

- 14. Forgetting the personal a

- 15. Ordering food using “Puedo tener…?”

- 16. Mixing up words that sound similar

- 17. Saying “Hice un error”

- 18. Using gustar incorrectly

- 19. Responding to gustar incorrectly

- 20. Forgetting accents

- 21. Pronouncing the h sound

- 22. Forgetting to use the subjunctive

- And One More Thing…

22 Common Spanish Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

We all make mistakes when learning a new language. Chances are you’ve made some of the ones on this list. But instead of letting a few mistakes ruin your confidence, you can use them as a learning opportunity.

By learning 22 of the most common Spanish mistakes and how to avoid them, you can speak with more confidence, ease and accuracy.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

1. Using ser when talking about age

In English we use the verb “to be” when talking about age: “I’m 25 years old.” But in Spanish, the verb tener (to have) is used with age.

To say that you’re 25 years old, you’d say “Tengo 25 años” (I’m 25). This translates literally to “I have 25 years,” hence the common mistake.

There are quite a few other Spanish phrases that use the verb tener while their English counterparts use “to be.” Here are some common ones:

| Spanish phrase | English translation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| tener calor | to be hot | ¿Puedes subir el aire? ¡Tengo calor! (Can you turn up the air? I'm hot!) |

| tener frío | to be cold | Puedo cerrar la ventana si tienes frío. (I can close the window if you're cold.) |

| tener hambre | to be hungry | Desayuné mucho así que no tengo mucha hambre. (I had a big breakfast so I'm not very hungry.) |

| tener sed | to be thirsty | Después de correr, siempre tengo mucha sed. (After running, I'm always really thirsty.) |

| tener sueño | to be sleepy | No puedo concentrarme en mi tarea cuando tengo sueño. (I can't focus on my homework when I'm sleepy.) |

| tener cuidado | to be careful | Cuando camines por la calle, debes tener cuidado con los carros. (When you walk on the street, you should be careful with the cars.) |

| tener miedo | to be afraid | Tengo miedo de los perros. (I'm afraid of dogs.) |

| tener prisa | to be in a hurry | Vamos a llegar tarde a la cita, así que tenemos prisa. (We're going to be late for the appointment, so we're in a hurry.) |

| tener razón | to be right | En esta discusión, creo que tienes razón. (In this argument, I think you're right.) |

| tener suerte | to be lucky | Tenemos suerte de vivir cerca de la playa. (We're lucky to live near the beach.) |

2. Mixing up ser and estar

This is a very important one because it can really change the meaning of what you say. For example, the Spanish adjective aburrido can mean “bored” or “boring” depending on the context.

If you say “Soy aburrido,” it means that you’re a boring person in general. But if you say “Estoy aburrido,” it means that you feel bored at the moment

Remember that ser and estar both mean “to be,” but ser is generally used for more permanent things while estar is for temporary states or conditions.

The confusing exception is when talking about the location of a certain place (estar) or where an event takes place (ser). In these cases, it’s the opposite of what you might think:

¿Dónde está el hospital?

(Where’s the hospital?)

El concierto es en el estadio.

(The concert is at the stadium.)

3. Not changing the ending on adjectives

Another common mistake is forgetting to change the ending of an adjective depending on the gender of who/what you’re talking about and if it’s singular or plural.

To say that a male is bored, you’d use aburrido. When talking about a female, you’d use aburrida. For more than one female, you’d use aburridas and for more than one male or a mixed-gender group, you’d use aburridos.

This is also true for many professions, such as abogado (male lawyer) and abogada (female lawyer) or professor (male teacher) and profesora (female teacher).

4. Putting indefinite articles before occupations

If you try to translate directly from English to Spanish, “I’m a teacher” would be “Soy un professor.” But this is incorrect and shows why direct translation is not always a good idea.

When stating occupations in Spanish, don’t use the indefinite article (un/una). Rather, just use the verb ser (to be) plus the occupation. For example:

Soy profesora.

(I’m a teacher.)

Eres artista.

(You’re an artist.)

Él es ingeniero.

(He’s an engineer.)

5. Misplacing adjectives

In English, our adjectives come before the noun: a big house, a blue shirt, a beautiful smile. In Spanish, however, adjectives usually come after the noun: una casa grande, una camiseta azul, una sonrisa bonita.

Be aware that there are certain instances where the adjective does come before the noun in Spanish, and the position can actually change the meaning of the adjective. For example:

Ellos tienen su propia casa.

(They have their own house.)

No es el vestido propio para el evento.

(It’s not the right dress for the event.)

Es la única talla que tenemos.

(It’s the only size we have.)

Valeria es una persona única.

(Valeria is a unique person.)

Es un gran músico.

(He’s a great musician.)

Rusia es un país grande.

(Russia is a big country.)

You can learn more about Spanish adjective placement in this video:

6. Avoiding double negatives

Double negatives in the English language often make us cringe because they’re simply poor grammar. But in Spanish, double negatives thrive!

For example, take the phrase “I didn’t write anything.” In Spanish, you’d say “No escribí nada” (Literally: “I didn’t write nothing”).

As a general rule, Spanish phrases don’t mix positive and negative words. So if you have a “no” before your verb, you’ll only ever see a negative word after the verb. With positive verbs, you’ll use the positive equivalencies:

| Positive words | Negative words |

|---|---|

| alguien — somebody | nadie — nobody |

| algo — something | nada — nothing |

| algún / alguna — some/something | ningún / ninguna — no/none |

| siempre — always | nunca / jamás — never |

| también — also | tampoco — neither |

Take a closer look at these examples to get a better feel for the concept:

No la he visto nunca. (I’ve never seen her.)

No hay nadie aquí. (There’s nobody here.)

Nunca dice nada en clase. (He never says anything in class.)

Ella tampoco hizo nada ayer. (She didn’t do anything yesterday either.)

Personally, this was one of the grammar concepts that tripped me up the most even though it sounds pretty simple. But honestly, I’ve found that just listening to native content often helps this.

Try adding (Spanish) subtitles to the content you listen to in Spanish, or watch dubbed versions of your favorite shows. For example, here’s video lesson using a Spanish-dubbed episode of SpongeBob:

7. Using the plural form with la gente (people)

In English the word “people” is a collective noun that must always be used with verbs in the third person plural: “People are good-hearted.”

In Spanish, however, the word for “people” (la gente) is singular. Yes, it’s a strange concept to get used to at first, but once you get the hang of it the word shouldn’t cause you any more trouble.

Here are a few examples to get you more comfortable with the idea:

La gente de Perú es muy amable. (The people of Peru are very friendly.)

La gente se divierte en el parque. (People have fun in the park.)

La gente mayor disfruta de la música clásica. (Older people enjoy classical music.)

8. Overusing capitalization

Capitalization rules are very different between Spanish and English, with significantly less capitalization on the Spanish side. Words that are capitalized in Spanish include:

• Names of people (Cristiano Ronaldo)

• Names of places (Madrid, España)

• Names of newspapers and magazines (El País)

• The first word of titles of movies, books, articles, plays, etc.

Words that are not capitalized in Spanish:

• Days of the week (lunes, martes, miércoles – Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday)

• Months of the year (enero, febrero, marzo – January, February, March)

• Words in titles, except the first (“Cien años de soledad” — “100 Years of Solitude”)

• Languages (Estudio español. — I study Spanish.)

• Religions (Mis padres son católicos. — My parents are Catholic.)

• Nationality (Soy estadounidense. — I’m American.)

9. Saying “Gracias para…”

Mixing up por and para is a very common mistake for Spanish learners, as they both can mean “for.” In fact, they’re so commonly confused that we created a whole post about it.

One situation where they’re often mixed up is when saying thank you. To thank someone for doing something for you or giving you something, we use por, not para. For example:

¡Gracias por invitarme a tu fiesta! (Thanks for inviting me to your party!)

Gracias por tu ayuda. (Thanks for your help.)

Gracias por el hermoso regalo. (Thank you for the beautiful gift.)

10. Confusing muy and mucho

It’s very common for Spanish learners to mix up the words muy and mucho. Muy is an adverb that means “very” or “really.” It goes in front of an adjective or adverb and never changes. For example:

Hablas español muy bien.

(You speak Spanish very well.)

Estoy muy cansada.

(I’m really tired).

Camina muy rápido.

(He walks really fast.)

Mucho can be used as an adjective that means “a lot,” “many” or “much.” In this case, it goes before a noun and changes form (mucho, muchos, mucha or muchas) depending on the gender and number of that noun:

Tengo mucha hambre.

(I’m really hungry.)

Tomé mucho vino.

(I drank a lot of wine.)

¡Muchas gracias por la cena!

(Thank you so much for dinner!)

It can also be used as an adverb to modify verbs, in this case translating to “a lot” and going after the verb (without changing form). For example:

Ella trabaja mucho. (She works a lot.)

Here’s a quick review of the difference between muy and mucho:

11. Falling for false friends

There are a lot of “false friends” between Spanish and English. These are words that sound the same but have different meanings. Here are a few that often cause (quite embarrassing) mistakes:

- Embarazada means “pregnant.” “Embarrased” in Spanish is avergonzado or tener verguenza (to be embarrassed).

- Excitado means “excited,” but in a sexual way. To say that you’re excited in a non-sexual way, use emocionado instead (or emocionada if you’re female).

- Preservativo sounds a lot like “preservative,” but it actually means “condom.” If you want to know if a certain food or beauty product contains preservatives, use conservante to avoid an awkward moment.

- Dato might look like the word “date,” but it actually means “fact.” If someone asks you for tus datos, they’re asking for your personal information. If you want to ask someone out on a date, use cita instead.

12. Using the wrong prepositions

As we’ve already seen with por and para, Spanish prepositions are tricky. They often don’t translate directly between English and Spanish, so we have to memorize which prepositions go with which verbs.

Here are a few verb/preposition pairs that create a lot of mistakes among Spanish learners:

- Soñar con: In Spanish, we say soñar con to mean “to dream of/about.” For example: Anoche soñé con mi exnovio (I dreamt about my ex-boyfriend last night).

- Pensar en/de: We use pensar en to say that we’re thinking about someone or something. For example: Siempre pienso en ti (I always think about you). To talk about an opinion, we can use pensar de: ¿Que piensas de este vestido? (What do you think of this dress?)

- Casarse con: When talking about marriage, we use the Spanish preposition con. For example: Me caso con mi mejor amigo (I’m marrying my best friend) or Estoy casada con mi mejor amigo (I’m married to my best friend).

13. Adding prepositions where they’re not needed

In addition to using the wrong prepositions, Spanish learners often add prepositions where there shouldn’t be any. Here are a few of the most common examples:

- Buscar: This verb means “to look for,” with the preposition included in the meaning. So you should never say “buscar por” or “buscar para” when talking about looking for something or someone. For example: Estoy buscando mis llaves (I’m looking for my keys). The same goes for esperar (to wait for).

- Pedir: This is another verb that has the “for” included in the meaning. So we can say “Ella le pidió ayuda a su vecina” (She asked her neighbor for help) and it’s perfectly correct. (Pedir can also mean “to order,” as in “to order a salad.”)

- Intentar: To say “to try” or “to attempt” to do something, we can use intentar (with no preposition) or tratar de. This causes some confusion, as one uses a preposition and the other doesn’t. For example: Intenté abrir la puerta pero estaba cerrada (I tried to open the door but it was locked).

14. Forgetting the personal a

The personal a is a preposition we use in Spanish when a sentence’s direct object is a person. It’s often forgotten by English speakers simply because it doesn’t exist in Spanish, and it doesn’t have a direct translation. For example:

Voy a visitar a mis abuelos. (I’m going to visit my grandparents.)

As you can see, there’s no equivalent word in the English translation. But nevertheless, it’s required in Spanish. Here are a few more examples:

Necesito llamar a mi amigo. (I need to call my friend.)

Los estudiantes respetan a su maestra. (The students respect their teacher.)

Notice that when the direct object is replaced with a direct object pronoun, the personal a disappears:

Los estudiantes la respetan. (The students respect her.)

15. Ordering food using “Puedo tener…?”

There are many ways to order food or drinks in Spanish. But “Puedo tener…?” is not one of them. This is a direct translation of the English phrase “Can I have…?” and it can be heard in many restaurants in touristy areas of the Spanish-speaking world.

Yes, the server will understand what you’re saying. But try using one of these phrases instead if you want to sound less like a tourist and more like a native speaker:

• Me da…

(Can you get me…?)

• Me gustaría…

(I’d like…)

• Para mí…

(I’ll have…)

• ¿Puede traerme…?

(Could you bring me…?)

16. Mixing up words that sound similar

Just like in English, there are many pairs and groups of words in Spanish that sound similar and are therefore often mixed up. These are called homophones, and it helps to know some of the most common:

• Hambre

(hunger), hombre

(man) and hombro

(shoulder)

• Pimienta

(pepper, as in salt and pepper) and pimiento

(pepper, as in the vegetable)

• Cabello

(hair) and caballo

(horse)

• Cansado

(tired) and casado

(married)

• Hola

(hello) and ola

(wave)

17. Saying “Hice un error”

There’s nothing worse than making a mistake when trying to acknowledge a previous mistake! In Spanish, we don’t use hacer (to do/make) to say that we’ve made a mistake.

Instead, we use the verb cometir (to commit). Here are some examples:

Cometí un error. ¡Por favor, perdóname! (I made a mistake. Please forgive me!)

Por favor corrígeme cuando cometa un error. Quiero mejorar mi español. (Please correct me when I make a mistake. I want to improve my Spanish.)

Cometer errores es una parte natural del aprendizaje de un nuevo idioma. (Making mistakes is a natural part of learning a new language.)

18. Using gustar incorrectly

Gustar is a confusing verb because it functions differently than its English meaning. When you say “Me gusta leer,” it literally means that reading is pleasing to you.

Because the verb gustar is actually talking about the thing or the activity, not the person who likes the thing or the activity, you must change its form depending on the gender and number of the noun that comes after it. For example:

Me gustan las galletas. (I like cookies.)

Les gusta la playa. (They like the beach.)

Me gustas. (I like you. — with a romantic connotation)

There are many other verbs like this in Spanish such as encantar (to delight) and preocupar (to worry)—check out this list of 100 of them here.

If you’re still confused about how to use gustar, you can listen to this silly song that packs a whole lesson into less than two minutes:

19. Responding to gustar incorrectly

Another common mistake involving the verb gustar is saying, for example, “Yo me gusta…” when it should be “A mí me gusta…”. This is only necessary when you want to emphasize what you like in contrast to someone else. For example:

No me gustan las peliculas de terror.

(I don’t like horror movies.)

A mí me gustan mucho.

(I like them a lot.)

Similarly, we can’t respond with “Yo también” (Me too) or “Yo tampoco” (Me neither) when someone tells us what they like. Instead, we must say “A mí tambien” or “A mí tampoco.”

20. Forgetting accents

Accents in Spanish are important because they can tell you how a word should be pronounced. They can also change the meaning of a word completely. For example:

• el

(the) vs. él

(he)

• si

(if) vs. sí

(yes)

• porque

(because) vs. por qué

(why)

• como

(I eat) vs. cómo

(how)

• papa

(potato) vs. papá

(dad)

Don’t get caught saying something like “My potato is a lawyer.” Remember to use your accents when they’re needed!

21. Pronouncing the h sound

Of course, there are many pronunciation mistakes that happen when you’re learning a new language. But one of the most common in Spanish is with words with h, especially when the h is in the middle of the word.

This is because in Spanish, the h is silent. Listen to how it’s pronounced—or, more accurately, not pronounced—in these words:

• hambre

(hunger)

• hola

(hello)

• zanahoria

(carrot)

• vehículo

(vehicle)

• ahorros

(savings)

Pay attention whenever you’re pronouncing a Spanish word with an h and you’ll sound much more like a native speaker!

22. Forgetting to use the subjunctive

This last one is for more advanced Spanish learners. Even if your Spanish is really good, forgetting to use the subjunctive mood can be an obvious clue that you’re not a native speaker.

The subjunctive is used to express doubt, uncertainty, desire, emotions and various hypothetical or non-factual situations. Here are some examples:

Ojalá sepa la respuesta. (I hope he knows the answer.)

Es bueno que tu familia se lleve tan bien. (It’s nice that your family gets along so well.)

No creo que el banco esté abierto hoy. (I don’t think the bank is open today.)

Estoy buscando un profesor que hable español con fluidez. (I’m looking for a teacher who’s fluent in Spanish.)

Espero que hayas disfrutado la comida. (I hope you’ve enjoyed the food.)

To avoid the common mistake of using the indicative when the subjunctive is needed, try to learn the triggers for using the subjunctive. You can also practice and familiarize yourself with common subjunctive phrases.

By learning to avoid these common mistakes, you’ll boost yourself up to a whole new level of Spanish.

You’ll be even less likely to make common mistakes if you use an immersive program to learn the language, like FluentU. This and other immersion programs let you hear Spanish as it’s actually used by native speakers, allowing you to learn naturally and in context.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing…

If you’re like me and prefer learning Spanish on your own time, from the comfort of your smart device, I’ve got something you’ll love.

With FluentU’s Chrome Extension, you can turn any YouTube or Netflix video with subtitles into an interactive language lesson. That means you can learn from real-world content, just as native speakers actually use it.

You can even import your favorite YouTube videos into your FluentU account. If you’re not sure where to start, check out our curated library of videos that are handpicked for beginners and intermediate learners, as you can see here:

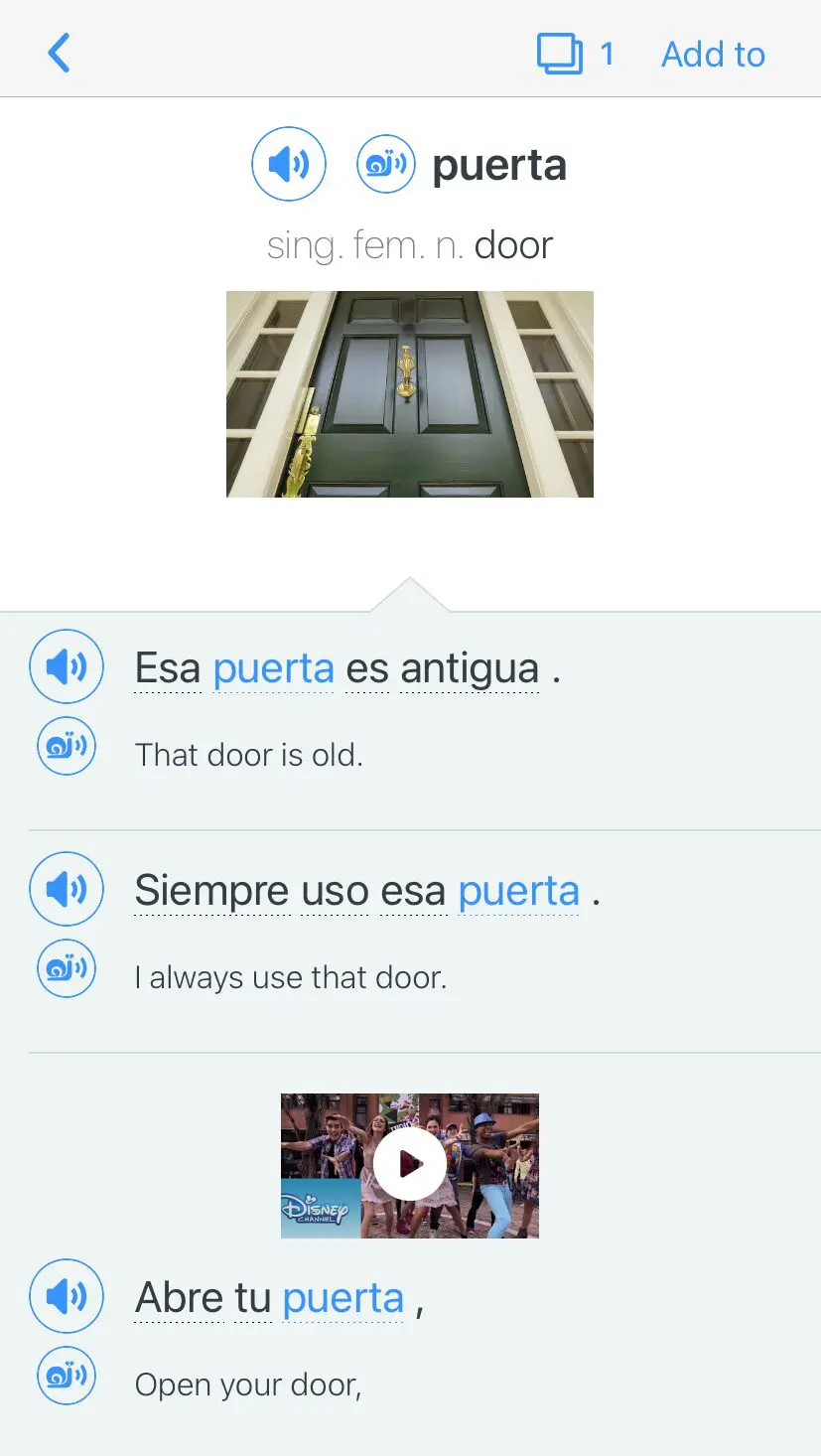

FluentU brings native Spanish videos within reach. With interactive captions, you can tap on any word to see an image, definition, pronunciation, and useful examples.

You can even see other videos where the word is used in a different context. For example, if I tap on the word "puerta," this is what pops up:

Want to make sure you really remember what you've learned? We’ve got you covered. Practice and reinforce the vocab from each video with learn mode. Swipe to see more examples of the word you’re learning, and play mini-games with our dynamic flashcards.

The best part? FluentU tracks everything you’re learning and uses that to create a personalized experience just for you. You’ll get extra practice with tricky words and even be reminded when it’s time to review—so nothing slips through the cracks.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download our app from the App Store or Google Play.

Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)