Contents

Spanish Sentence Structure and Word Order [With Examples]

Spanish sentence structure is one of those essential things to know in order to communicate effectively. If you accidentally switch the order of the words, you can end up saying something completely different from what you mean.

While misunderstandings can make for some humorous moments, we don’t want you in that position. So here’s everything you need to know about constructing sentences in Spanish, so you can speak and write freely without getting tripped up on word order.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

The Basics of Spanish Sentence Structure

Sentence structure involves the word order in a sentence. It’s how you put all the parts together to form grammatically correct sentences.

The typical word order in Spanish is SVO (Subject, Verb, Object). This is the same as in English, but there can be big differences between the two languages, and we don’t always use this formula.

Spanish is a very flexible language, and most of the time you’ll be able to change that order without altering the meaning of the sentence. However, there are times when changing the word order will lead to misunderstandings or grammatical errors.

That’s why it’s important to learn the rules and exceptions of Spanish sentence structure.

Word Order in Different Types of Sentences

In the following points, we’ll go over word order in all the main types of sentences and questions. You’ll also learn where to insert Spanish adjectives and adverbs in the sentence, and how the meaning can be different if you make some little changes.

Spanish Declarative Sentences

Declarative sentences are pretty straightforward because they tend to look the same both in Spanish and in English.

In order for a sentence to be grammatical, we need at least a subject and a verb. Then we can add an object or any other word category we may need. For example:

Yo leo. (I read.)

Yo leo libros. (I read books.)

There are, however, a few situations when a declarative sentence in Spanish can be a little different from its English translation.

| Rules and Exceptions | Examples |

|---|---|

| In Spanish you don't need to add a subject, except if used for emphasis. | Leo libros.

(I read books.) Yo leo libros. (I read books. As in, it is me who reads books, not you, not him.) |

| So you'll always have a conjugated verb which agrees in person and number with the omitted subject. | (Yo) Compro manzanas.

(I buy apples.) (Tú) Compras manzanas. (You buy apples.) (Ellos) Compran manzanas. (They buy apples.) |

| Insert pronouns directly before the conjugated verb, not after it. | Las compro.

(I buy them.) Lo leo. (I read it.) Se la enviamos. (We send it to her.) |

| Sometimes you can put the verb in front of the subject, especially when dealing with passives. | Se venden libros.

(Books for sale.) Se habla español aquí. (Spanish is spoken here.) |

| You can often change the word order with just a slight change in the meaning. | (Yo) leo libros.

(I read books.) Libros leo (yo). (Literally: "Books I read." Meaning: It is books that I read, not magazines.) Leo libros (yo). (I read books. Meaning: I read books, I don't sell them, I don't burn them, I just read them.) |

Use that last technique only when you want to put emphasis on a specific sentence constituent. However, bear in mind that you won’t be able to do this every time (like with adjective placement, as we’ll see in a bit).

Try to follow the basic scheme and the rules above so that you always have it right.

Negation in Spanish

Spanish negation is really easy. Basically, you just have to add “no” before the verb.

Here are a few different ways to make negative sentences in Spanish.

| Spanish Negation Rules | Examples |

|---|---|

| If the sentence only consists of a verb and an object, just add no before the verb. | No compro manzanas.

(I don't buy apples.) No leo libros. (I don't read books.) |

| If you have a personal pronoun in the sentence, the no goes right after it. | Él no vino. (He didn't come.) |

| But if you have a direct/indirect object pronoun in the sentence, the no goes before it. | No las compro.

(I don't buy them.) No los leo. (I don't read them.) |

| This is also true when you have two pronouns. | No se los leo. (I don't read them to him.) |

| If the answer to a question is negative, you'll probably need two negative words (and the verb). | ¿Lees libros?

No, no los leo. (Do you read books? No, I don't.) |

| You can also use negative words such as nada (nothing), nadie (nobody) and nunca (never). When used alone, they go before the verb. | Nunca leo.

(I never read.) Nadie ha comprado manzanas. (Nobody has bought apples.) |

| Or, to use double negation, you can put no before the verb, and add the negative word after the verb. | No leo nunca.

(I never read.) No ha comprado nadie manzanas. (Nobody has bought apples.) |

| In Spanish, you can even find three and four negative words in one sentence! | No leo nada nunca.

(I never read anything.) No leo nunca nada tampoco. (I never read anything either.) |

Questions in Spanish

Asking questions in Spanish is easier than in English because you don’t use auxiliary verbs to make the question. The only thing you have to bear in mind is whether you’re asking a yes/no question or are expressing incredulity.

| Forming Questions | Examples |

|---|---|

| To add incredulity, just add question marks at the beginning and end of the declarative sentence. | María lee libros. → ¿María lee libros?

(Maria reads books. → Really? Maria reads books? How surprising!) |

| If you're expecting a real answer, you can invert the subject and verb. | ¿Está tu madre en casa?

(Is your mother home?) |

| But it's also common to just use the declarative sentence plus question marks. | ¿Te gustan las uvas?

(Do you like grapes?) |

| When we have a question word, we normally use inversion. | ¿Por qué lee María?

(Why does María read?) ¿Cuánto cuestan las manzanas? (How much do the apples cost?) |

Indirect Questions in Spanish

An indirect question is a question embedded in another sentence. They normally end up with a period, not a question mark, and they tend to begin with a question word, as in English.

As you can see in the examples below, indirect questions look exactly the same as declarative sentences; there’s no inversion nor any other changes.

| Forming Indirect Questions | Examples |

|---|---|

| The first type of indirect questions contains a question word. | No sé por qué María lee.

(I don't know why Maria reads.) Dime cuánto cuestan las manzanas. (Tell me how much the apples cost.) |

| The second type requires a yes/no answer, and instead of using a question word, you’ll have to use si (if, whether). | Me pregunto si María lee.

(I wonder if Maria reads.) Me gustaría saber si has comprado manzanas. (I would like to know if you have bought apples.) |

| You can also add o no (or not) at the end of the indirect question. | ¿Me podría decir si María lee o no? (Could you tell me whether María reads or not?) |

Spanish Adjective Placement

When you start studying Spanish, one of the first rules you’ll have to learn is that adjectives usually come after the noun in Spanish.

El perro grande (the big dog)

El libro amarillo (the yellow book)

El niño alto (the tall child)

However, this rule is broken quite often as there are some adjectives that can take both positions. Bear in mind, though, that the meaning of the sentence changes depending on the position of those adjectives!

Here you have some of them:

| Adjective | Before the noun | After the noun |

|---|---|---|

| Grande | When used before the noun, it changes to gran, and it means great: un gran libro (a great book). | When used after the noun, it means big: un libro grande (a big book). |

| Antiguo | It means old-fashioned or former: un antiguo alumno (a former student). | It means antique: un libro antiguo (an antique book). |

| Mismo | It means "the same": el mismo libro (the same book). | It means itself, himself, herself, etc.: el niño mismo (the child himself). |

| Nuevo | It means recently made: un nuevo libro (a recently made book). | It means unused: un libro nuevo (an unused book). |

| Propio | It means one's own: mi propio libro (my own book). | It means appropriate: un vestido muy propio (a very appropriate dress). |

| Pobre | It means poor, in the sense of pitiful: el pobre niño (the poor child). | It means poor, without money: el niño pobre (the poor, moneyless child). |

| Solo | It means only one: un solo niño (only one child). | It means lonely: un niño solo (a lonely child). |

| Único | It means the only one: el único niño (the only child). | It means unique: un niño único (a unique child, but ser hijo único means to be an only child). |

Spanish Adverb Placement

Adverb placement is pretty flexible in Spanish, although there’s a tendency to put them right after the verb or right in front of the adjective:

El niño camina lentamente. (The boy walks slowly.)

Este tema es horriblemente difícil. (This topic is horribly difficult.)

You can place adverbs almost anywhere in the sentence, as long as they’re not far from the verb they modify:

Ayer encontré un tesoro. (Yesterday I found some treasure.)

Encontré ayer un tesoro. (I found yesterday some treasure.) *Still correct in Spanish!*

Encontré un tesoro ayer. (I found some treasure yesterday).

If the object is too long, it’s much better to put the adverb directly after the verb and before the object. For example, the following:

Miró amargamente a los vecinos que habían llegado tarde a la reunión. (He looked bitterly at his neighbors who had arrived late to the meeting.)

is much better than:

Miró a los vecinos que habían llegado tarde a la reunión amargamente. (He looked at his neighbors who had arrived late to the meeting bitterly.)

You probably know that you can create an adverb from most Spanish adjectives by adding the ending -mente to the feminine, singular form of the adjective. For example: rápido → rápida → rápidamente (quickly).

When you have two adverbs modifying the same verb, add -mente only to the second one:

El niño estudia rápida y eficientemente. (The boy studies quickly and efficiently.)

Mi hermano habla lenta y claramente. (My brother speaks slowly and clearly.)

Remember that there are some adverbs that don’t end in -mente, like mal (poorly) and bien (well).

You may also want to review Spanish conjunctions and prepositions, which are used in many Spanish sentences.

Exposing Yourself to Spanish Sentence Structure

You can get a better understanding of Spanish sentence structure by seeing it in actual Spanish-language content.

For example, you can read a simple Spanish book and note key sentence structure elements. If it’s your book, you could mark it up, writing the part of speech, form, tense, etc. of each word in the sentence.

You can also use FluentU to hear spoken Spanish in videos.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. If you decide to sign up now, you can take advantage of our current sale!

You can also check out the FluentU Spanish YouTube channel. There are tons of in-depth video lessons using Spanish-dubbed clips of popular movies and TV shows to teach vocabulary, grammar and expressions.

You’ve now taken many steps further into your Spanish learning! By learning proper sentence structure, you’ll improve your Spanish writing, speaking and overall language skills.

Practice will make all these concepts familiar and instinctive over time. Soon enough, you’ll be hopping into conversations with grace and confidence!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing…

If you've made it this far that means you probably enjoy learning Spanish with engaging material and will then love FluentU.

Other sites use scripted content. FluentU uses a natural approach that helps you ease into the Spanish language and culture over time. You’ll learn Spanish as it’s actually spoken by real people.

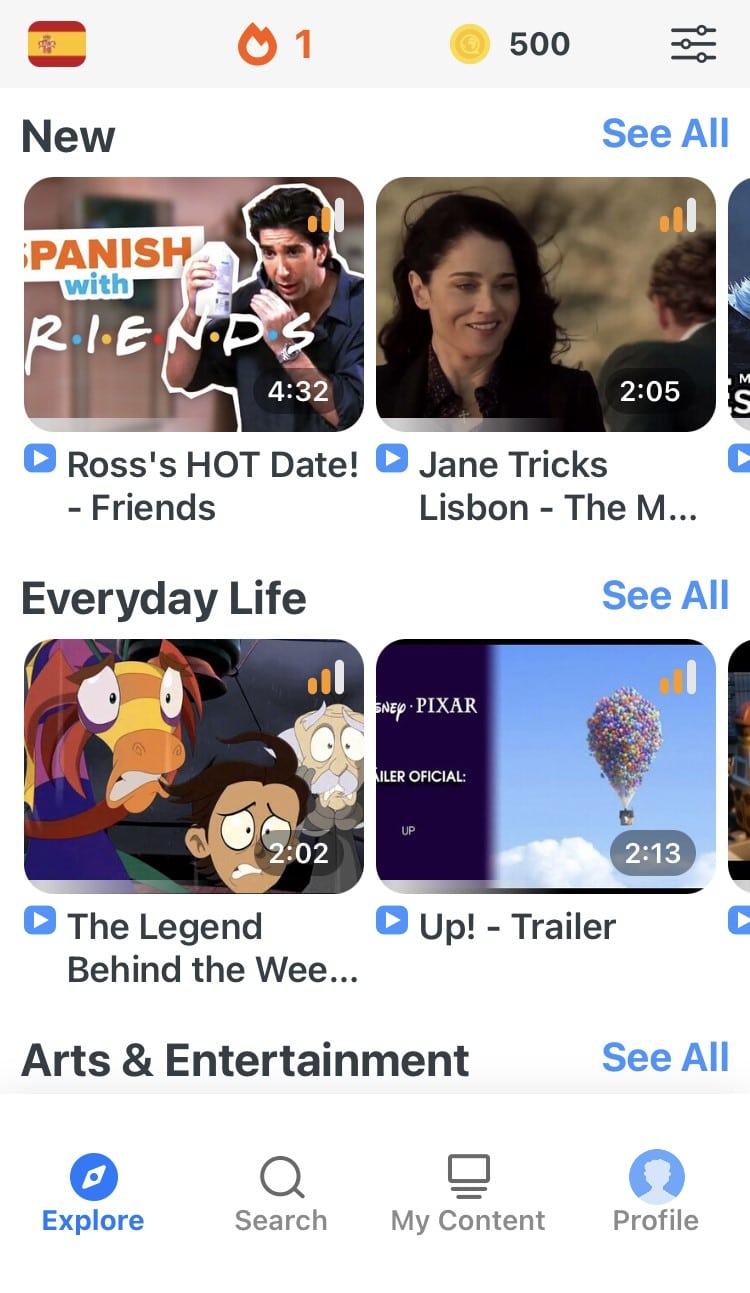

FluentU has a wide variety of videos, as you can see here:

FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive transcripts. You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don’t know, you can add it to a vocab list.

Review a complete interactive transcript under the Dialogue tab, and find words and phrases listed under Vocab.

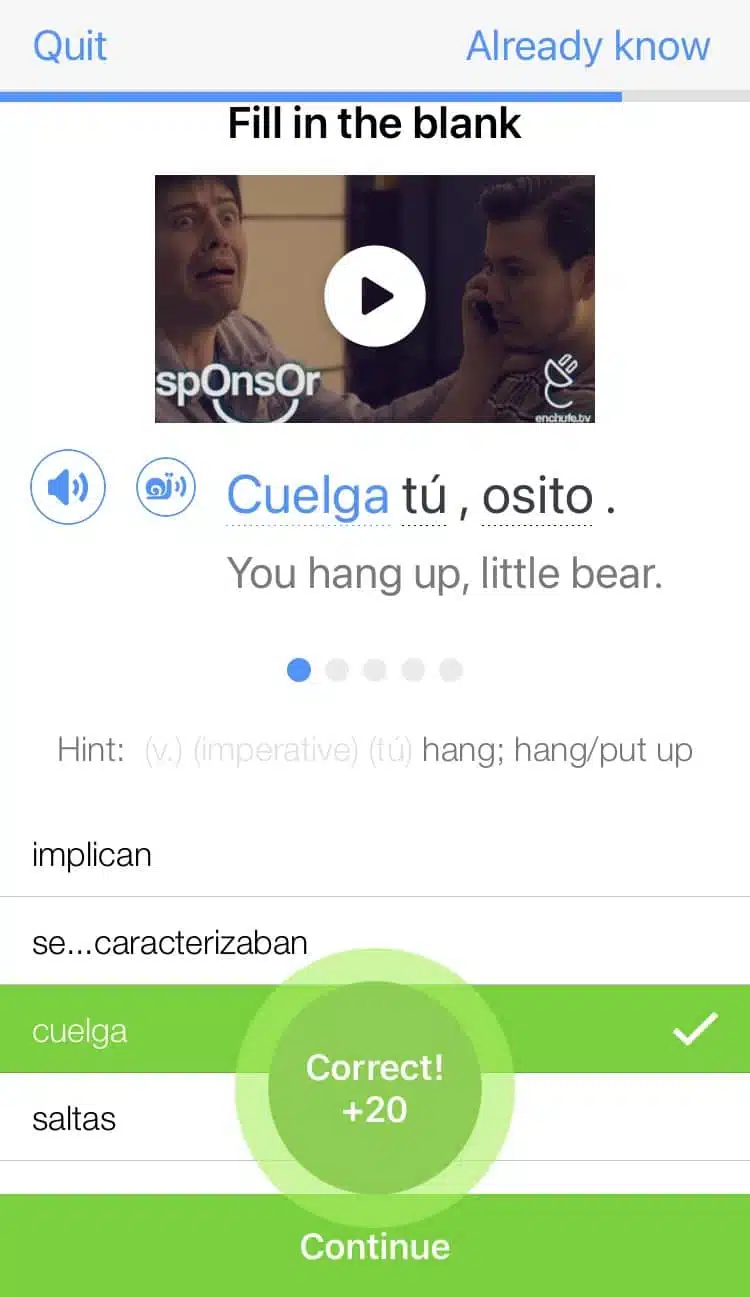

Learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU’s robust learning engine. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you’re on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you’re learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. Every learner has a truly personalized experience, even if they’re learning with the same video.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)