How to Read Mandarin Chinese: The Newbie’s No-stress Guide

Would you believe me if I said that reading Chinese, and learning Mandarin Chinese in general, is not as difficult as it seems? Chinese characters are not significantly more difficult than those in other writing systems.

You just need to understand the system to understand the characters.

In this guide, I’ll teach you how to read Mandarin Chinese and understand different Chinese characters using a range of useful methods.

Contents

- General Tips to Learn to Read Chinese

- Learn to Read Chinese with Pinyin

- How to Understand Chinese Character Meanings

- Using Chinese Phonetics

- Things That May Trip Up Beginning Readers

- Tips for Reading Unknown Characters

- How to Practice Chinese Reading

- 9 Common Phonetics and Radicals to Quickly Learn to Read Chinese

- 6 Common Phonetic Sounds in Chinese Characters

- Resources for Chinese Reading

- And One More Thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

General Tips to Learn to Read Chinese

When you are first starting out, learning to read Chinese feels like a daunting task. After all, you have probably heard the rumors that there are over 20,000 characters you will need to master, and that this is a completely different system from the alphabet you’re used to. Here are three helpful tips that can make it much easier to start.

Stick to either traditional or simplified

Don’t try to be Superman by mastering traditional and simplified Chinese at the same time. Many characters will be similar, but trying to master both at the beginning will hurt you rather than help you.

You may have heard that reading Chinese is about understanding the pictures they are representing. This is true for some traditional and simplified Chinese, but most of the time it’s not as simple as that. Sometimes it can help with memorizing and referencing characters, but unfortunately most characters will not represent objects in the physical world.

Start with the most common words

You have probably already done this with your Chinese speaking skills, but starting out with the most common words is important because you can begin spotting them right away: in your readings, in a menu or walking around Chinese streets.

This doesn’t mean you’ll be able to read entire newspapers or even menus with the most common words (because of how specific Chinese characters can be), but it’s a fantastic start!

Use mnemonics to memorize characters

Memory aids are key to making reading in Chinese easier when you are beginning. Remembering things in general, regardless of what language, is something that can be practiced.

When working with mnemonics, make sure they are are personal and catered towards yourself. Other people’s mnemonics can help, but only if they trigger something in your brain. For optimal results, focus each session on 5-10 words, and first get them into your short-term memory.

There are many free resources that can help you learn Chinese characters, which you should take advantage of immediately.

Learn to Read Chinese with Pinyin

The one aspect of Chinese that characters don’t cover is tones, which can greatly influence the meaning of your Chinese words. Learn Chinese tones before you learn Chinese characters.

Absolutely nothing within the character itself will remind you of the tone. Speaking with proper tones is a product of memorization.

The best way to learn to read Chinese tones properly is by using 拼音 (pīn yīn), which literally means “combine sounds.”

Pinyin is the romanized version of Chinese.

Beginner Chinese classes don’t tackle characters yet because they focus on getting accurate pronunciation and tones first. Chinese school children learn pinyin before they start learning characters, so if they need it, you and I do, too.

How to Understand Chinese Character Meanings

Even for beginners, it should soon become readily apparent that Chinese characters are not just “random drawings.” They actually follow a reasonably neat system by which characters can be easily split up into their component parts, making them much simpler to understand.

Radicals

The first and most important part of Chinese characters is what are called radicals. These are elements (usually found on the left hand side or underneath a character) that suggest the meaning based on broad categories.

A simple example of this is the wood radical based on the Chinese character for wood, 木 (mù).

This character can then be found as a radical in a number of wooden objects such as 桥 (qiáo) for “bridge” or 楼 (lóu) for “building.” Chinese is generally accepted to have 214 radicals, and these range from ones that convey a literal meaning to ones that convey a more vague feeling.

Are you with me so far? Okay, let’s move on.

Pictograms

Another important grouping within Chinese characters is pictograms. These are characters that are meant to look like the object or thing they represent. While the obvious similarities have been lost over thousands of years, with a little imagination and understanding of Chinese culture, you can start to recognize meanings. Some examples of these include 人 (rén) for “person;” 高 (gāo) for “tall,” represented as a tall pagoda; and 山 (shān) for “mountain.”

Ideograms

Similar to pictograms, ideograms are another old and somewhat confusing element of Chinese reading. These are characters that were pictographic representations of themes, rather than things, which have since been highly stylized.

A good example of these is the character 互 (hù) meaning “mutual,” which is a representation of two people holding hands. Such characters aren’t generally understandable on first viewing, but much easier to remember once the backstory is learned.

Pictophonetics

Okay, now the most common (and indeed most important!) group of characters for any Chinese reader are so-called pictophonetic characters.

These characters are made up of a radical element, which suggests what category of things (or actions) it belongs to, as well as a distinct phonetic component, which suggests how it should be pronounced.

Now, pay close attention, because learning these phonetic elements is the key to learning to read Chinese.

Using Chinese Phonetics

When many people start learning Mandarin Chinese, they are introduced to pictographic and ideographic characters and think that associating a character with a picture (and a meaning) is a good idea. Seems like an okay strategy, right? But watch out!

While this can be effective for the first 100-200 characters you might learn, such a strategy will inevitably fail. This is due to the fact that such characters make up only around 10% of the total Chinese characters, meaning that your picture associations will have to get progressively more outlandish and creative as your studies advance. Talk about crazy!

The basic theory of Chinese character phonetics

Luckily, there is a better way to read Chinese. Most of the Chinese language is written in pictophonetic characters, meaning that you simply need to learn all of the phonetic elements to be able to read significant portions of Chinese texts.

“Okay,” you’re thinking, “But what are these phonetic elements?”

Well, often these are difficult to tell apart from radicals, and unfortunately they are rarely taught officially by Chinese teachers who prefer rote learning of pronunciation and meaning. But once you start using at least a few hundred characters, patterns of pronunciation will emerge.

For example, almost all characters with 巴 (bā) in them—such as the final particle 吧 (ba), 把 (bǎ) meaning “to hold,” 爸 (bà) for “father” or “dad” and 疤 (bā) for “scar” or “scab”—will also be pronounced ba no matter what their meaning is, and no matter what additional radicals they have with them.

How to use phonetics to read fluently

So you know that these phonetic elements exist, but how do you use them to read? Well, to start with, check out this amazing spreadsheet, which lists almost all of the phonetic elements. I would suggest you learn as many of the phonetic sets in this document as possible, and then see if you can identify them in unknown pieces of text.

Often you’ll know the pinyin of a word far before you know its characters, and so by sounding the characters out using these phonetic sets, you’ll have a good chance of guessing their meanings.

Things That May Trip Up Beginning Readers

Okay, so now that you know how you should be reading Chinese characters, it’s also important to identify the common problems and mistakes that learners make when reading Chinese as a second language.

Avoid confusing similar characters

One of the most common mistakes that learners make is confusing two very similar characters. These include characters that are almost identical except for the radical.

Such character pairs—for example, 情 (qíng) for “feeling” or “emotion” and 清 (qīng) for “pure” or “just”—often are made more confusing by the fact that they have the same pronunciations.

Another kind of character similarity, such as that between 木 (mù) and 术 (shù) meaning “method” or “technique,” can occur when two characters very different in meaning and pronunciation have just a single stroke of difference between them.

Watch out for characters with alternate pronunciations

Another common error encountered by learners is caused by characters that have more than one possible pronunciation depending on their context. Some of the most common include 着, which can be pronounced as zhe as well as zhāo, and 重, which can be pronounced as zhòng or chóng in some circumstances.

But luckily, such multi-pronunciation characters are quite rare, and they can be easily learned and recognized.

Tips for Reading Unknown Characters

One final area of difficulty, which every learner without exception will encounter, is a text that’s just full of unknown characters. While it is impossible to guess the meaning of every character, there are some helpful hints that can be followed.

Nouns can be guessed by their radicals

With some understanding of Chinese grammar, it is reasonably easy to tell which Chinese words in a given sentence are nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs. For the nouns, at least, it is often possible to work out what kind of object an unknown word is, based on its radicals and knowledge of the content.

For instance, words with the heart radical 心 (xīn) generally refer to emotions or feelings, while something with the gold radical 金 (jīn) is likely some kind of metal or element.

Identifying toponyms and names

Some of the most hard-to-read characters come in the form of toponyms (place names). Often these can be completely unique characters—as in the case of the 峨 (é) in 峨眉山 (é méi shān), which is a mountain in Sichuan province—or be otherwise incredibly rare.

In many cases, like in the previous example, it is easy to tell this is a toponym by the fact that the character for a certain kind of place (such as a mountain, lake, river or valley) is used.

In other cases, for the transliteration of non-Chinese toponyms or the names of people, a very small group of characters is used consisting of basic phonetic sounds. Such characters are easy to identify and read, even if their actual meaning is unknown.

How to Practice Chinese Reading

Now that you know about how the Chinese character system works, along with its intricacies and difficulties, the next step is obvious. You just have to start practicing.

Read, read, read Chinese, and then read some more!

Obviously, you want to start off with easier texts before you jump into novels and such.

Begin with children’s stories and eventually transition into reading blog posts, short stories and news articles. Once you’re comfortable enough, you can read lengthier texts, such as novels.

Parallel texts are also extremely helpful for learners since they offer instant translations. However, I highly recommend that you read the Chinese text first, mark any unknown characters and try to deduce their meanings by using context, as well as the tips shared above. After that, you can compare them to the English text.

If bilingual texts are still too advanced for you, FluentU can help you ease into them. FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons. You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app. P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

9 Common Phonetics and Radicals to Quickly Learn to Read Chinese

1. 土 — Earth

The radical 土 stands alone to mean “earth” or “dirt.” The following examples will all be associated with “earth” in some form.

场 (chǎng) — field

地 (dì) — land

墙 (qiáng) — wall

塔 (tǎ) — tower

2. 金 — Metal

This radical derives from the character 金 (jīn), which means “metal” or “gold.” Examples of words that relate to the general category of “metal” are:

钱 (qián) — money

镜 (jìng) — mirror

钟 (zhōng) — gong, clock

针 (zhēn) — needle

铁 (tiě) — iron

3. 艹 — Plants

As you can tell from the following words, the similarity is in the top part, also known as the plant radical. The radical 艹 comes from the simple pictograph of two blades of grass hiding a snake.

草 (cǎo) — grass

花 (huā) — flower

茶 (chá) — tea

药 (yào) — medicine

4. 日 — Sun

Already mentioned earlier in the article, 日 is a pictograph that represents “sun.” When this radical appears in words, the word is usually associated with the weather, time or other sun-related concepts.

明 (míng) — clear (as in a clear day), also means “tomorrow”

晴 (qíng) — clear

时 (shí) — time

5. 水 — Water

Another pictograph, the left side of the following words looks like drops of water and is a simpler version of 水, or water.

河 (hé) — river

酒 (jiǔ) — wine

洗 (xǐ) — wash

6. 木 — Wood

The 木 part on the left and bottom of each word stands for “wood.” When you see this in a character, you will know it has some relation to wood or things that were originally made from wood.

桥 (qiáo) — bridge

桌 (zhuō) — table

树 (shù) — tree

7. 月 — Body part

You may recognize the 月 part as “moon” and wonder how that has anything to do with the body parts. It was originally 肉, which means “meat,” but has transformed over time to take on the current symbol.

脚 (jiǎo) — foot

腿 (tuǐ) — leg

肥 (féi) — fat

肝 (gān) — liver

8. 衤— Clothes

This radical is derived from 衣 which means “clothes.” You can see the similarity between the character and the radical.

补 (bǔ) — fabric

裙 (qún) — dress

衬 (chèn) — lining

衫 (shān) — shirt

9. 贝 — Money

贝 (bèi) means treasure, and this is why it’s the radical to represent money and wealth. 贝 also means “shell,” and if you know your Chinese history, you might have already made the connection that in ancient China, shells were used as a currency.

货 (huò) — merchandise

财 (cái) — wealth

贵 (guì) — expensive

6 Common Phonetic Sounds in Chinese Characters

This is where characters start getting tricky. The phonetic sounds that come from a character aren’t rules, but rather the sounds are seen as helpful recommendations that will sometimes work to your advantage. Not only will you be able to get the phonetics out of it, it will often also represent something related to the radical that’ll help determine the character’s meaning.

Other times, it can cause confusion and you will find yourself wrongly pronouncing words that look alike and mixing up meanings of the words. So just be careful when learning these to get the tones right, as a slight change in the character can be a completely different sound and meaning.

1. Bi

All the following words will be a combination of different radicals to the base 辟 (bì). Many characters will have either an origin or reference to royalty.

辟 (bì) — monarch, king

避 (bì) — avoid

壁 (bì) — wall

嬖 (bì) — favorite

2. Bian/Pain

The base word here is 扁 (biàn) which means “flat.” Though sometimes a long shot, many meaning of the characters with 扁 will stem from the general idea of “flat.”

遍 (biàn) — everywhere

编 (biàn) — compile, edit

篇 (piàn) — articles

骗 (piàn) — cheat

3. Jing

Not related in sound to 圣 (shèng), which means “saint,” there may be some reference in meaning to the word when adding various radicals to it.

经 (jīng) — past, after

径 (jìng) — path

刭 (jǐng) — cut throat

4. Jing/Qing

All the following words come from 青 (qīng) which means “green,” usually referencing nature. Some of the below words will have an obvious connection, while others may not be related at all besides in sound.

静 (jìng) — quiet

精 (jīng) — fine, perfect

睛 (jīng) — eye

晴 (qíng) — clear

请 (qǐng) — please

情 (qíng) — love

5. Kuai/Jue

夬 (guài) has transformed into a “kuài” sound. The original 夬 (guài) character means “parting” or “forked.”

快 (kuài) — fast

块 (kuài) — block

决 (jué) — decision

6. Man

The main character 曼 (màn) means “long, extended,” and similar to the above phonetic examples, you may be able to spot some connections with the following characters, while others will be a bigger stretch.

慢 (màn) — slow

漫 (màn) — flood

馒 (mán) — steamed bread

墁 (màn) — plaster

Resources for Chinese Reading

Here are some other online resources to practice your Chinese reading skills:

1. The Chairman’s Bao

The Chairman’s Bao publishes articles organized by HSK level, from 1-6. (It’s also an iOS and Android app.)

Each article comes with a list of keywords for that article and their meanings, as well as grammar points found in the article.If you double-click on a word in the article, the “live dictionary” on the side will give you the characters, pinyin and definition of the character.

The articles also feature audio tracks, so you can listen and read at the same time.

TCB features a weekly 成语 (chéng yǔ) or Chinese idiom in their email newsletter.

2. Wordswing

Wordswing offers plenty of Chinese text adventure games that are meant to get you more comfortable with reading in Chinese.

One of their games is Escape, which is a full-text RPG. Similar to other “escape the room” smartphone games, this involves finding clues and using discernment to make your way out of the situation. The difference, of course, is that it’s all in Chinese character text.

If there’s a character you don’t know or don’t remember, you can click on it and a sidebar will appear with the character, pinyin and meaning.

3. Chinese Reading Practice

This website provides readers with loads of stories for beginner, intermediate and advanced levels with information ranging from jokes to recipes.

As you read the stories, you can hover over a character you don’t know to get the pinyin and meaning.

Now you know how to read Mandarin Chinese! With these tips, reading Chinese is much more approachable. And with enough practice, you can be reading Chinese magazines, newspapers and other texts without a hitch!

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

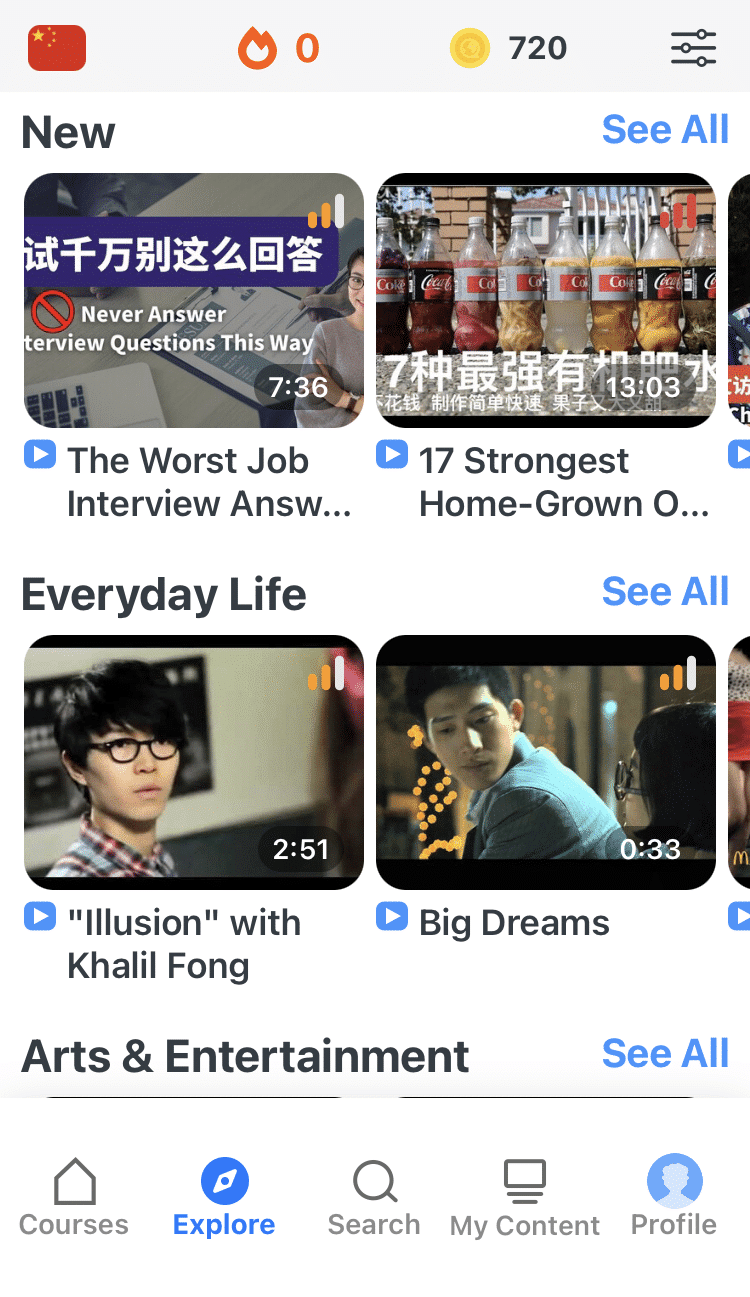

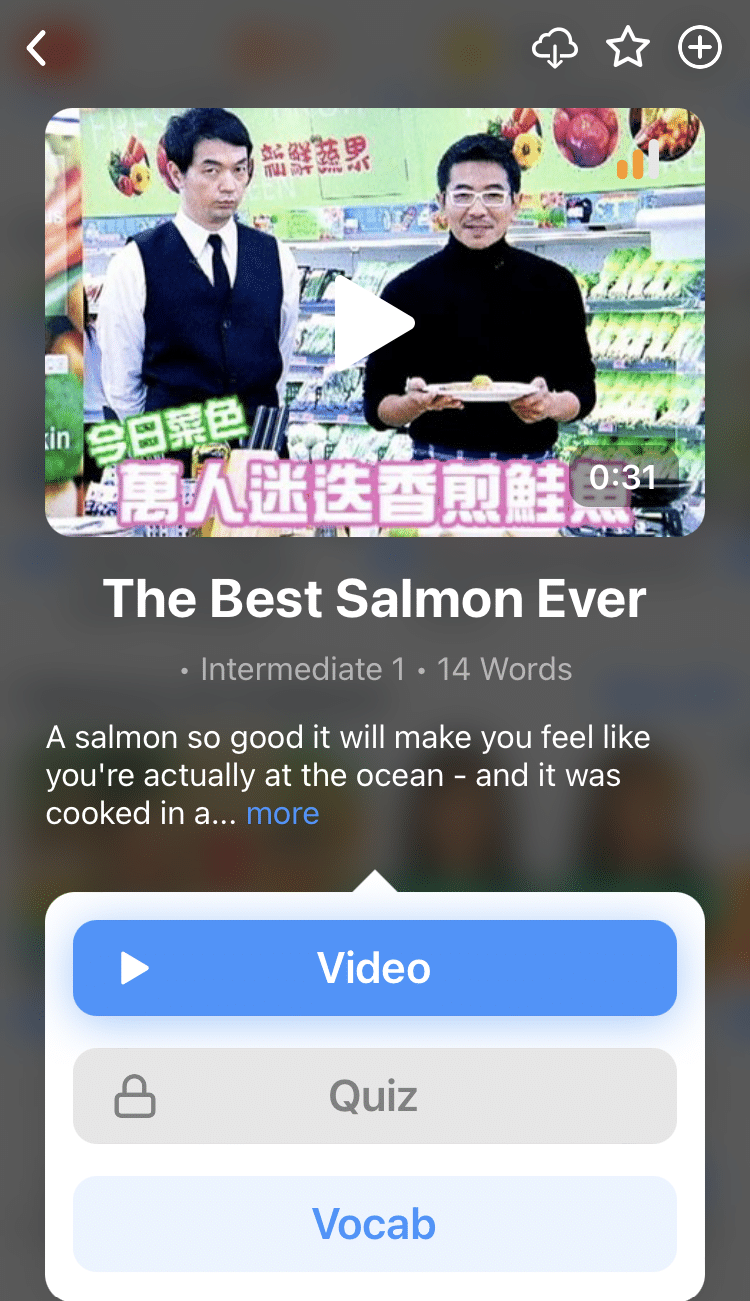

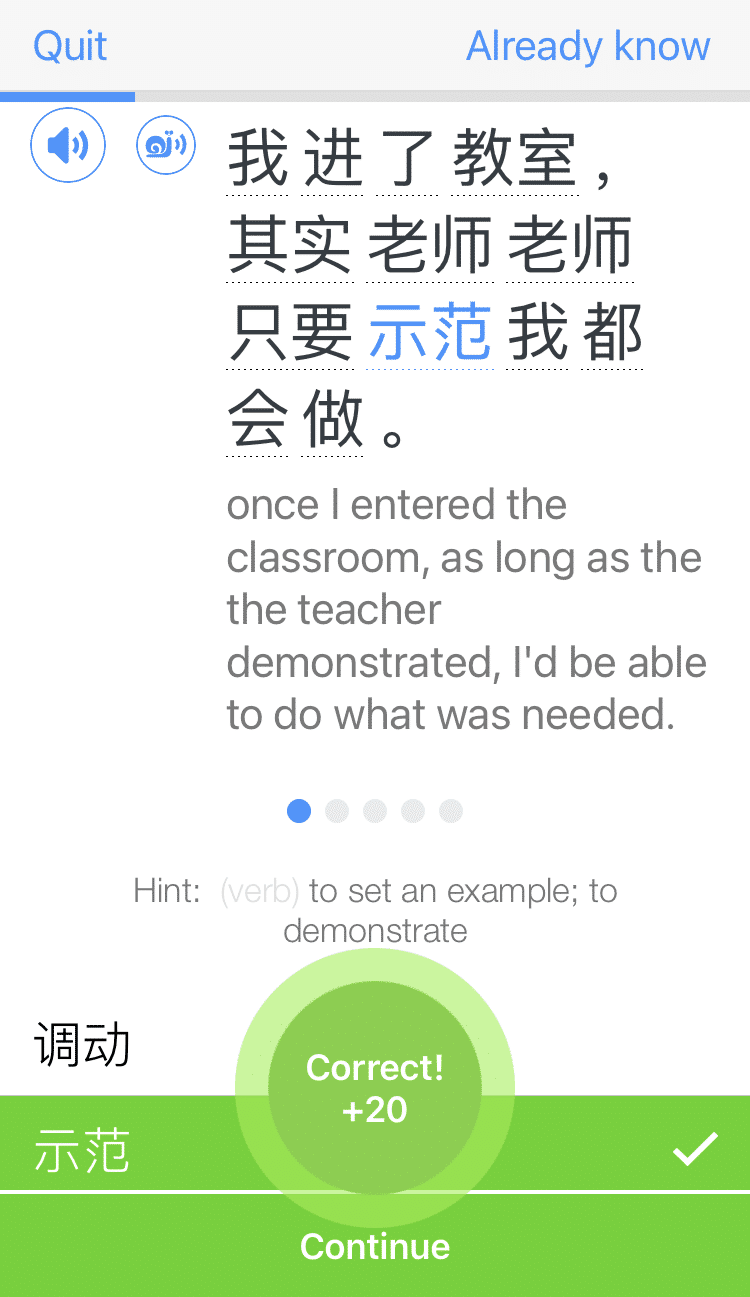

If you want to continue learning Chinese with interactive and authentic Chinese content, then you'll love FluentU.

FluentU naturally eases you into learning Chinese language. Native Chinese content comes within reach, and you'll learn Chinese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a wide range of contemporary videos—like dramas, TV shows, commercials and music videos.

FluentU brings these native Chinese videos within reach via interactive captions. You can tap on any word to instantly look it up. All words have carefully written definitions and examples that will help you understand how a word is used. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

FluentU's Learn Mode turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you're learning.

The best part is that FluentU always keeps track of your vocabulary. It customizes quizzes to focus on areas that need attention and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)And One More Thing...