The Easy Guide to French Sentence Structure

You don’t begin learning French by immediately building long, complex sentences. You start with words, phrases and grammar points then slowly start putting that all together. Once you grasp French sentence structure, it will be much easier to pick up on the rest of the language.

To make things easier, I’ve created this guide with everything you need to know about French word order, from the simplest sentences to more complex forms.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Basic French Sentence Structure

We have to start at the beginning with basic French sentence structure.

Like English, a French sentence will most often be formed with a subject, a verb and an object.

Unlike other romance languages, French does not drop the subject in most cases.

Also keep in mind that you will need to conjugate any verbs to match the subject, tense and mood.

In order to build even the simplest French sentence, you will need two or three elements.

Subject-verb Sentences

If a sentence uses an intransitive verb (a verb that indicates being or motion), such as aller (to go), courir (to run) or être (to be) it will be a Subject-Verb (SV) sentence:

Je suis. — I am.

Je in this sentence is the subject, and suis is the intransitive verb.

Since intransitive verbs do not need to take objects, the subject and verb is all that you need.

This is one of the simplest French sentences you can build.

Subject-verb-object Sentences

If a sentence uses a transitive verb, it will be a Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) sentence:

Tu as un chat. — You have a cat.

Tu in this sentence is the subject, as is the transitive verb and un chat is the object.

Remember that all nouns require an article in French, so even though this sentence has three parts, it actually has four words.

Types of Sentences

Statements

A statement is the most straightforward type of sentence. It will simply give you information and will typically follow the SVO structure although a SV sentence can also be a statement.

Here are some examples of French statements:

J’ai mangée une pomme. — I ate an apple.

Tu vas venir avec nous à la fête. — You’re going to come with us to the party.

Nous avons beaucoup de vin. — We have a lot of wine.

Commands

To give a command, you must use an imperative sentence, which can only be used with tu , nous or vous .

Tu and vous are used to give basic commands, while nous is inclusive and includes the idea of “Let’s.”

The biggest structural difference between imperative sentences and regular statements is that the subject may be implied.

In other words, you can simply drop the subject and leave just the conjugated verb:

Va! — Go!

Allons-y! — Let’s go!

Sois sage! — Be good!

Note that the imperative form is the only sentence structure that allows the subject to be dropped.

Exclamations

Just like in English, you can add emphasis to any statement by adding an exclamation point.

The difference between “let’s go” and “let’s go!” is that the exclamation point adds a whole new sense of excitement or urgency.

Je ne peux pas attendre! — I can’t wait!

Comme c’est mignon! — How cute!

Quel soulagement! — What a relief!

Questions

A question is an interrogative statement that is used to request some kind of information.

A question may elicit a yes/no response or be open-ended.

Allez-vous venir? — Are you coming?

Qu-est ce que c’est? — What is it?

Quand partons-nous? — When are we leaving?

You may have noticed in the examples above that there is a slight difference in the use of punctuation in sentences in English and French.

French punctuation is used differently in sentences. When written, a space is required both before and after certain punctuation marks, such as two-part punctuation marks (e.g., colons, question marks, exclamation points, etc.):

Comment allez-vous? (How are you?)

Bien, merci! (Good, thank you!)

Negative Sentences

In order to make any French sentence negative, you must surround a verb with two words.

In front of the verb, you will always have ne , although this is often omitted in spoken French.

Following the verb you will have the word which indicates the type of negation.

Some of these structures include:

Ne… pas — Not

Ne… rien — Nothing

Ne… jamais — Never

Ne… personne — Nobody

Ne… plus — Not anymore

Ne… aucun — None

Examples of these are:

Je ne suis pas contente. — I am not happy.

Tu ne sais rien de ça? — You don’t know anything about that?

Elle ne boit jamais d’alcool. — She never drinks alcohol.

Il n’aime personne. — He doesn’t like anybody.

Nous n’allons plus à l’église. — We don’t go to church anymore.

Elles n’aiment aucun homme. — They don’t like any men.

Structuring Questions in French

There are three basic question forms in French, each with its own rules.

Inversion Questions

One of the easiest sorts of questions to ask in French is called an inversion question. It is so named because of the way in which the question is formed: by inverting the subject and the verb of the sentence:

As-tu un chat? — Do you have a cat?

The question form of the sentence puts the verb before the subject, with a hyphen to show that the two have been inverted. These questions can only be answered by yes or no.

Question Tags in French

The basic question tag in French is “Est-ce que.” It marks the beginning of a yes/no question, much in the same way that inversion does.

The difference here is that the sentence that follows will retain the basic French sentence structure.

Est-ce que tu veux venir? — Do you want to come?

Qu’est-ce que is a variation on this question tag. By putting que or “what” at the beginning, you can ask a question requiring a more elaborate answer.

Qu’est-ce que tu veux manger? — What do you want to eat?

Question Words in French

If you want to ask an even wider variety of questions, you can use French question words alongside the est-ce que structure.

French question words include:

These words are simply tacked on to the beginning of an est-ce que question in order to have the desired meaning:

Qui est-ce que tu appelles? — Who are you calling?

Quand est-ce qu’on part? — When are we leaving?

Où est-ce qu’on va? — Where are we going?

Pourquoi est-ce que tu pleures? — Why are you crying?

Comment est-ce que ça marche? — How does it work?

Questions with Intonation

Sometimes you may hear someone ask a question in French that does not invert the structure, use a tag or a question word.

So how do you know that it’s a question? It’s because of intonation!

In spoken French, you can make almost any sentence a question simply by raising your voice a little bit at the end of the sentence:

On va voir un film? — Should we go see a movie?

Tu veux manger un truc? — Want to get something to eat?

This sort of structure is acceptable in casual, spoken French, but not in written or formal French.

If you want to sound like a native, you’ll have to learn to pick up on these various sentence structures and incorporate them into your casual French.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Pronoun Placement in French Sentences

One of the most difficult French sentence structure ideas for French language learners to grasp is undoubtedly where to put the pronouns.

The reality is that it is actually pretty simple once you know the difference between a direct and indirect object.

A direct object is the object of a transitive verb, while an indirect object is not. For example:

I gave him the ball.

The ball is the direct object. You know because the sentence cannot exist without it. Him is the indirect object.

Now let’s look at this in French:

J’ai donné le ballon à Jacques. — I gave Jacques the ball.

In French, if you need to replace these words with pronouns, the sentence would be written like this:

Je le lui ai donné. — I gave it to him.

Object pronouns in French are preposed, so they appear before the verb. Direct object pronouns such as le (it; him), la (it; her) and les (them) always appear before the indirect object pronouns lui (to him; to her) and leur (to them).

This rule is also applicable for more complex pronoun sentences.

When to Use En and Y

En and y are similar to direct and indirect objects in that they replace an understood phrase (meaning you don’t have to repeat the same few words over and over).

En replaces phrases beginning with a partitive article (de, du, de la, d’), which is used to, in essence, denote an indeterminate “part” of something, like in du chocolat (some chocolate).

En may also replace most phrases beginning with some form of de, such as when it is employed with an infinitive.

“J’ai décidé de passer mes vacances en France” (I decided to spend my vacation in France) could become simply:

J’en ai décidé. — I have decided on it.

Finally, en stands in for phrases expressing number or quantity.

For instance, if a specific number is given, as in “Il a lu cinq livres ce mois” (He read five books this month), then we replace the noun with en and retain the number itself at the end of the sentence:

Il en a lu cinq ce mois. — He read five of them this month.

Y, on the other hand, will replace most phrases beginning with à, au or aux and phrases specifying location.

For example, “J’habite à Chicago depuis six mois” (I have lived in Chicago for six months) might become:

J’y habite depuis six mois. — I have lived there for six months.

As you have probably noticed, both en and y go before the verb, just like direct and indirect object pronouns do.

If we were to use en and y in the same sentence, y would go first.

I know this is a lot to remember, and it understandably takes time and practice to get it down. Even then, review is always helpful. A good first step (or refresher!) is this short quiz that tests use of en and y, as well as some of the object pronouns we covered earlier.

How to Use Adjectives

French adjectives can seem kind of weird because they usually go after the noun they modify, not before. To give a simple example, one would say une maison bleue (a blue house).

However, there are exceptions to this.

Fortunately, we do have a handy acronym to help remember what these exceptions are, so don’t panic yet! This acronym is BAGS:

- Beauty. Words like joli (pretty) and beau (handsome): un joli tableau (a pretty painting)

- Age. Words such as vieux (old) and jeune (young): un jeune homme (a young man)

- Goodness. Words such as bon (good) and mauvais (bad): un bon livre (a good book)

- Size. Words such as petit (small) and grand (big): une grande ville (a big city)

Since an adjective may come either before or after the noun, it is possible for a noun to have an adjective both before and after it, such as in ma nouvelle robe rouge (my new red dress). Since “new” describe age, it precedes the noun.

How to Use Adverbs

Adverbs describe how something is done. Just as adjectives modify nouns, adverbs modify verbs, adjectives or other adverbs.

J’ai marché lentement au parc. — I slowly walked to the park.

As in the sentence above, adverbs usually go after the verb (or other word) they modify.

But, as always, there are exceptions! Some adverbs go at the beginning of the sentence. These are generally adverbs that describe time or affect the sentence as a whole.

Hier, j’ai fait le linge. — Yesterday, I did the laundry.

Heureusement, elle a reçu une bonne note. — Fortunately, she got a good grade.

Some short, common adverbs like bien (well) and jamais (never), when used with the passé composé (perfect tense), actually go between the participe passé (past participle) and verbe auxiliare (auxiliary verb):

Il était un bon étudiant parce qu’il a souvent étudié. — He was a good student because he studied often.

To get some practice with all of these patterns, try out this quiz, which tests where to properly place adverbs in a sentence.

Sentence structure is an essential part of the French language, and with practice, you’ll soon find it easier to form sentences and speak the language with confidence.

Bonne chance! (Good luck!)

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

If you like learning French at your own pace and from the comfort of your device, I have to tell you about FluentU.

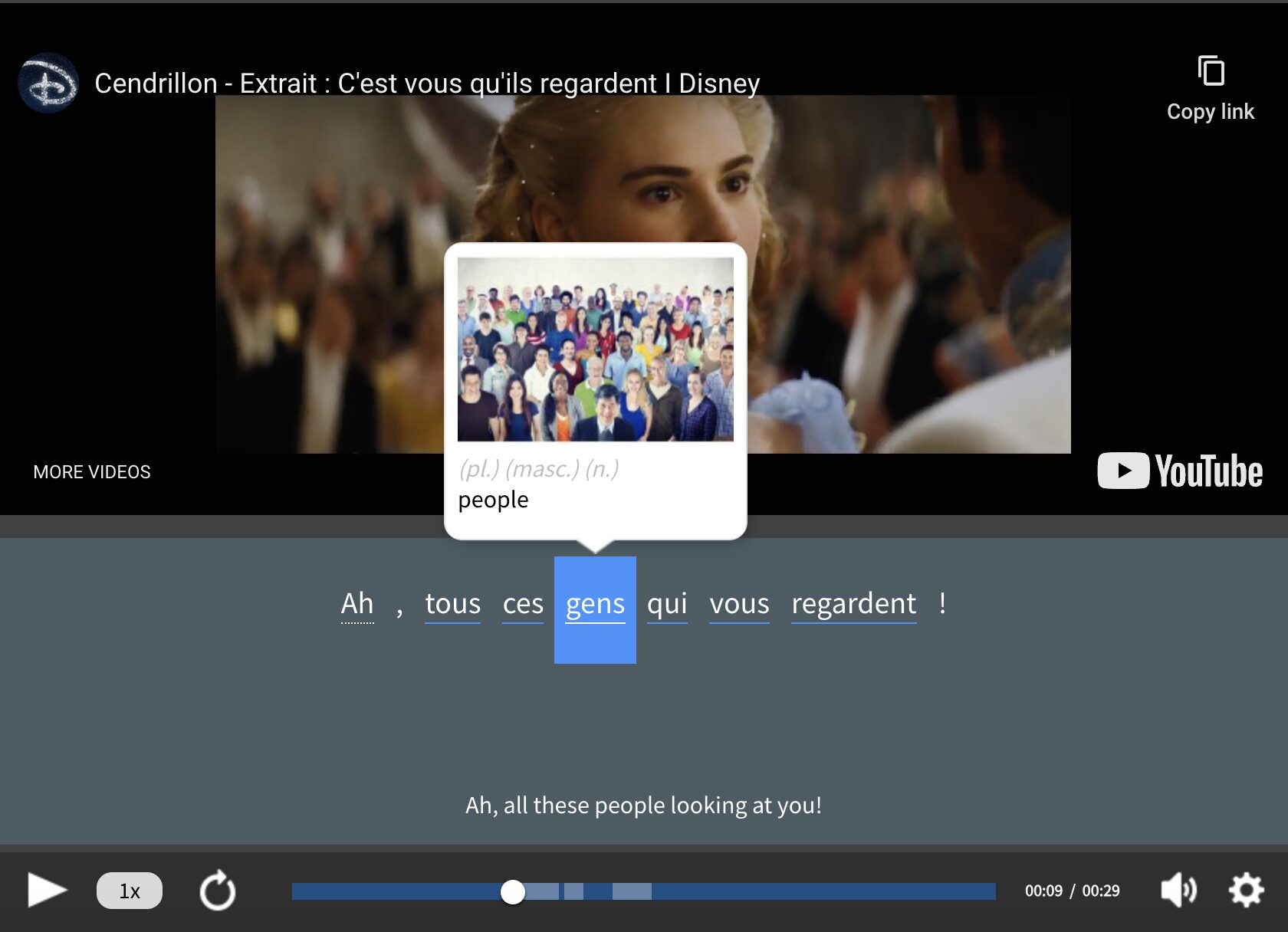

FluentU makes it easier (and way more fun) to learn French by making real content like movies and series accessible to learners. You can check out FluentU's curated video library, or bring our learning tools directly to Netflix or YouTube with the FluentU Chrome extension.

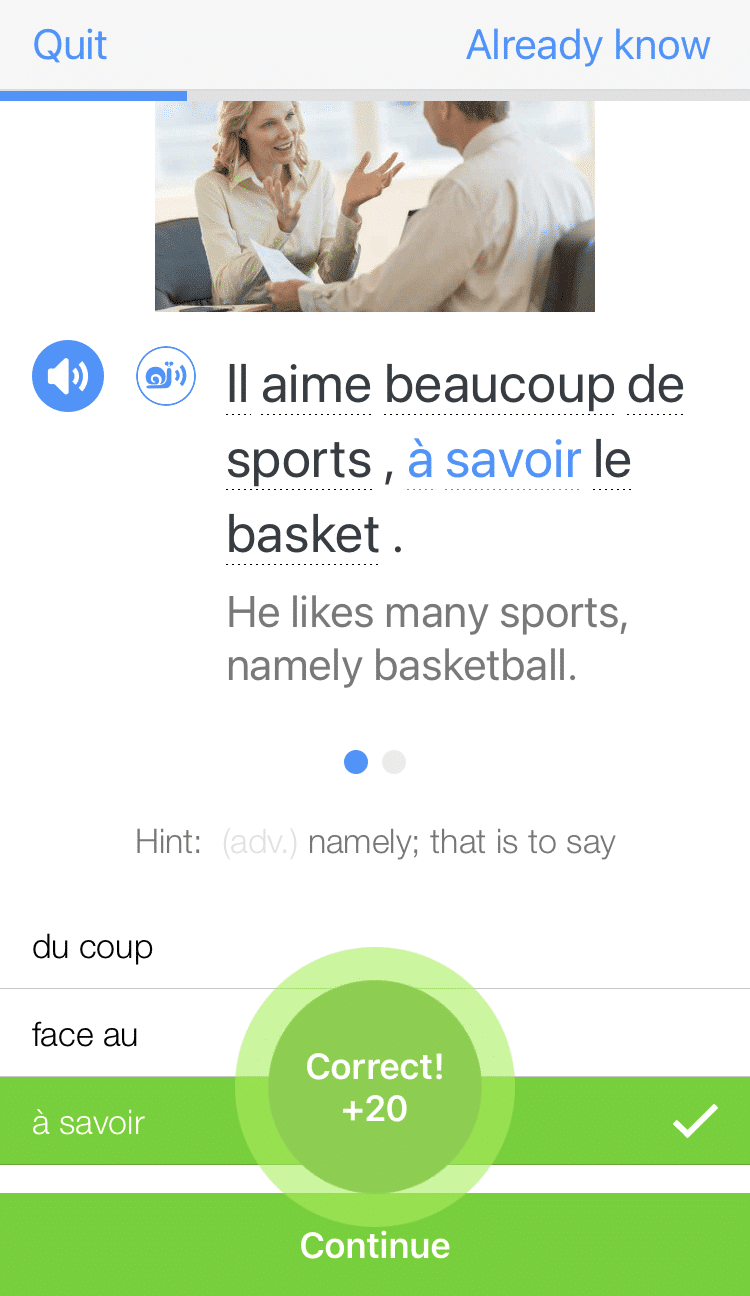

One of the features I find most helpful is the interactive captions—you can tap on any word to see its meaning, an image, pronunciation, and other examples from different contexts. It’s a great way to pick up French vocab without having to pause and look things up separately.

FluentU also helps reinforce what you’ve learned with personalized quizzes. You can swipe through extra examples and complete engaging exercises that adapt to your progress. You'll get extra practice with the words you find more challenging and even be reminded you when it’s time to review!

You can use FluentU on your computer, tablet, or phone with our app for Apple or Android devices. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)