How to Use Prepositions in German

Maybe you have been struggling with your mits and aufs. Maybe prepositions are going to be the subject of your next class and you simply want a head start.

Whatever the case, you’ve come to the right place. I’ll have you knitting prepositions into your German sentences beautifully by the end of this.

Contents

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

How Prepositions Work in German

Prepositions are words that link a noun to the rest of the sentence. They usually tell you about time, place and direction.

Examples of English prepositions include on, out, under, from, with, about and until, but there are many more. They are those little words that you don’t even notice you’re using, but which completely change the meaning of the sentence.

In German, using prepositions is more complicated because of German’s case system. German prepositions affect the case of the noun that follows them.

There are four German cases: nominative, accusative, dative and genitive. Most German sentences include at least one case.

- The nominative case is the subject of the sentence.

- The accusative case is typically used for the direct object of the sentence.

- The dative case usually occurs as the indirect object of a sentence.

- The genitive case is typically used to show possession.

The great thing about prepositions and the cases is that it stops you from having to worry about what function the noun in playing in the clause (Is it a direct object? An indirect object? etc.). Instead, all you have to do is look at the preposition.

For example, if you want to say that you’re going somewhere with your parents, you automatically know that Eltern (parents) must be in dative because it’s preceded by mit (with).

But we’ll get to that in due course. For now, let’s look at the different types of prepositions you might encounter.

German Prepositions That Take the Accusative

There are many prepositions which are always followed by the accusative case. So it doesn’t matter where it comes in a sentence, the noun directly following these prepositions are automatically in the accusative.

A list of these would look a lot like this:

bis until, up to, by durch through, across entlang along für for gegen against, towards ohne without um around, about,

at (when talking about time)

German Prepositions That Take the Dative

Alongside prepositions that take the accusative, there are also those which only take the dative. These work exactly the same way as accusative prepositions, but (obviously) they are followed by the dative case.

These include:

ab from (referring to time) laut according to aus out of, from mit with außer except for, apart from nach after, to (referring to direction),

according to bei by, at, in view of seit for, since dank thanks to

(can also be followed by the genitive) von from, of entgegen contrary to zu to gegenüber opposite zufolge according to

(follows the noun) gemäß according to

It can be hard work remembering which prepositions take which case, but there are ways of making it stick. It’s best to learn which case a preposition takes when you’re in the process of learning the word.

So, however you choose to learn your vocabulary, make sure you write the corresponding case on those flashcards or posters, and don’t forget to chant the case alongside the preposition as you’re waiting for the bus.

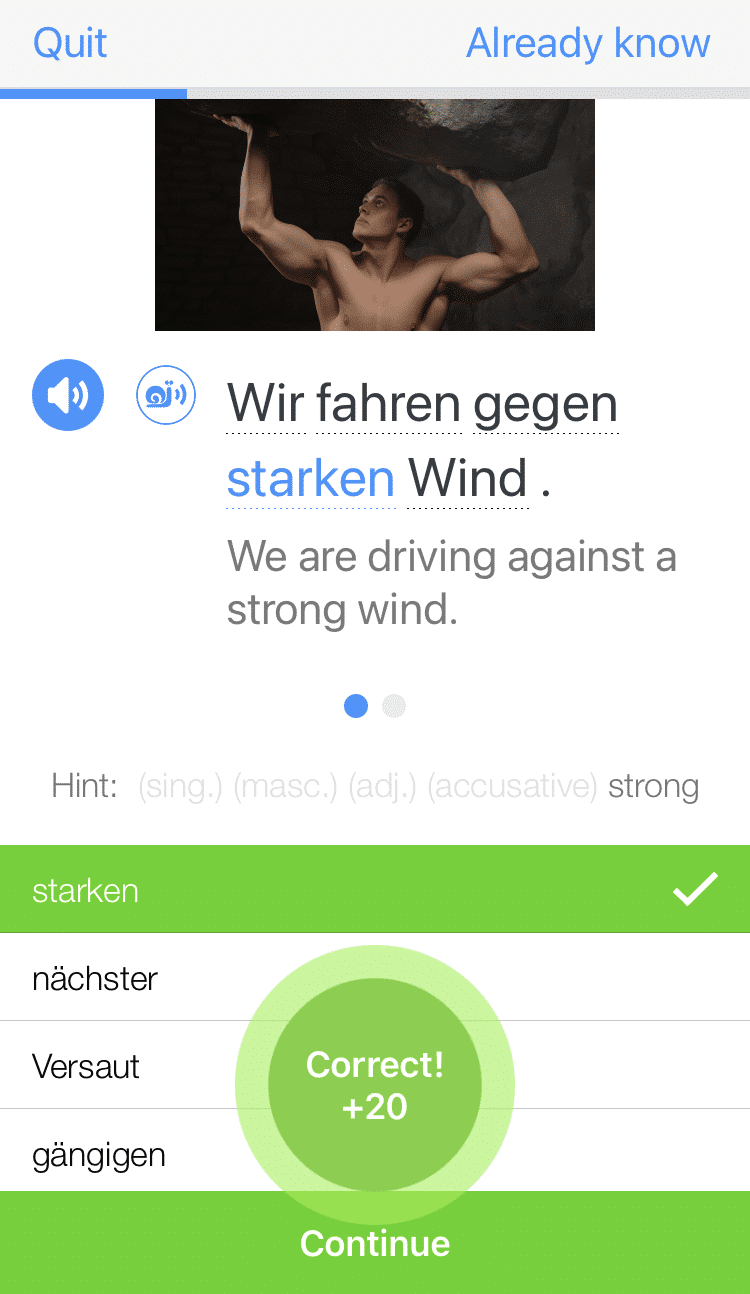

For a more portable option, use a flashcard app to keep track of and review all your new vocab. An app like FluentU will take this one step further and let you make flashcard decks with multimedia.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Learning phrases with prepositions in them is another excellent way to learn which case they take. You always have a phrase to refer to if you can’t remember off the top of your head.

So for example, you might learn the phrase entgegen allen Erwartungen (contrary to all expectations). From the n in allen, you will always know that entgegen takes the dative (if it were accusative if would read alle).

Two-case German Prepositions

Now here’s where things get interesting! Wechselpräpositionen (two-case prepositions) are prepositions that can take either the dative or the accusative (Great!). Except, you can’t use them interchangeably (Oh…). But fear not: There’s a rule. And once you’ve got that rule down, you’ll be fine.

The rule is all about what you’re trying to say, and it has to do with direction and position:

If you’re trying to express direction or change, use the accusative.

If you’re trying to state a static position, or that something is staying the same, use the dative.

It’s easier with examples. Take the following sentence:

Ich hänge das Bild an die Wand. (I hang the picture on the wall).

Here, we are talking about a movement. I’m describing myself hanging up the picture, moving it onto the wall. Therefore, we have a direction, so an takes the accusative: an die Wand.

On the other hand, have a look at this next sentence:

Das Bild hängt an der Wand. (The picture is hanging on the wall.)

This one expresses a static position: It tells the reader where the picture is, and implies no direction. In this case, the an takes the dative: an der Wand.

Watch out for examples where there is movement, but no direction or change in state:

Wir gehen im Park spazieren. (We’re walking in the park.)

Although we’re describing movement, the movement is confined within the park, so there is no direction or change of state, so in takes the dative.

If we were to describe ourselves going to the park, however:

Wir gehen in den Park. (We’re going to the park.)

Here we’re going into the park, presumably from somewhere else. As there’s a direction and change of state, in takes the accusative here.

Make sense? Here are some more examples, just to make sure.

Directional:

Ich lege das Buch auf den Tisch.

(I place the book on the table.)

Ich setze mich neben meine Frau.

(I sit down next to my wife)

Heute gehen wir in die Stadt.

(Today, we are going to town.)

Positional:

Das Buch liegt auf dem Tisch.

(The book is on the table.)

Ich sitze neben meiner Frau.

(I am sitting next to my wife.)

Das Haus liegt in der Stadt.

(The house is in town.)

It’s also important to note examples where no literal movement is being described, but rather a change in state:

Die Raupe hat sich in einen Schmetterling verwandelt. (The caterpillar transformed into a butterfly.)

Here, after the preposition in, you need to use the accusative case, as you are describing something transforming into something else. Change, ergo dative!

German Prepositions That Take the Genitive

Okay, I lied. There aren’t just three categories of prepositions. There’s actually a fourth: prepositions that take the genitive. But these are rarer, and there are only a couple that are really important to know.

And I’ll let you in on a little secret, too: Many Germans don’t use the genitive with these prepositions when they’re speaking. They use the dative instead. But if you have exams to take or academic papers to write, we’d advise using the genitive when you can.

Here’s a handy list of genitive prepositions:

anstatt

statt instead of außerhalb

innerhalb

oberhalb

unterhalb outside/inside/

above/below diesseits

jenseits

beiderseits

on this side of/on the other side of/

on either side of trotz in spite of unweit not far from während during wegen because of

Notice how all the prepositions ending in -halb or -seits take the genitive.

Also, as a general rule, prepositions with an English translation which includes the word “to” take the dative (thanks to, according to…), whereas most of those that include the word “of” take the genitive case (in spite of, because of…).

Of course, that’s not a hard and fast rule, but it’s worth knowing for those times when you are without a dictionary and need to make an educated guess.

German Verbs That Take Prepositions

The last big thing to learn about prepositions is their relationship with verbs. And it turns out, verbs and prepositions tend to get kind of cozy with one another. Just as in English, there are specific verbs that are always followed by specific prepositions.

Consider, for example, the verb “to fall in love.” In English, you fall in love with someone (if you’re lucky…or indeed, unlucky!). You never fall in love “about” somebody or fall in love “for” somebody.

It’s the same in German. Except that unfortunately, the preposition/verb combinations don’t always match up. In German, you fall in love “in” someone:

Ich habe mich in sie verliebt. (I have fallen in love with her).

I know, I know—this sounds like a nightmare: How on earth are you meant to know which prepositions to use? Well, I’m not going to lie. It’s hard. But there are certain things you can do to lessen the struggle.

- Learn the prepositions (and the cases that they take) at the same time as learning the verb. Learn the whole thing as a unit: instead of learning sich verlieben (to fall in love), learn sich verlieben in (+ accusative). That way it will stick in your head.

- Learn examples. Everyone is always going on about learning examples (myself included), but this is probably the most useful time to do it. When I was school, I learned a load of verb/preposition combinations by sticking signs up all over my parents’ house. On the inside of back door it read Achten Sie auf das Glatteis (beware of the sheet ice), with a big warning sign above it.

Here’s a handy list of verb/preposition combinations to get you started.

3 Ways to Use German Prepositions Like a Native

1. Contractions

So, you’ve got the basics down. Now to make yourself sound like a native. And one of the easiest things to do to achieve that aim? Use preposition contractions.

And that’s not just in spoken language; these can be written, too. It’s like “don’t” and “can’t” in English, but even more common (and they don’t use apostrophes for this kind of contraction).

Here’s a list of the most common German contractions:

an

+ das ans in

+ dem im an

+ dem am von

+ dem vom auf

+ das aufs zu

+ dem zum bei

+ dem beim zu

+ der zur in

+ das ins

2. Prepositional adverbs

Sounds scary, doesn’t it? But actually it’s really simple. So simple, that lots of people start using them without even noticing they’re doing it. In fact, I didn’t even know what they were called until I just looked it up.

Prepositional adverbs are formed by taking a preposition and putting the prefix da- (or dar- if the preposition begins with a vowel) on the beginning. So auf becomes darauf , von becomes davon , and so on. They are used to refer back to something you’ve just mentioned, and the Germans use them all the time.

Again, it’s probably easiest to understand using examples.

Ich fahre morgen nach Berlin, aber meine Mutter weiß nichts davon. (Tomorrow, I’m going to Berlin, but my mother doesn’t know anything about it.)

Er hat einen neuen Job und er freut sich sehr darüber.

(He has a new job and he’s really pleased about it.)

The da + preposition word can also come before the thing you’re referring to, as in the following examples:

Ich denke darüber nach, mein Auto zu verkaufen.

(I’m thinking about selling my car.)

Sie träumt davon, eines Tages Schauspielerin zu werden. (She dreams about becoming an actress one day.)

This happens when you’re using a verb (or verbal phrase) which is usually used with a preposition, but you don’t have a noun to follow the preposition. Many verbs don’t really make sense in German without their prepositions (see the list above), so you have to find a way to keep the preposition.

For example, the first sentence uses the verbal phrase über etwas ( + Akkusativ ) nachdenken (to think about something).

In this case, it is simple: The noun that follows über is put in the accusative case. In the example, however, the thing that I am thinking about is not a noun, but a whole clause with a verb—selling my car. Because you cannot put an entire clause in the accusative case, you have to put in a little da-.

It may seem a little weird at first, but after a while it becomes completely natural. In German, the sentences are very well-ordered. Everything must be tied up and neat.

Therefore you can’t leave a preposition hanging without a noun, so the da- is just a way of tidying up. If you think about a literal translation of that example sentence, things may become a little clearer: I am thinking about (the idea of) selling my car.

3. Phrases with prepositions

And one final tip for the keen beans: There are loads of great idiomatic phrases that use prepositions which are really handy in everyday speech.

Learn these, and you’ll have the whole prepositions thing down. And you’ll have your German business partners/school exchange partners/hotel staff/friends eating out of your hands.

Here are a few to get you started:

Es kommt darauf an. It depends. Ich bin damit einverstanden. I agree. Ich halte nicht viel davon. I don't think much of it. Beim besten Willen nicht By no stretch of the imagination Hör auf damit! Cut it out! Keine Spur davon No sign of it mit Waschbrettbauch Ripped, muscly

Literally: with a washboard stomach

So there you have it, German prepositions in a nutshell.

They may not be the easiest thing to learn, but they are seriously useful. And if you do everything we’ve suggested here, you’ll soon be laughing and thinking, “What did I even find so complicated?”

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

And One More Thing...

Want to know the key to learning German effectively?

It's using the right content and tools, like FluentU has to offer! Browse hundreds of videos, take endless quizzes and master the German language faster than you've ever imagine!

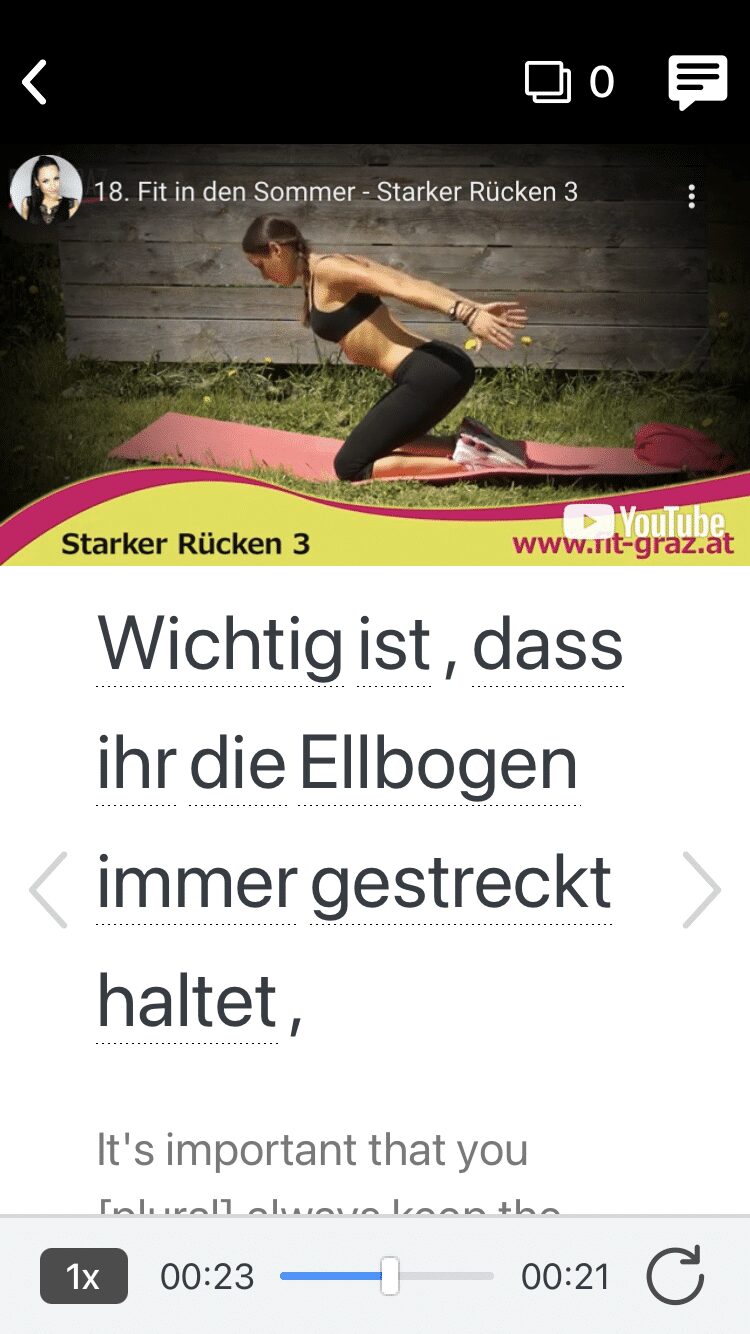

Watching a fun video, but having trouble understanding it? FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive subtitles.

You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don't know, you can add it to a vocabulary list.

And FluentU isn't just for watching videos. It's a complete platform for learning. It's designed to effectively teach you all the vocabulary from any video. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you're on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you're learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)